How a twice-convicted con artist went from scamming Manhattan elites to L.A. dive bars

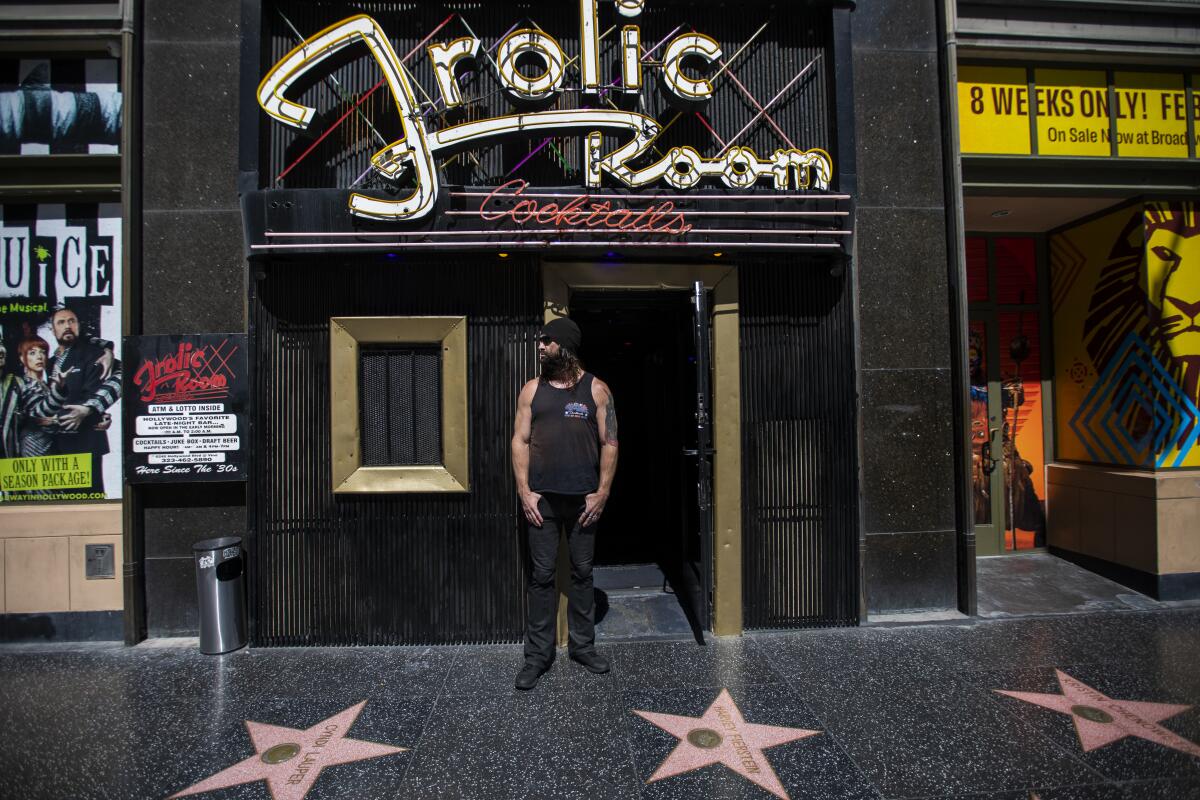

David Bloom swore he knew Netflix co-Chief Executive Ted Sarandos. He flashed email exchanges with Rams executives and promised Super Bowl tickets to fellow dive bar denizens in the dark confines of the Frolic Room.

Regulars say he favored vodka sodas at 11:30 a.m. at the Walk of Fame watering hole. He told one patron his net worth was $75 million. A bartender said Bloom routinely made overtures to buy the near century-old establishment, once a favored haunt of writer Charles Bukowski.

Bloom’s boasts were the fact-lite braggadocio of a dive bar day drinker. But some were taken in by the 58-year-old New Yorker.

James Duffy said he raced to finish a draft of a screenplay that Bloom promised to show Sarandos. Hours before Super Bowl LVI kicked off at SoFi Stadium, 15 people showed up at Frolic Room to claim Bloom’s promised tickets. Their purported benefactor was nowhere to be found.

The mere mention of Bloom’s name at Frolic Room now elicits groans and four-letter words. But the lies he told there were largely harmless. In other parts of Hollywood, however, Bloom allegedly sold fictions with serious consequences.

According to police and several of his alleged victims, Bloom spent most of 2021 telling neighbors and people he met in bars he could sell them shares of Instacart, Coinbase and Soho House before the companies went public. In some cases, he promised people they would reap more than 10 times what they invested.

Twelve of them handed Bloom more than $190,000 combined, according to Capt. Al Lopez of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Commercial Crimes Division. But the only person who profited was Bloom, who didn’t own any of the stocks he was selling, Lopez said.

Bloom’s victims — many of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of impacts on their professional lives — said they were seduced by his confidence, projections of wealth and near encyclopedic knowledge of financial power players.

“He would name-drop so many people ... he approached me with it and talked it through and even though I didn’t fully comprehend it, it seemed like a good investment opportunity,” said one person who gave Bloom at least $10,000. “I sound like an idiot now.”

Unbeknownst to those who had brushes with Bloom in recent years, the man making promises he couldn’t keep across Hollywood had sung this song before.

In the late 1980s, he earned the nickname “Wall Street Whiz Kid” after bilking more than 100 people — including his grandmother — out of a combined $15 million in an investment plot that drew the attention of the federal government.

According to court records, police and interviews with his associates and alleged victims, Bloom has spent the last three decades scamming his way from high-society Manhattan to L.A. dive bars, leaving people in ruin along the way.

Bloom did not respond to requests for comment. It was unclear if he has retained an attorney.

::

When David Bloom launched the Greater Sutton Investors Group in the 1980s, he was not a registered financial advisor. His only background in finance stemmed from the fact that he’d grown up rich.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Born on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Bloom vacationed in the Hamptons and attended an exclusive prep school before studying art history at Duke University, according to a New York Times article. While at Duke, he launched an investment group that allegedly paid off small profits.

Bloom set his sights higher when he returned to New York. He mostly targeted marks in their 50s and 60s — including his parents’ wealthy associates — claiming his investment clientele included Bill Cosby and members of the Rockefeller family, according to published reports.

None of it was true. But he still pulled in more than $15 million from roughly 140 clients.

Bloom only invested in himself, using his clients’ funds to bankroll a lavish lifestyle. He bought million-dollar paintings, a Manhattan condo, a Long Island beach house and an Aston Martin. The swindle landed Bloom in newspaper headlines — where he earned the Whiz Kid moniker — and inside a federal courthouse.

Bloom pleaded guilty to mail and securities fraud in 1987. He was sentenced to eight years in federal prison and barred from taking part in the securities industry for life.

Records show he was released from prison in 1994. But the Whiz Kid was back in action by 1999.

Bloom was a midday regular at Houston’s, a high-priced hamburger bar in Midtown Manhattan, according to a report in the New York Observer. This time he introduced himself as David Daly, claimed he drove a Bentley and reeled in a few bar regulars with sound investment advice.

He told them he had access to what he called “gift I.P.O.’s,” according to the Observer. If they invested with Bloom before the companies went public, they would make a fortune, he said.

As a dozen people in Los Angeles would learn 20 years later, Bloom had a habit of selling things he didn’t own.

In 2000, he pleaded guilty to grand larceny and violations of business law, according to the Manhattan district attorney’s office. Bloom stole “in excess of $50,000” and schemed to defraud at least 10 people, court records show.

After a little less than five years in prison, Bloom was paroled in 2006. A few years later, he met the mark who would lead him to California.

::

Ask Nancy Ozeas about Bloom now, and the Santa Monica resident describes him as a “certified, verified sociopath.” In 2009, she called him her husband.

Ozeas said Bloom approached her the same way he approached targets from Manhattan to Hollywood — he sat down with a drink in hand and started talking. Ozeas doesn’t remember what they spoke about that night in a Manhattan bar, but she knows it didn’t feel like a first date conversation.

“He’s literally able to sit down and kind of very quickly figure out what to say to make himself indispensable in your life,” she said. “To be that person that understands you better than anybody else ever has. That was his charm.”

Initially, Bloom told Ozeas he was an investor but offered few specifics. Unlike many of Bloom’s victims, Ozeas looked into her suitor’s background and came across news reports about his criminal history.

“He apologized profusely. He said he loved me and he was going to change,” Ozeas said.

Despite strenuous objections from her friends and family, Ozeas married Bloom in 2009 and they moved to L.A. in 2011. She remembers Bloom struggling to find work, and doesn’t believe he was running any scams at the time, though she offers a caveat for nearly anything she says about her ex-husband.

“In retrospect, I have absolutely no idea if anything [he] ever told me was true,” she said.

Ozeas said Bloom found work for several years with a company that put advertisements on bus benches. When he lost that job, Ozeas said, he “started spiraling.”

Money kept coming in, but she never knew from where. Her husband talked about clients and went on business trips but offered few specifics. The couple were living in a sprawling art loft in Venice at the time, a property valued at $1.6 million last month, according to Zillow.

Ozeas remembers growing frustrated with her ex-husband. But after marrying a man her family couldn’t stand and moving across the country, she felt isolated, stuck in a world framed by whatever story Bloom was spinning at the moment.

Then one day in either late 2016 or early 2017, Ozeas came home to find collection notices for credit cards that had been opened in her name. When she confronted Bloom, it quickly became clear how he had been financing his business trips.

“We had gone on a trip to Italy, supposedly so he could meet with a client. We’d gone to London. Guess what?” she said. “I paid for it.”

As Bloom’s marriage was falling apart, another six-figure swindle was coming together.

Joshua Montoya, the 32-year-old owner of a Venice wine store, said he first met Bloom and Ozeas at a Lincoln Boulevard market where he worked in 2014. The couple always complimented the shop’s wine selection and “never, ever, mentioned money, business or finances,” he said.

As Ozeas and Bloom’s marriage was crumbling due to the credit card fiasco, Montoya said he and his business partner, Simon Mellor, opened a new store in Venice. While remodeling the new property, Montoya said they stashed $70,000 of inventory in a U-Haul.

The truck was stolen. Bloom found out. Montoya’s phone rang the next day.

“I have an opportunity that might help you out of this predicament,” Bloom said, according to Montoya.

Once again, Bloom claimed to have early access to a stock primed to explode. This time it was the social media platform Snapchat. At a time when the company was trying to turn Venice into a tech haven, Montoya said it was the perfect bait.

“There’s spray-painted Snapchat ghosts on the streets we were walking down. They’re throwing Snapchat parties. My friend works there,” Montoya said.

Bloom had told them he was an advertising man who sold billboards at properties such as the Westfield mall, and displayed drawings of future projects to back up his story. He also seemed as though he didn’t care if they invested or not, according to Montoya, who said that laissez-faire attitude only set the hook deeper.

“He never asked for a lot of money ... there wasn’t a red flag,” Montoya said. “He wasn’t like you should give me $25,000. He says if you want to invest $100, if you want to invest $1,000, whatever amount you want.”

Over the course of a month, Montoya and Mellor gave Bloom $101,000. Bloom took the men to meet with an accountant to discuss the tax implications of their pending windfall, they said. Months went by. The men said they asked for statements and quizzed Bloom on when they might start seeing a return on investment. Nothing came.

Eventually, Bloom became scarce around Venice, they said. Mellor started distributing fliers to other business owners in the area, warning that Bloom was a grifter. Even now, Mellor bristles at the mention of Bloom’s name and says he would have punched the Whiz Kid if he found him back then.

Meanwhile, Montoya was desperate. He’d borrowed the money for the Snapchat investment from friends and had planned to pay them back with the profits. Half-hysterical, he reached out to Ozeas.

“Josh, please tell me you didn’t give David any money,” Ozeas said, according to Montoya.

“That’s when my heart exploded,” Montoya said.

“I can definitively say he was the most destructive person I’ve ever met. I wish I never married him.”

— Nancy Ozeas

Ozeas filed for divorce in June 2017. Montoya and Mellor sued Bloom and Ozeas for fraud two months later. Both men insist she was in on the scam, and they allege she handled Bloom’s money, according to the suit.

The case settled in 2019, though the terms are not public. Bloom confessed to the fraud, according to a document filed by the plaintiffs’ attorney. Ozeas said she was barred from discussing the settlement, denied all wrongdoing and said she was just as much a victim as anyone else.

“I can definitively say he was the most destructive person I’ve ever met,” she said. “I wish I never married him.”

Montoya, Mellor and Ozeas all said they reported Bloom’s alleged actions to the LAPD’s Pacific Division. The men said they were shooed away by a desk officer. Ozeas said she was never contacted by a detective after her initial report.

Lopez, the LAPD captain, said there was no evidence any of them contacted police but also acknowledged he wasn’t working in Pacific Division at that time. He encouraged all three to come forward and cooperate with the current investigation.

From February to August 2021, Bloom resurfaced in Hollywood, once again promising windfalls to anyone willing to buy stocks he obtained before they went public, according to Lopez and several victims.

The victims requested anonymity but provided documentation that they had been in touch with police about Bloom in the last year.

From what the victims described, Bloom was repeating all his old dance moves. The owner of a West Hollywood restaurant said Bloom cozied up to him over wine and talk of film. Bloom positioned himself as a wealthy advertising salesman again, this time wanting to hire the restaurateur to open a second eatery in a building Bloom owned in the Arts District.

No such property existed, but when the victim’s restaurant went out of business during the COVID-19 pandemic, Bloom appeared with a financial opportunity. The restaurant owner said they gave Bloom $30,000 to get early access to Soho House shares last August.

At the time, Bloom was living at the luxury Villa Carlotta apartments in Franklin Village, according to several of his victims. The landmark building with Old Hollywood affectations was once home to actress Marion Davies and sits just across from the Church of Scientology’s Celebrity Center.

One Villa Carlotta resident who described himself as an amateur painter said Bloom was quick to compliment his canvases. Bloom was a chameleon, shaping his personality around his target’s interests, the Villa Carlotta resident said.

Marie Springer, an economics professor and author of “The Politics of Ponzi Schemes,” said scammers try to mirror their marks because people generally won’t believe a like-minded person is lying to them. She called it “just like me syndrome.”

“Their entire goal is to get people to trust them,” she said of con men like Bloom. “They are truly experts in listening for people’s vulnerabilities. They’re going to come across as the nicest guy or the kindest woman you’ve ever met.”

Springer warned that people should always check the Securities and Exchange Commission website before dealing with any broker. But she also said it’s common for people to fall for scams like the one Bloom is accused of running.

“People want to get in on the newest gadget, the newest gizmo ... we all really feel like we’re going to make it big,” she said.

Everything fell apart last September, according to several of the victims. Bloom allegedly spaced out his requests for money over the span of six months, but eventually the Villa Carlotta residents who hadn’t seen returns on their investments started talking. A few found the articles that had christened Bloom the Wall Street Whiz Kid.

A group of Villa Carlotta residents and other victims of Bloom’s most recent alleged scam confronted him at his apartment last September.

“At first he denied everything. He denied that he scammed us. He said, ‘I will pay you all back in the morning,’” said one victim. “But everything that comes out of his mouth is a lie.”

Bloom moved out of the building one month later, the victims said. Lopez said none of them have received restitution, and the LAPD investigation revealed Bloom had “very little money in his personal accounts.” Some victims said they received partial refunds from Bloom, but they suspect he simply paid them off with investments from other victims.

None of the victims or Frolic Room regulars who spoke to The Times have seen Bloom since February. A Frolic Room bartender said it’s not uncommon for people to come in looking for Bloom demanding payback. Most aren’t talking about money.

Bloom’s legal fate remains up in the air. He was arrested on suspicion of 12 counts of grand theft on Aug. 9 and released after posting $45,000 bail, according to Lopez, who says his detectives electronically submitted a case to prosecutors in August. A spokesman for the district attorney’s office said the case was not received by prosecutors until Sept. 13, but it is now being reviewed for charging.

Some of Bloom’s victims are more concerned with getting the word out about the Wall Street Whiz Kid than they are seeing him land in a courtroom. After three decades of swindles on two coasts, they said he’s probably only one dive bar chat away from finding his next mark.

“He already went to prison. It’s not going to change anything,” one victim said. “He doesn’t know how to work differently.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.