‘What’s up! I can’t read.’ O.C. resident goes viral after schooling left him functionally illiterate

It was just after dawn, and TikTok’s unlikeliest literary hero was running late.

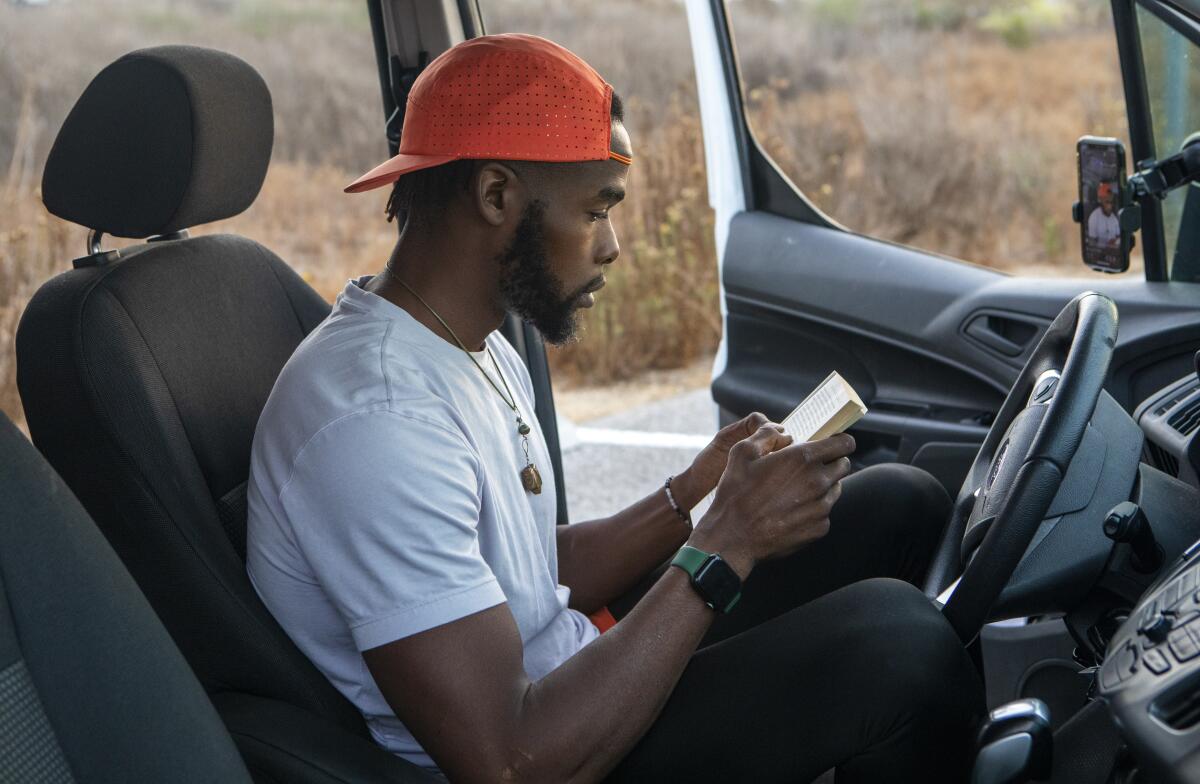

Oliver James, 34, backed his white Ford cargo van into his favorite spot at Upper Newport Bay Nature Reserve in Orange County, his face aglow in the autumn sunlight as he rushed to set up his first livestream of the day. He tugged a makeshift curtain behind the driver’s seat, snapped his cellphone into a mount by the side mirror, and pulled a gently loved paperback from his knapsack.

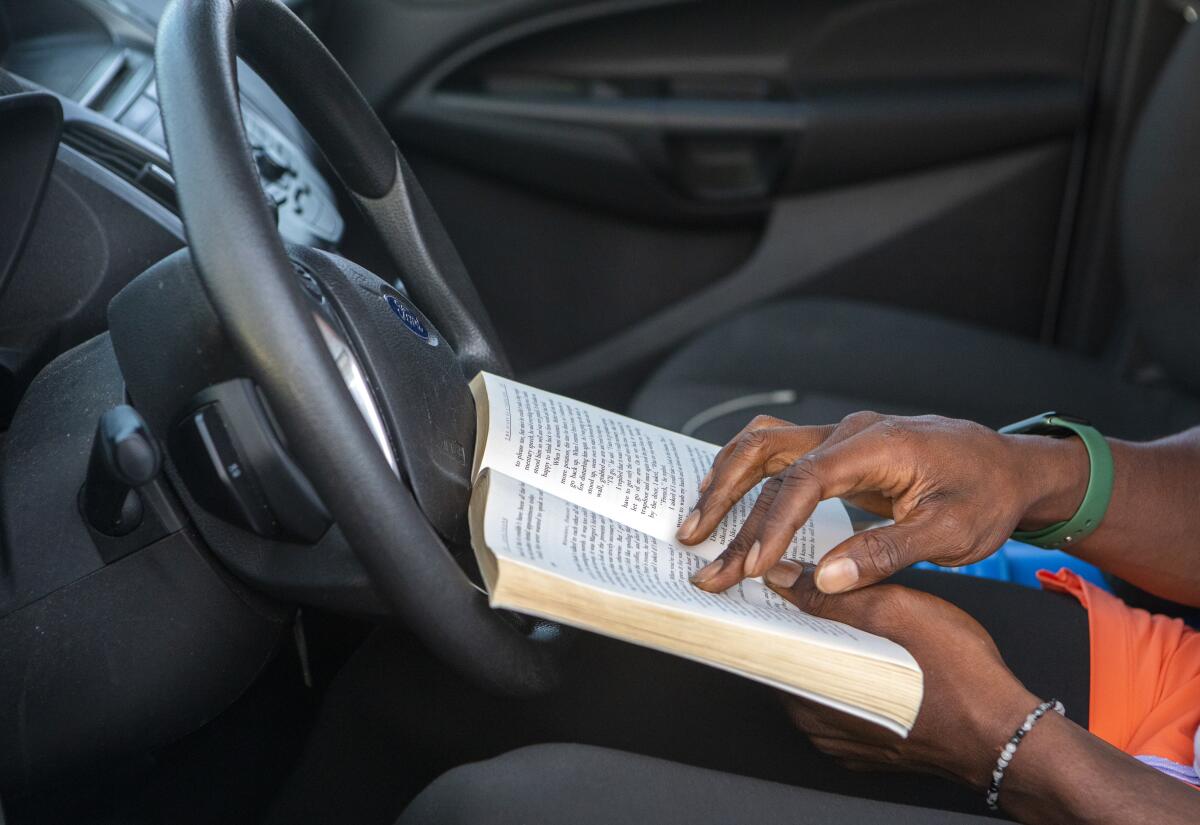

“It’s a new day, a new start,” James told the camera, flipping to page 190 in “Anne Frank: Diary of a Young Girl” as hundreds of strangers logged on. “We’re going right up to the top — can’t waste no time!”

With that, he began reading aloud from the 75-year-old memoir — a book that everyone in the audience had read.

James is not a mellifluous reader, though he shares the blinding smile and infectious energy of other viral creators on the popular video app. A personal trainer by trade, he has never penned a bestseller, taught English, studied library science or appraised a first edition.

Yet his six-figure following puts him in a rarefied tier of “BookTok” influencers, ahead of the New York Public Library, The Last Bookstore and all the “Big Five” publishers combined.

“I snuck in through the back door,” he said of his sudden success. “I snuck in from the back and have more followers than most #BookTok people.”

Indeed, his meteoric rise among the app’s literary luminaries has proved the year’s biggest plot twist.

It began with five words.

“What’s up! I can’t read.”

::

If you’ve made it this far, you likely have little memory of how you learned to read.

Partly, that’s a function of mechanics: Formal phonics instruction, which builds literacy from letters and sounds, is only newly in vogue among today’s grade-schoolers, after decades of disfavor in American education. In California, it was not taught at all from the Reagan era through the impeachment of President Clinton.

Yet even children who study this “science of reading” rarely recall the painstaking synthesis of sign and sound that first alchemized tree pulp and petroleum ink into Desmond Cole of “Ghost Patrol” and Matilda Wormwood, Roald Dahl’s 5-year-old protagonist from the book of the same name.

At some point, for most of us, it just happened.

“People really can’t imagine what it is to exist without being able to read,” said James’ partner, Anne Halkias, 38. “I don’t think people understand how much extra work you have to do.”

Because we can’t remember it, illiteracy can seem total, akin to the formless darkness many sighted people imagine blind people see.

But for adults like James, the reality is both brighter and blurrier than that.

“There was some foundational stuff there,” Halkias said. “He knew his alphabet. He knew certain words.”

But he lacked the skill to tap out a text message or untangle the instructions in a video game. He couldn’t parse a job application, browse a takeout menu, recognize a comma or pronounce a contraction if he saw it on a page or screen.

In terms of fluency and comprehension, James was years behind Halkias’ 10-year-old son.

“I remember them telling me [I] was at a first-grade reading level when I was in high school,” the TikTok star said.

Anyone who’s read with a first-grader will recognize the flat affect, halting pronunciation and bursts of fluid prose that characterize James’ live TikTok broadcasts, even after months of practice.

His dash-cam confessionals look nothing like the polished “shelfies” and breathless reviews that first surfaced #BookTok from the app’s vast warren of subcultures, transforming its bespectacled

influencers into kingmakers of the publishing world.

The typical viral BookToker is a white woman with statement glasses, annotations on brightly colored page markers and stacks of immaculate hardcovers in her to-be-read pile.

James, by contrast, is a dark-skinned Black man with a trim beard and clipped salt-and-pepper locs who mostly films from his van. In October, close to a million people watched him check out his first library book. In November, tens of thousands saw him build his first bookcase.

For the weeks he was reading “Anne Frank” this fall, close to 100,000 TikTokers tuned in every night to watch.

“I didn’t do a Live [one night], and they’re messaging me in the middle of the night,” James said, bemused. “Like, ‘Are you OK? Why aren’t you live?’”

To the denizens of BookTok, James’ inability to decipher the symbols that give meaning to the world seems like a witch’s fairy tale curse.

But experts say it’s all too real.

“This isn’t a rare story,” said professor Subini Annamma of the Stanford Graduate School of Education. “His story is a story of how the education system fails Black disabled kids.”

::

Before he went viral, James rarely spoke about his disability, or the schooling that left him functionally illiterate.

In fact, he’d tried for decades to forget the segregated classroom in Bethlehem, Penn., where he languished from second through fifth grades.

But the flood of attention since his TikTok debut washed up memories he’d buried back home in the former steel town.

“When I was in elementary school, I was in special education,” James explained in an early viral clip. “They used to be able to put their hands on us.”

In his telling, violence was the norm in the class where he landed after being diagnosed with ADHD and other learning disabilities. (He also has obsessive compulsive disorder, though he says he was not diagnosed as a child.)

While his peers progressed from Shel Silverstein (“The Giving Tree”) to Roald Dahl (“James and the Giant Peach”) to J.K. Rowling (“Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone”), James “just sat there” filling in worksheets, he said. Defiance was met with armlocks, chokeholds and body slams.

School is supposed to be a safe space, his new fans responded. Several asked if his former teacher was in jail.

But Annamma and other experts said what happened to James is not only legal, but textbook.

“He talks about being held with his arms across his chest — that’s restraint and seclusion,” a controversial practice that is disproportionately used on Black kids with disabilities, Annamma said. “That’s about compliance. It’s not about learning.”

Black students such as James are far more likely to learn in segregated special ed classrooms, where such physical discipline is the rule, federal civil rights data show.

“I ended up getting restrained two, three, four, five times a day,” he said. “It was torture.”

The memories bubble up from his body as he talks during an interview. He becomes his classmates, neck craned and eyes bulging in terror. His teacher, racing toward him in a lather. His muscular arms encircle his chest, hauling him up on his tiptoes. Then boom — 9-year-old Oliver hits the wall.

“I was just crying and crying and crying and crying,” he recalled recently, his shoulders slumped as he replayed the moment in the small Costa Mesa apartment he shares with Halkias and her son. “But I also remember that feeling of, like, [the teacher] won.”

The feeling haunted him through his teens, playing running back for a high school he never attended. He told his teammates he was enrolled at the vocational school down the block. In reality, he took the short bus from a segregated special ed program 20 minutes away.

It stalked him on the streets, where he briefly trafficked guns to help support his mother, court records show. It followed him to federal prison, where he spent his early 20s.

Rather than insulate him from mistreatment, as it often does for white children, a disability diagnosis pushed James to the margins, as it does for many students of color, said professor Jyoti Nanda of Golden Gate University.

According to the Department of Justice, at least a quarter of incarcerated adults spent their school years in special education.

After prison, James fell into fitness, first in Bethlehem and then in Orange County, where he woos wealthy clients with roadside acrobatics and breezy fits of strength. He dreams of becoming a motivational speaker, but makes his living as a personal trainer, advertising his business doing chin-ups on street lights, push-ups on sidewalks, one-armed handstands in the median.

“If you knew how to read, you probably wouldn’t have to do this,” he remembers telling himself.

But every time he tried, the feeling overwhelmed him.

“It’s like someone’s holding you upside down, and your blood’s rushing to your head — you know that feeling?” James explained as he and Halkias sorted the new books fans had sent him. “And then at the exact same time there’s also water dripping down your face, and [it’s] like someone’s holding your arms from wiping the water off?

“That’s how it feels every single time I read a word. I feel that feeling the whole page.”

According to BookTok, that sentence should be in past tense.

James is a reader now, his fans insist. Finishing “Anne Frank” and “The Outsiders” by S.E. Hinton proves he’s overcome the poverty he grew up with and the racialized trauma he suffered in special ed.

Not everyone is thrilled with the reaction.

“There’s a lot of ‘I’m the nice savior white lady who can help you with this,’” said Annamma, the Stanford professor.

Her observation echoed broader criticism of BookTok, which has overwhelmingly elevated white authors and influencers above writers and readers of color.

“I really hope [James] gets connected with the Black disabled community,” the scholar said. “He doesn’t have to be someone’s pet project.”

In the viral version of James’ story, he whispered the five magic words to the algorithm — “What’s up! I can’t read” — and BookTok appeared to grant him his wish. Literacy. And an audience of thousands to cheer him along.

In reality, BookTok discovered him in medias res — in the middle of his journey.

“I did it for a whole year with no one on there — I just talked to the camera,” James said. “I used to be on there for two hours with zero people.”

Then one day while he was sitting in his van, the magic words just came out.

Ten minutes later, he was internet famous.

::

There’s nothing mysterious about James’ inability to read. The real question is why he decided, at age 33, to learn. Or at least to try.

The reason? Last December, he found out he was going to be a father.

“That was a big surprise,” James said. “A very, very, very, very, very big surprise.”

In Halkias’ telling, James’ first response was panic. Then she suffered a miscarriage. When they decided to try to have a child, James committed himself to reading every day. He did it live on TikTok to keep himself accountable.

“I just wanted to read for a little bit, maybe a couple of people like it, and just go from there,” he said. “I just wanted to get these things off my chest.”

He read doing push-ups, practicing handstands and skating at the beach. He confessed his secret at least half a dozen times before it landed him on anyone’s “For You” page.

To be sure, landing on BookTok helped. Librarians showered his efforts with praise. Teachers noticed when he improved. Fellow readers sent stacks of their favorite books to his door: “Black Buck” and “Watchmen” and the Percy Jackson series, compliments of complete strangers.

For a time, at least, the community embraced him.

But it didn’t teach him to read.

He did that himself, a word at a time.

One day, he hopes, he’ll teach his son.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.