Forced to live in horse stalls. How one of America’s worst injustices played out at Santa Anita

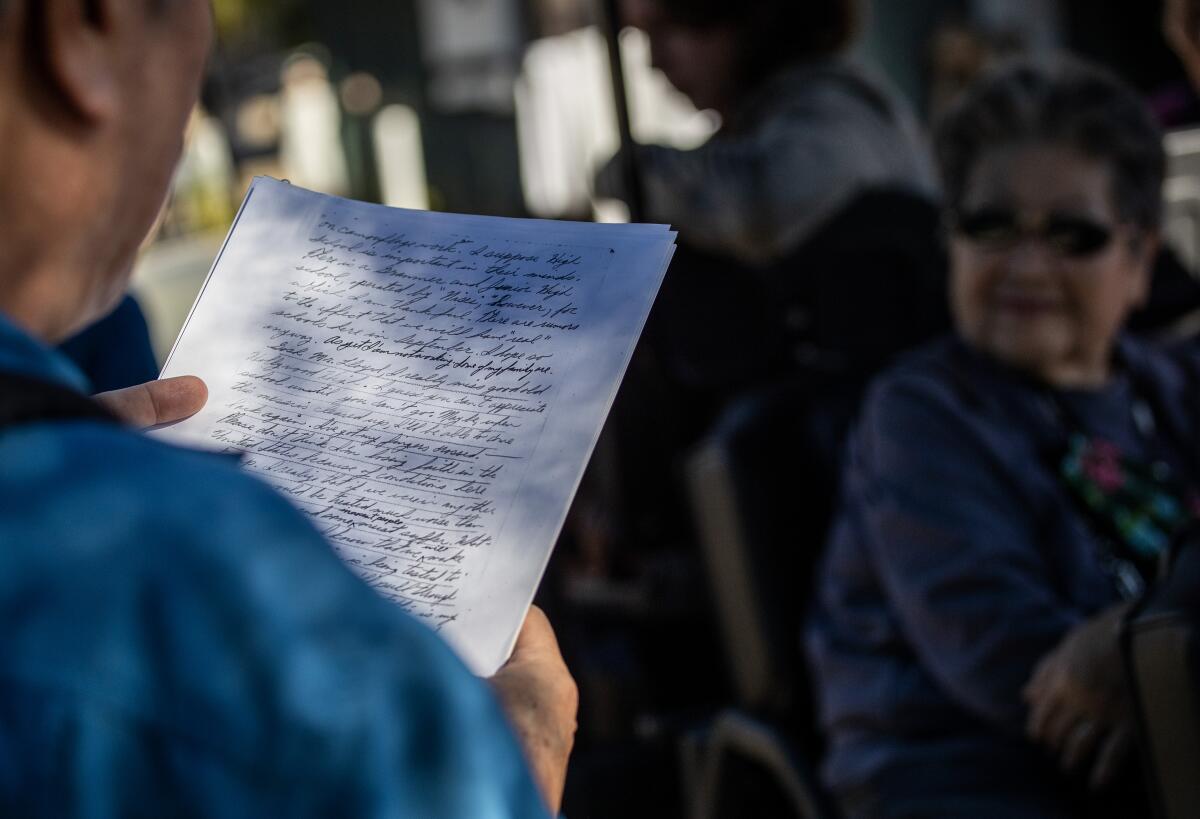

I wanted to make a bit of history real, so I brought along a wartime letter and planned to read it at the place where it all happened, at the horse stables of Santa Anita Park in Arcadia.

In the frenzied months following the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Empire — with horse racing suspended for the duration — a rushed wartime conversion transformed the racetrack into an “assembly center” to hold Japanese American people. My family was there, and they lived in the horse stalls.

On a softly sunny day in December, I joined a group of Japanese Americans on a tour of Santa Anita, where track officials described the living conditions at the camp.

Some of our party had been incarcerated here, including 90-year-old June Berk. She led us into Barn 52 as though she knew where she was going. The thoroughbreds emerged from every door, ears perked and puzzled by our appearance. Berk went directly to a stall.

“Well, here it is,” she said of her government accommodations in 1942.

I peered into Berk’s stall — old wood with faded white paint. The air smelled of hay, manure and urine. After we left the barn, I asked for five minutes to share something. The golf carts carrying the elders were brought up, and I read in the shade of a tree that was there when Berk was incarcerated at age 10.

It was a letter written by my Uncle Ted to James Lloyd, his history teacher at Hollywood High School:

June 5, 1942, Dear Mr. Lloyd,

Forgive me for not writing sooner. My only excuse is that I’ve been rather busy getting settled here at Santa Anita. On the morning of April 29, we (my family) got up at 4 a.m.... We went to the corner at Lexington and La Brea where we boarded buses.… After an uneventful trip of about 2 hours, we arrived here.

At the gates an armored car armed with about three machine guns greeted us. We were registered, given our mess-hall buttons, and were taken to our home — a horse stable! Since there are seven in our family at the present, we were given two stables. My mother and sister just sat down and cried.

It was the first of nine letters Uncle Ted, then 18, sent to Lloyd. Our party fell silent, and some track workers paused to listen as my uncle described the indignities of camp life:

The showers (200 for 18,000 people!) are about ½ mile away. By the time one gets back from taking a shower, he is ready for another one.… Dirty water flows from the wash and showers, flows right into a small stream that runs through the camp. It is left uncovered and therefore stinks to holy heaven.

Can you imagine, they ration toilet paper to us. One roll to 4 persons — for two weeks! Golly, I wonder what will happen if we all get diarrhea or something.

Our tour group included formerly incarcerated second-generation nisei who had lived the history: We had Min Tonai, 94 (then 13); Hal and Barbara Keimi, 91 (then 10) and 87 (then 6), respectively; and Bacon Sakatani, 93 (then 12). A quick word on the nisei: They are famous for nicknames some non-Japanese found easier to say and remember than their given names. The youngest was Sei Miyano, 83 (then 3).

They are our respected elders now. The last witnesses. But thanks to his letters, my Uncle Ted — Ted Fujioka — is a witness too, and how our family came into possession of those letters is a story in itself.

The assembly centers seem a minor note in the incarceration story that ran from 1942 to 1945. But they were the important first stop, the holding cell for thousands between a regular life of American freedom, to a long train ride to one of 10 permanent “relocation camps” far inland.

Santa Anita became the largest of the West Coast assembly centers, with 18,000 Japanese American souls imprisoned there. (A young George Takei lived at Santa Anita; oh, my.) All the camps, whether temporary like Santa Anita or permanent like Manzanar in the Owens Valley, were secured with searchlights, guard towers, barbed wire and armed guards.

Inside the wire there may have been flower arranging and sports, but these were still prisons. By war’s end seven men had been gunned down by Army guards.

Late last year, Santa Anita officials reached out to the Japanese American community to seek input because renovation plans will probably affect some of the historic 1930s horse stalls.

Our friendly and accommodating Santa Anita hosts, Nici Boon and Stephanie Kingsnorth, consultants, and Pete Siberell, director of special projects, gathered us at the grandstand for introductory remarks. They emphasized how they don’t have much history on the barn-barracks, making community input vital before moving ahead with the renovation.

I was a youngster in the tour, belonging to the sansei, or third generation, born mostly after the war. My older brother, Dale, was born in camp in 1943. My father was drafted out of camp into the Army.

Horses stared back at me as I looked up and down the barn’s corridor. I couldn’t hear anyone else as I took it in and thought of my family. Cheerful Uncle Dick probably began to tidy up. I know that beautiful Auntie A.Y. cried (her white teachers had trouble pronouncing “Ayako,” so another nisei nickname was born).

And poor Grandma Chiyo was unaccompanied. Her husband, Shiro Fujioka, was the Japanese editor of the bilingual newspaper Rafu Shimpo, and he had been taken away the day Pearl Harbor was attacked. Using a previously prepared list, two LAPD detectives barged into the family home on the afternoon of Dec. 7 and hustled grandfather away without his medications. He was held by the FBI on Terminal Island.

The FBI thought they had the right sort of man — a first-generation issei immigrant who was bilingual, could write in English and was held in high esteem in the community. But he was no spy or saboteur. He was a journalist who had covered the 1905 Portsmouth Conference in Maine that settled the Russo-Japanese war, adjudicated by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Shiro Fujioka had studied at Columbia University and apparently loved it. He believed in the promise of this country and established his family here. That promise was broken on Feb. 19, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, stripping away the constitutional rights of 120,000 people of Japanese descent and sending them to incarceration camps.

Farms, savings, businesses and homes were lost. Children had to say goodbye to pets. A man went mad and lay his neck on a train track to behead himself.

Men like my grandfather were held separately from their families in places like the Tuna Canyon Detention Station in the hills above Los Angeles. The leadership of our community disappeared, and their nisei children, like Uncle Ted, had to grow up and assume responsibility fast.

Two months into his time at Santa Anita, Uncle Ted wrote:

Dear Mr. Lloyd,

Thanks very much for your recent letter. As you did with my letter I took the liberty to show it to my brothers and sisters. It did so much to raise the morale of all of us … happy to know that there were still understanding, clear-thinking, fellow American citizens on the “outside.”

I am sure that we on the “inside” really have nothing to fear from rumors of our deportation, our loss of our right to vote, or even our outright loss of our American citizenship. As you know, there have been suggestions made by various people and organizations along these lines.

Though their country had turned its back on them, detainees at Santa Anita contributed to the war effort by weaving camouflage nets. Uncle Ted referred to them in this letter:

Conditions here seem to be getting better. That is, the food condition is much better. Maybe this change to the better is due to the administration on its own will, but I am inclined to think that it is due to the recent camouflage workers’ strike. You have probably read about it in the papers or over the air – “Japs go on strike at S.A. because of sour kraut and weiners, a typical German dish.”

The saga of the wartime incarceration of my loyal and patriotic Japanese American family is a part of who I am. My parents married because of the impending removal. My mom’s health may have been affected. Grandfather suffered and never worked after release. My activist Aunt Sue pushed for the establishment of the Manzanar National Historic Site.

It’s a family affair for us, and it’s heroic and sad and very American. I thought I knew the story well, how anti-Japanese hysteria swept up 12 people on my mother’s side and five on my dad’s. But about a decade ago came a revelation in the form of an email from Kathie Lloyd of San Jose. I was floored as I read it.

“You and I don’t know each other,” she wrote, “but we have a family connection through our relatives.… Recently I discovered that my father and your uncle kept a correspondence going during the time that Ted was interned first at Santa Anita Assembly Center.… My father never mentioned this to me and I only recently made this discovery while going through a box of things in my garage.”

I had done theater monologues using letters Ted had written to family members. Kathie found me in an internet search after discovering the nine letters among her late father’s effects.

“My dad’s notes indicate that keeping up his correspondence with Ted helped him (my dad) ‘channel his outrage’ at the time of the internment,” she wrote.

There are nine letters in all, from the Santa Anita stalls to when Ted volunteered for the Army after graduating from high school at the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming. Kathie mailed me photocopies and I began to hear the voice of an uncle I never met. Somehow, he was convinced that prejudice could be defeated:

Dear Mr. Lloyd,

… Perhaps I’ll never see the day when America will be truly democratic in the real sense of the word, but I’ll have helped towards that goal. I’ll have done my best. The people that I have met, men from every walk of life — the youngster of 18, married men with children, Caucasians, Negroes, Mexicans and Nisei — have taught me much about human natures, emotions, loves and dislikes.

One young, intelligent fellow about my age, a Negro, taught me the most. His thoughts, ideas, hopes and goals, why he volunteered, his thoughts on race prejudice, and inequality ran parallel to mine. We must work not only for ourselves, but for all other minorities as well, for if we don’t we can never hope to make this country the melting pot of the world.

My mother’s family, the Fujiokas, had lived in Hollywood on Gordon Street just south of Sunset Boulevard. A small Japanese American enclave took hold there in the early 1900s.

Before the war — the phrase every boomer heard growing up — my aunts and uncles attended Grant Elementary, Le Conte Junior High and Hollywood High. The second-youngest Fujioka son was Ted. He was something of a golden boy, good-natured, a natural born leader.

Uncle Ted served in the famed all-nisei unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, sometimes called the Purple Heart Battalion because of all the killed and wounded. Then 19, he had made it through the legendary “Rescue of the Lost Battalion,” where the nisei suffered huge losses breaking through German lines in France to rescue trapped American soldiers.

But a week later, as he carried wounded buddies, a German barrage zeroed in and a shell slammed into a tree. The “tree burst” sent shrapnel and splinters flying. He dove but was killed.

The telegram that began, “We regret to inform you …” was delivered behind the wire at Heart Mountain. In transit to Ted was a letter written by his father, Shiro. It was later returned unopened. His father had closed with, “Do your best duty as an American soldier.”

The resettlement after the war was rough on many. Uncle Sam gave you $25 and a train ticket home, if it was still there. Some lived in silence with buried trauma. Ted’s younger brother, my Uncle Babe, the athlete, could barely speak of his brother even years later.

A sansei buddy of mine once invited me over in the mid-1960s. His home was dark and quiet, the air stifling and reeking of mildew. His mom was there. She apparently never ventured out. Another nisei woman I heard about hoarded toilet paper, filling an entire closet. Just in case.

My mother couldn’t watch the final battle in the 1951 movie about the 442nd, “Go for Broke!” The GIs rise up and yell, “Go for broke!” — the unit’s motto. Some die, but they keep going, and I cheered like every Japanese American boomer boy because this movie was our story and we were the heroes this time.

But I saw how Mom went to the bedroom to cry alone for her baby brother. Years later, while she was in a waking coma, with eyes shut tight for weeks, she called out, “Teddy!”

What would Ted have become? Would he have gone to college on the GI Bill? Would he have taken to the road on a search for self as his buddy Albert Saijo did? Saijo wrote poetry and hung out with the Beats. He and Jack Kerouac drove to New York to meet with Allen Ginsberg.

Private First Class Ted Fujioka is buried at the Epinal American Cemetery and Memorial in France. It is very green and quiet there. He is surrounded by 5,000 fellow Yanks, and on Ted’s birthday — 19 forever — our French friends take flowers and send pictures of their visit. Merci to the 442.

The original letters he wrote to Lloyd are now part of a historical collection at Heart Mountain. His voice, and faith in a country that betrayed him and his family, is still heard:

Gosh Mr. Lloyd, I really miss good old Hollywood High.… Please don’t think I’m losing faith in the United States because of conditions here at camp.

I know that we will make the best of it. Our patriotism is being tested to the utmost, but I think we’ll pull through smiling.

———

Kunitomi is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.