TAIPEI, Taiwan — The name on his government ID when he was growing up — and how his classmates, teachers and baseball teammates knew him — was Chu Li-jen.

At home, however, he was always Giljegiljaw Kungkuan, or “Giyaw” for short, the Indigenous name bestowed on him by his grandmother.

By the time he was a teenager, he wanted to go by his Indigenous name all the time, as a matter of pride. But his parents worried that abandoning his Chinese name would only cause him trouble in a Chinese-dominated society.

In 2019, he finally made it his legal name with the Taiwanese government after Cleveland’s MLB franchise — grappling with its own name issues — invited him to spring training. He wanted to ensure that come the next season, the letters emblazoned on his jersey would read: “GILJEGILJAW.”

Taiwan’s nationalist party is looking to the purported great-grandson of Chiang Kai-shek to refurbish its image.

“Honestly I didn’t think too much about it,” said Giljegiljaw, 29. “I just had the simple notion that I wanted to carry my name on my back, on my jersey.”

For the 585,000 members of the 16 Indigenous nations recognized in Taiwan, such decisions can be complex.

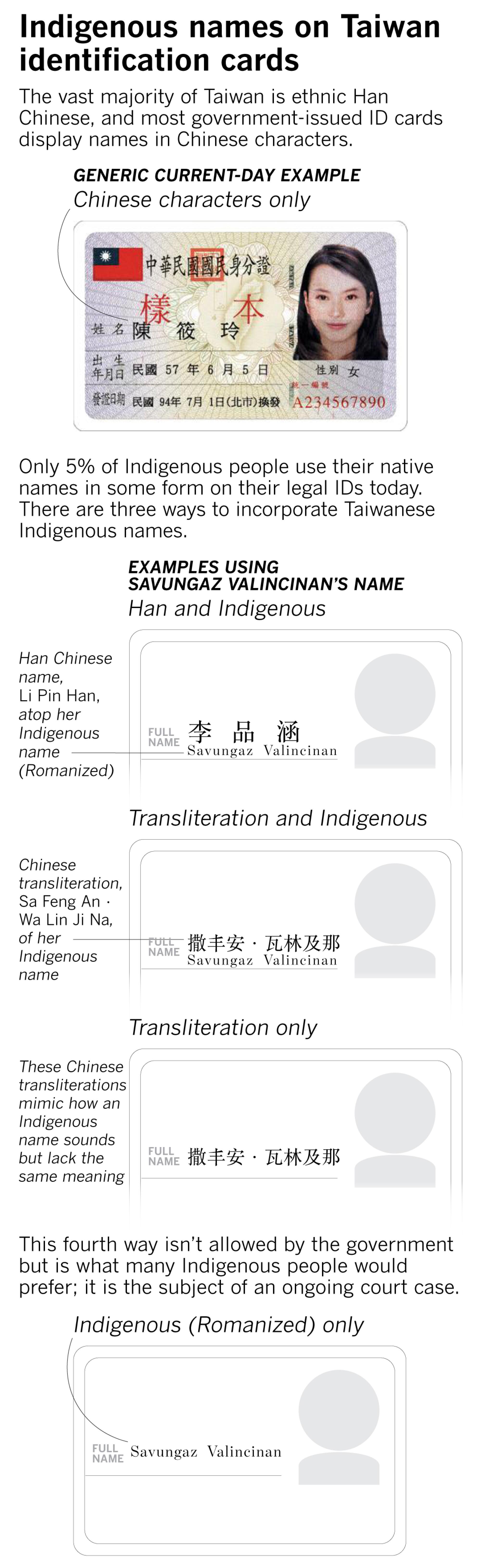

As relations with China have soured, more Taiwanese are embracing the island’s Indigenous history as they seek a national identity distinct from mainland China, where more than 95% of the island’s population can trace its roots. Yet, dissuaded by bureaucratic hurdles and fears of discrimination, only about 5% of Indigenous people use their native names in some form on their legal IDs today.

Ethnic Han Chinese began relocating to the island in large numbers during the 17th century. Migration surged again after the second World War when the Chinese Nationalist Party, better known as the Kuomintang or KMT, took control of the island in 1945.

For the record:

7:42 p.m. May 10, 2023An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that about 2.5% of the island’s population is of Austronesian descent. That figure is the proportion officially recognized by the government as Indigenous, a designation based on documented family lineage. It is unclear how many more Taiwanese have Austronesian ancestors who inhabited the island before the arrival of Chinese, Japanese and Dutch settlers.

Only about 2.5% of the population is recognized by the government as Indigenous, a designation based on documented family lineage. It is unclear how many more Taiwanese also have Austronesian ancestors who inhabited the island before the arrival of Japanese, Chinese and Dutch settlers in the early 1600s.

To promote a national Chinese identity, the KMT forced Indigenous people to use Han Chinese names in place of their own customs, which vary by Indigenous tribe but often include passing down a parent name or clan name instead of the surname familiar to Chinese or English names.

“Our constitution says we are China, but that’s the history that the KMT brought over,” said Ljegay Qeludu, a 32-year-old Indigenous graduate student at National Chengchi University. “That history has nothing to do with mine.”

Formerly registered as Chiu Tzu-chieh, he decided to officially go by his Paiwan name in 2015, spending hours at various government offices revising legal documents over the course of a week.

Using his Indigenous name to book a dinner reservation has often resulted in confusion, he said. And on trips to Japan and New Zealand, he’s had to spend additional time at immigration, explaining why his name is twice as long as most other Taiwanese travelers. Still, he said, the minor headaches have been worth expressing his Indigenous identity.

“It’s really annoying,” he said. “But I think I can also use these experiences to let everyone know more about Taiwan.”

Yes, I am Taiwanese American, but I regret to inform you that I will not be taking a side on whether House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was right to visit Taiwan last week.

Few are willing to spend time amending credentials like IDs, driving licenses, health insurance and bank accounts. And those who adopt the often longer names can draw unwanted questions or social prejudice, some say.

In the nearly three decades since such changes became legal, hundreds of Indigenous people have returned to their Han Chinese names because of discrimination or stereotypes, said Wang Ya-ping, an associate professor of ethnic studies at National Chengchi University.

Another barrier is how those names are written on official documents. Indigenous people are allowed to use either a traditional Han Chinese name or a Chinese transliteration of their native name, which many complain sounds clunky and imprecise. They can also include what is known in Taiwan as the “Romanization” of the Indigenous name, which means that it is written out phonetically with the Latin letters used in English and other Western languages — the same way Giljegiljaw’s name was displayed on his Cleveland uniform.

Now some are fighting to drop the Chinese characters altogether.

In 2021, a group of Indigenous activists sought approval from local government agencies to write their names only in Latin letters, which they argued were better suited to the pronunciation and preservation of Indigenous languages passed down orally. The Ministry of the Interior rejected the petition that year on the basis that most Taiwanese people wouldn’t be able to read the names.

This year, the ministry said it would follow the direction of the executive branch of Taiwan’s government, which said it was considering the issue and held a meeting last August to discuss using Indigenous languages to register names.

One of the activists, Savungaz Valincinan, still remembers slights she suffered because of Indigenous stereotypes growing up with a Han Chinese father and a mother from Taiwan’s Bunun tribe.

A schoolteacher, she recalled, commented that even though she was Indigenous, she didn’t look like she could run very fast. An Indigenous friend said Savungaz didn’t seem like she could hold her alcohol like other Bunun people — that night she drank herself sick to prove him wrong.

“It’s not because I want to choose between my mother and my father,” the 36-year-old said of her decision to change her name. “Growing up, I spent so much time becoming a model Han Chinese person. But there wasn’t enough time to learn about my mother’s culture, or to become someone from the Bunun tribe.”

Like Savungaz, those who have reverted to their Indigenous names said their choices have more to do with embracing their personal identity than rejecting Chinese culture. But Taiwanese identity — and its links to mainland China — has become a politically divisive topic as relations between Beijing and Taipei further sour.

China considers Taiwan a part of its territory, and President Xi Jinping has stressed the importance of eventual unification, using increased military posturing as a cudgel. After Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen met with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) in Southern California recently, Beijing launched a three-day military drill to express its displeasure, practicing precision strikes and a blockade of the island.

Even though Taiwan’s Indigenous are a fraction of the population, many Han Chinese have also embraced Indigenous artists, music and traditions, in part to counter Beijing’s claim that the 1.4 billion people on the mainland and the 23 million people of Taiwan belong to one ethnic family. In last year’s annual identity survey by the National Chengchi University in Taiwan, a record low of 2.7% of respondents said they considered themselves to be Chinese. About 61% identified as solely Taiwanese, while 33% said they were both Chinese and Taiwanese.

Under Tsai, who is one quarter Paiwan, the government has promoted Indigenous culture and classified all languages used by local ethnic groups as national languages. A five-year plan to advance national languages starting last year includes standardizing writing systems for Indigenous languages and bolstering educational resources.

Kolas Yotaka, spokesperson for the Office of the President and a member of Taiwan’s Amis tribe, said her decision to use her Indigenous name is often the subject of political attacks, particularly from opponents of Taiwan’s ruling Democratic Progressive Party, which has a chillier relationship with Beijing.

A visit to California by the current president of Taiwan and a trip to China by her predecessor encapsulate the choices facing the self-ruled island.

After she became a DPP legislator in 2016, Kolas said the name on her Wikipedia page was constantly revised to her old Han name, Yeh Kuan-lin, even as her assistant monitored the computer, at war with anonymous editors. During that time, Kolas also proposed an amendment to allow ID names to be written with only Latin letters, which opponents criticized as an attack on Chinese identity and culture.

The 49-year-old former journalist started going by her Amis name in 2006. Kolas was her grandmother’s name, which means to separate the wheat from the chaff in her native language. Her Han name has little meaning to her, and was derived from the Japanese surname her Amis grandfather used under Japan’s occupation.

In her run for Hualien county governor last year, Kolas said, supporters worried that her Indigenous name might deter political donations, if Taiwanese people couldn’t read or write it. Some encouraged her, unsuccessfully, to use a Chinese name on campaign posters for broader recognition.

Despite such hurdles, Kolas believes younger generations have become more accepting of cultural differences. While she’s often maligned for using an Indigenous name, she said people have also reached out in texts or in Facebook messages to her to share small triumphs in going by their own native names.

“It’s become the mini-revolution of my life,” she said.

As for Giljegiljaw, a member of the Paiwan tribe, his teammates in Cleveland found his name difficult to pronounce and took to calling him “Gilly.” He didn’t mind.

COVID-19 cut short his major league aspirations with the Cleveland franchise, which has since undergone its own name change, from the Indians to the Guardians, to salve criticism that its logo could be viewed as racially offensive.

Giljegiljaw now plays in the Chinese Professional Baseball League for Chinese Taipei — the designation that Taiwan’s international sports teams and other organizations use since the island is not officially recognized as an independent state.

In March, he played in the World Baseball Classic tournament in his hometown of Taichung, Taiwan, wearing his Indigenous name on his jersey like he did in the U.S. However, most of the time his uniform still sports the Chinese transliteration, and Chinese-speaking broadcasters announce him using tonal Mandarin and soft Gs, rather than the hard Gs of the Indigenous tongue.

To his father, Kuljelju Kungkuan, it sounds like the name of a stranger. He’s reached out to a sports broadcaster and a local legislator to request that it be pronounced in his native language. If the player has to be referred to in Chinese, his father prefers the Han name, which he chose in honor of a Taichung general.

Kuljelju, who still legally uses his Han Chinese name Chu Hsin-de, said he was initially concerned about his son going through hardships from changing his name. Now Giljegiljaw’s family sends him messages of encouragement, calling him by his childhood nickname, Giyaw, and telling him to keep up the good work.

“If I can reach people through playing baseball, and let people know who we are, then maybe there will be more school kids who will think: I also want to use my Indigenous name,” Giljegiljaw said. “I think this would be a huge honor.”

Yang is a Times staff writer and Shen a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.