Column: Can an anti-immigrant bill turn Florida blue the way Prop. 187 did for California?

When I heard about Florida’s plan to crack down on immigrants who lack legal status, I immediately thought of California’s Proposition 187.

The Florida bill, SB 1718, is a grab bag of punitive proposals, requiring hospitals, law enforcement and others to report the immigrants and criminalizing anyone who helps them.

It would even repeal state laws allowing college students who grew up in Florida but aren’t U.S. citizens to pay in-state tuition and to practice law.

Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican eyeing a run for president, is publicly supporting the bill, arguing that “illegal aliens” are destroying the Sunshine State. It’s expected to easily pass the Florida Legislature and become law as early as this summer, if it doesn’t get tied up in the courts.

Sound familiar, Californians?

That’s because this bigoted brouhaha is the latest grandchild of Proposition 187.

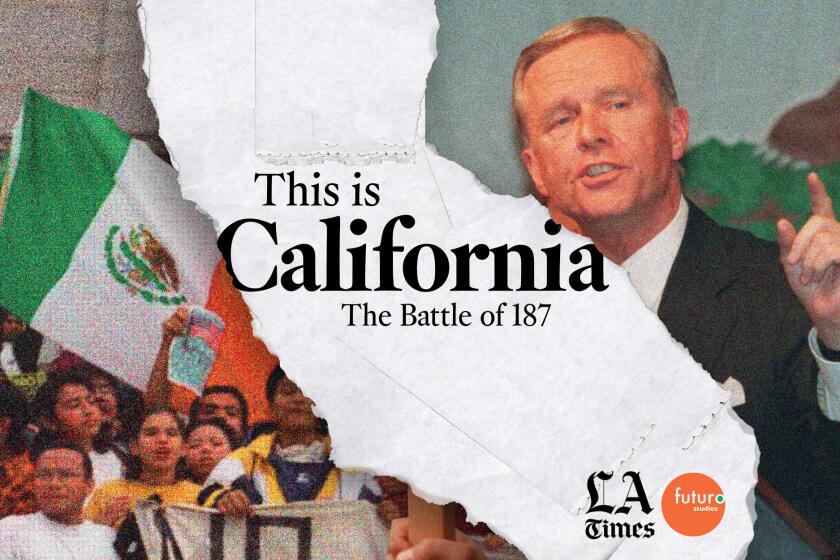

A podcast from the Los Angeles Times and Futuro Studios looks at how Prop. 187 helped turn California into the progressive beacon it is today.

The 1994 ballot initiative also sought to make life miserable for immigrants here illegally by denying them access to public education, social services and healthcare, and forcing government workers to turn them in.

Supporters said the move was necessary to save California; opponents called it racist. Voters approved the measure by a wide margin, but it never became law — a federal judge ruled it unconstitutional, and the state didn’t appeal.

The whole ordeal had a famously unintended result: It transformed California from a swing state into the deep-blue monolith it is today.

Young Latinos, many of whom staged school walkouts or joined boisterous rallies, registered to vote Democrat and fill elected offices from school boards to the state Legislature to the U.S. Senate — what’s up, Alex Padilla! The Republican Party, which enthusiastically backed Proposition 187, was cast into the political wilderness and is now as relevant in statewide elections as the Bull Moose Party.

Democrats across the U.S. have recited this history like an incantation every time GOP officials push xenophobic policies in states where Latinos are emerging as a political force.

They’ll point to 2006, when a congressional bill against illegal immigration sparked the largest protests since the Vietnam War and a record Latino turnout in the 2008 presidential election. Or 2010 in Arizona, where SB 1070 and the draconian policies of Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio spurred Latinos to support President Biden 10 years later, helping him win the state.

That’s why my knee-jerk reaction was that SB 1718 would be DeSantis’ downfall and a turning point for Florida politics. No way would Latinos in a state with a Spanish name that is home to refugees who came with next to nothing and found the American dream, and where Miami stands as a capital of Latin America, would allow the Republican-dominated Legislature to pass it.

But oh, wait. It’s Florida.

Progressive Latinos in California and beyond have long stereotyped Florida Latinos as crazy conservative cousins whose politics seem to get redder with each election cycle.

Cuban Americans remain a Republican bulwark. But newer immigrant groups — Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Colombians, Brazilians — have also drifted toward the GOP because of a general belief that Democrats are too soft on leftist leaders in their countries of birth.

Donald Trump tapped into their anti-communist fears and increased his share of the Florida Latino vote from 35% in 2016 to 46% in 2020, which made national headlines. DeSantis, meanwhile, won 58% of Florida’s Latino vote in his 2022 reelection, improving on the 44% in his 2018 victory.

Democrats? Their cries of racism and their disinformation campaigns went nowhere, and they offered Florida Latinos little else.

Stoking this rightward turn are Cuban American politicians, who have so embraced the GOP’s culture wars that Florida International University political science professor Eduardo Gamarra told me that they’ve become “the new Anita Bryants.” That’s the former citrus industry spokeswoman who made national headlines in 1978 for leading a repeal of a Miami-Dade County law prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation.

As the presidential election nears, Democrats and Republicans are targeting Florida’s other Latino voters, not just Cuban Americans and Puerto Ricans.

I called Gamarra, an expert on Latino politics in Florida, because I wanted to know if he thought the Proposition 187 effect might happen there.

“Could it be possible that in the next cycle ... that Latinos will turn out in reaction to the bills?” he said. “Maybe. But if they come out, how are they going to come out?”

Gamarra is working on a survey that asks Florida Latinos how they feel about illegal immigration, which has increased in the state in recent years.

Last year, DeSantis authorized over a million dollars in state funds to fly 48 Venezuelan migrants from San Antonio to Martha’s Vineyard in a move he freely admitted was a political stunt.

“I know just from interviews and conversations with people that there is this view that this is the new Mariel,” he said, referencing the 1980 boatlift of over 125,000 Cubans, who were dismissed as criminals by U.S. media and even Cuban Americans.

“The way in which [these new immigrants] are being portrayed,” Gamarra continued, “is that ‘They’re not like us, they’re coming illegally, they’re chusma [riffraff], they’re like the marielitos.’ They’re saying, ‘Yes, we need to have order.’”

Multiple surveys have shown that younger Latinos are more progressive than their parents, and the professor sees that with his students on issues like abortion and LGBTQ rights.

But in Florida, “when you go and do the polling and do the crosstabs by age, you see that when [it’s an election], they’re not voting, and when they do, they vote Republican.”

Gamarra does see the state as an “outlier” when it comes to Latino politics. But Geraldo Cadava, a Northwestern University history professor who studies the issue nationwide, told me that SB 1718 could very well serve as a warning — to Democrats.

“There is a truth to the idea that Latinos care about immigration,” he said. “But it’s not the issue it once was ... DeSantis knows that an immigration crackdown is politically popular within the [Republican] party right now, so he’s doing this in Florida to boost himself nationally.”

Cadava noted that Trump made gains among Latinos nationwide in 2020, despite campaigning on building a border wall, describing Mexican immigrants as “rapists” and “bringing drugs, and bringing crime” and calling El Salvador a “shithole country.”

He also pointed out that Democrats are reaping diminishing returns by trotting out the parable of Proposition 187 without delivering results, citing a 2021 Equis Research study that found 51% of Latinos who voted in the last presidential election supported Trump’s push to limit refugees from entering the U.S., and 49% liked his plan to reduce legal immigration.

“Part of the frustration with Democrats and Latinos is that Democrats keep making promises that they don’t follow through on immigration,” Cadava said. “Latinos have heard from Democrats on immigration so much, they’re like, ‘OK, we know how you feel about immigration so much, but what else do you have?’”

The Proposition 187 effect doesn’t transfer to other places as easily as Democrats and Latino activists may think, Cadava said.

“Part of what was going on in California” in 1994 “was that Mexican Americans were thinking about their relationship with Mexican immigrants,” he said. “In California, there’s a long history of transnationalism and solidarity with migration” that is lacking in states with recent increases in Latino population that are passing anti-immigrant statutes.

That’s what makes SB 1718 so dangerous. If it passes with little pushback, conservatives can point to it as proof that anti-immigrant politics play well among Latinos. The days where Democrats could dangle Proposition 187’s legacy over Republicans, like the sword of Damocles, would be done.

And then what, Dems?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.