GREENVILLE, Calif. — Most days, Ken Donnell steals a moment to gaze at the forested valley that surrounds this remote grid of streets in the mountains.

Before the Dixie fire came barreling through the Sierra Nevada last year, leveling everything here but a few houses, businesses and a school, this was a charming — if dying — Gold Rush-era town that about 800 people called home. Now, much of the charm is gone along with most of the residents, replaced by the skeletal remains of conifer trees and the deathly silence of block after empty block.

But even as Donnell has mourned, his mop of gray hair a fixture at community meetings on how to bring the town and the surrounding Plumas County valley back to life, he has become grateful.

It’s good that Greenville burned down when it did, he believes. Sooner rather than later. Because one day, in a not-so-distant future ravaged by climate change, many of Northern California’s far-flung rural towns — founded in another time and for another economy — might not get rebuilt at all.

Gone could be the political and public will to spend hundreds of millions of dollars — with Southern California taxpayers footing a big chunk of the bill — to replace homes and businesses for a small number of people, knowing that it’s all likely to burn down again as extreme heat and drought keep decimating unmanaged forests.

“Resources are going to be drained,” Donnell predicted. “It’s just the reality.”

By our back-of-the-napkin math — which we calculated because no one in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration could provide an official tally — it will take about $1 billion just to rebuild Greenville. Only about 300 people plan to return, and climate scientists say the town could catch fire again in as little as 10 years.

“These disasters are going to occur more and more frequently,” Donnell acknowledged, “and in more and more places.”

We know it might sound far-fetched that a changing climate could one day force California to abandon entire towns in high-risk fire zones in the mountains, the way a handful of coastal communities have reluctantly embraced a “managed retreat” from rising sea levels.

But it’s really not. Not when most of both rural Lake and Butte counties have gone up in flames multiple times in the last few years, often displacing and sometimes killing residents. Not when eight of the 10 largest wildfires in the state’s history have occurred in the last five years, with the top three in Northern California.

“Whatever risk tolerances that we collectively decided were acceptable, for whatever reason, in whatever context, are no longer valid,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA. That’s because Californians built communities and infrastructure “in a particular historical context that no longer exists.”

As journalists, we’ve covered many of the wildfires that have laid waste to Northern California. The two of us have seen the flames up close and spoken to people as they’ve returned to their homes and ranches to find little more than rubble. Or, even worse, the remains of a loved one.

In a not-so-distant future ravaged by climate change, many of Northern California’s rural towns wiped out by wildfires might not get rebuilt at all.

We’ve seen the hope in people’s eyes when they talk about rebuilding, and seen the disappointment on their faces when nothing has changed years later. We’ve also heard the panic in their voices when smoke from a wildfire rolls toward a neighborhood recently rebuilt from the ashes of a previous fire.

We’re not climate scientists, disaster relief workers, bureaucrats or firefighters. But we’ve interviewed them all, and we’re merely saying out loud what many say quietly: Something must change.

What California is doing is dangerous and unsustainable, yet it continues down a well-trodden path, never hesitating to rally around people who have lost their livelihoods to a disaster, whether it be a mudslide or an earthquake — but especially a wildfire.

We are #ParadiseStrong, #SantaRosaStrong, #GrizzlyFlatsStrong and now #GreenvilleStrong. And we’ve spent billions in taxpayer dollars to prove it, along with ensuring that Pacific Gas & Electric, responsible for sparking far too many of these destructive conflagrations, is on the hook to pay billions more and to help rebuild.

We do this because it’s the morally right thing to do for our fellow Californians, many of whom are elderly and poor and don’t deserve the misery and uncertainty of losing everything but the clothes on their backs.

People like Donnell, whose home and business were wiped out by the Dixie fire — to date, the second-largest in California’s history.

But the cold, hard logic of science has a way of poking holes in emotionally driven policies and moral certainties. This is especially true when it comes to the profound environmental changes underway because of human-exacerbated aridification.

The same unprecedented drying of California’s climate that has pushed the Colorado River and Lake Mead to the brink of depletion, forcing Angelenos to conserve water in a bid to stave off further disaster, has helped create the perfect conditions for massive wildfires in our forests.

“The problem is, these are places that were already high-risk, but the risks have dramatically escalated from high to extreme,” UCLA’s Swain said. “It’s getting increasingly likely that we see these small towns in high-risk zones wiped off the map every passing year.”

California needs a plan for how and where we will live in the future.

It’s a pattern that raises uncomfortable questions about how Californians must adapt to live more sustainably in the future. Questions that many in government would probably prefer not to answer.

For instance, should we really be rebuilding every single town that is scorched by a wildfire, particularly if it means we’ll be putting people in mortal danger again?

Or would that money be better spent fortifying a larger, more urban community outside of a high-risk fire zone or restoring forests and watersheds damaged by wildfire, rather than, say, paying for new underground power lines and broadband internet service in the mountains of Greenville?

And if we don’t rebuild every town, which ones should make the cut? And why?

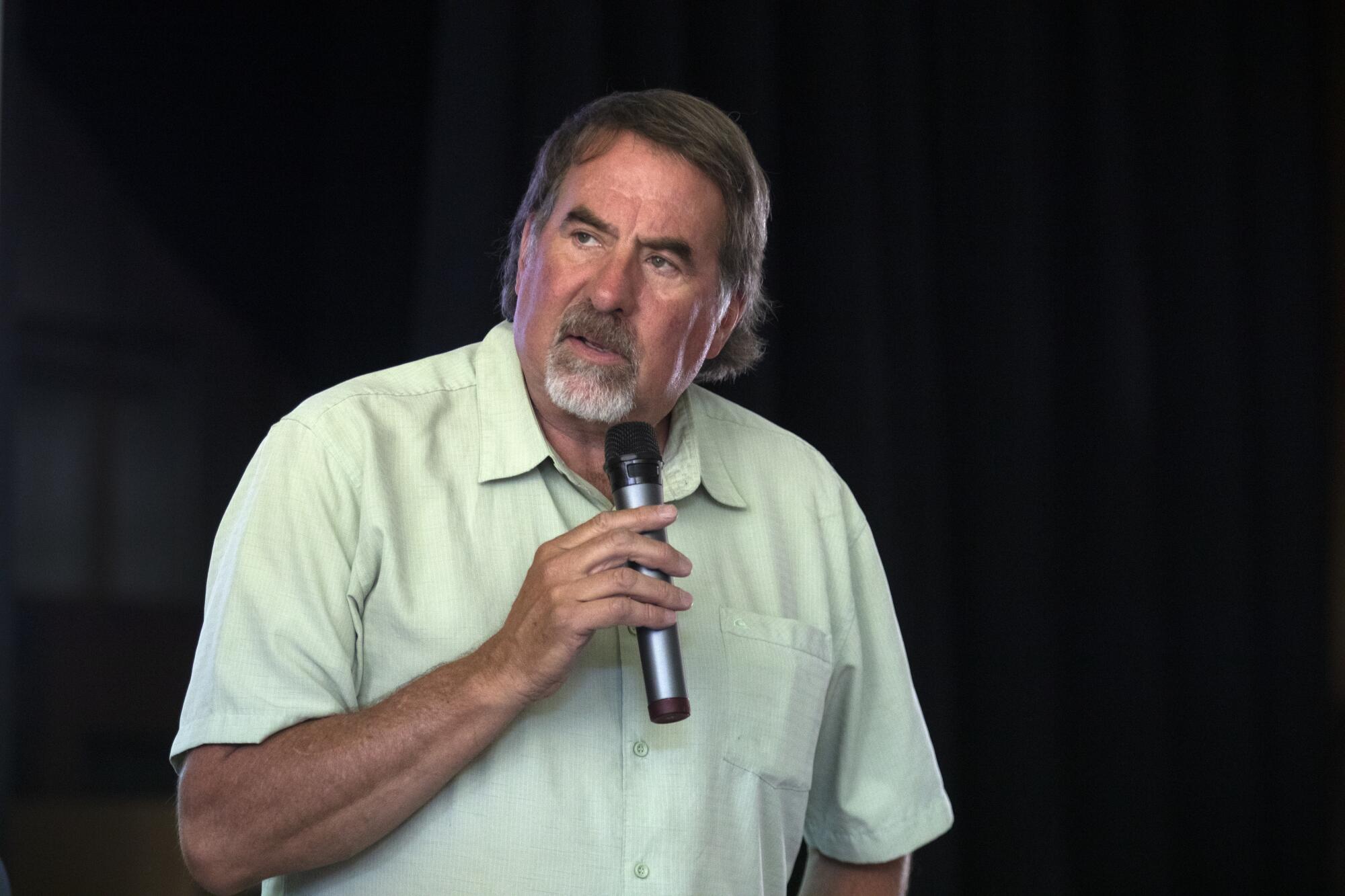

Even longtime Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-Richvale), whose district includes parts of Plumas and Butte counties, has questions.

“Honestly, how many billions can I keep going back to D.C. — to the well — asking for Paradise, Magalia and Greenville, and maybe a little bit for Doyle or whatever the next town is going to be?” he mused one morning in July. “I mean, that’s my job to keep asking. But it’s, you know, ‘Oh, you again? Another fire?’ I’ll ask every time, but how long will they keep listening?”

Like many people with ties to rural Northern California, Sue Weber scoffs at the suggestion that towns that burn down shouldn’t be rebuilt simply because of the ever-growing risk of catastrophic wildfire.

Weber is co-chair of the Dixie Fire Collaborative, the nonprofit coordinating the recovery of Greenville and neighboring Indian Falls and Canyondam, and “managed retreat” isn’t in her vocabulary. That would be akin to giving up on people — blasphemy for a woman who spent years as a nun, both as an assistant to Mother Teresa and leading an HIV/AIDS hospice in San Francisco.

Residents of rural communities are “pissed off,” Weber said with her characteristic, sometimes foul-mouthed frankness. “They feel the pain that they no longer can live the life they wanted to live.”

They didn’t keep up as California changed, she explained. First, as environmentalists championed a shift away from harmful but profitable mining and logging operations, and now as California moves to close prisons as Democrats wisely rethink a criminal justice system that has allowed mostly white, rural towns to treat Black and Latino prisoners as a source of revenue.

And in an era of Trumpism and political brinkmanship, the threat of climate change coupled with the lack of urgency around forest-thinning projects and prescribed burns that can greatly reduce wildfire risk has only fueled new conspiracy theories and further inflamed right-wing extremism.

“There’s a lot of folks who are trying to push people out of rural areas or rural communities, and they’re saying they shouldn’t be there,” said Jonathan Kusel, founder and executive director of the Sierra Institute for Community and Environment, repeating a popular refrain among residents of Northern California.

Most members of the Dixie Fire Collaborative choose to see wildfire as just another acceptable risk to be managed. Just like rising sea levels in San Francisco, flooding in Sacramento and drought in Los Angeles. The threat of climate change is everywhere, they point out.

“We all kind of pick our poison, don’t we?” Kusel added.

The real problem, many here argue, is that Greenville isn’t seen as an equal to San Francisco or Sacramento or Los Angeles. Indeed, it’s a town that most Californians didn’t even know existed before the Dixie fire wiped it off the map and one that most wouldn’t miss if it never returned from the ashes.

“This was not a thriving community, it was a dying community,” Weber said.

It’s hard to justify rebuilding a town that had a shrinking population long before a wildfire evicted everyone else. So, more than anything, she has set out to create a reason for Greenville to exist.

“As hard as it is and as hard as it’s going to continue to be, we have this opportunity to build it back and thrive,” Weber said. “And for me, that means moving it forward into the future. We have to have a vision that’s not 10 years old. We have to have a vision 50 years out, 60 years out.”

That includes a partnership with the Sierra Institute to run a state-funded sawmill that will take those burned, skeletal trees that dot so much of Plumas County and churn out mass timber, a much-hyped, eco-friendly source of lumber that’s usable for new wildfire-hardened housing.

Others are looking to tourism, hoping to capitalize on Greenville’s proximity to the Pacific Crest Trail. Kira Wattenburg King, with help from her partner, Plumas County Supervisor Kevin Goss, is working to reopen a sprawling resort with “Dirty Dancing” vibes.

Meanwhile, Kaley Bentz, the third-generation owner of Riley’s Jerky, recently finished building a production facility — much bigger than the one that burned down — that will employ two dozen people.

More than anything, the people from Greenville believe they’re creating a sustainable, climate-change-proof model, not just for their town, but for all of the rural West. And there’s some indication that federal and state officials are paying attention to what they’re doing.

“We care about the individuals and we care about economic development, and they’ve got to be two trains,” Weber said, waving two fingers through the air. “They’ve got to be moving at the same time.”

We harbor no illusions.

We don’t expect anyone in rural Northern California to voluntarily move — assuming they can even afford to do so — simply because climate scientists warn they’re at extreme risk for losing everything in a wildfire. Or because it might be more prudent to invest our finite tax dollars to prevent a disaster in a city or a suburb with more people.

History has demonstrated again and again that the needs of the many do not outweigh the wants of the few or the one. Otherwise, there wouldn’t be wealthy people in Southern California trying to keep their lawns green even as Lake Mead approaches “dead pool” status.

What bothers us — and what inspired us to spend time in Greenville — is that almost no one in the Newsom administration seems to be discussing the overlapping issues of climate change, forest management and housing in a cohesive or comprehensive way.

Even as alarms are sounded about aridification, severe drought stretches into another year with an almost nonexistent snowpack and predictions emerge about a “megaflood” displacing up to 10 million Californians, a statewide land-use plan remains a pipe dream.

Instead of heading off a worsening if undeclared war between urban and rural communities over increasingly scarce resources, we’ve been left with competing public policy imperatives.

The state is spending enormous sums to rebuild mountain towns that have burned down, while also discouraging people from moving into the wildlands where most wildfires happen, while also being slow to crack down on NIMBY cities that have long failed to build enough affordable housing, while also touting its success on combating climate change, while also failing to significantly speed up forest management projects that would reduce carbon-spewing wildfires.

We worry about the consequences if California sticks with this confusing, conflicting mess of a strategy. And if Newsom, in particular, doesn’t get serious about putting the state on a safer, more sustainable path for living in a time transformed by a changing environment. Championing the switch to electric vehicles is important, but so is land use.

Dozens of people have died in wildfires in recent years, with 11 of the deadliest fires occurring since 2000.

Air quality is worsening too. The more than 9,000 wildfires — most of them caused by people — that burned across the state in 2020 shot so much carbon into the atmosphere that it offset decades of gains in air quality, even as the COVID-19 pandemic took millions of vehicles off the road.

And with every wildfire that happens in the Sierra, vegetation burns, weakening slopes and sending sediment into streams and rivers and, eventually, reservoirs, affecting water quality.

Greenville, we should note, is near the top of a watershed that’s used by some 25 million people, including in thirsty Southern California. Perhaps this is why Weber of the Dixie Fire Collaborative speaks about the power of her small town, where crucial questions are being answered and decisions about land use and the distribution of resources are being made.

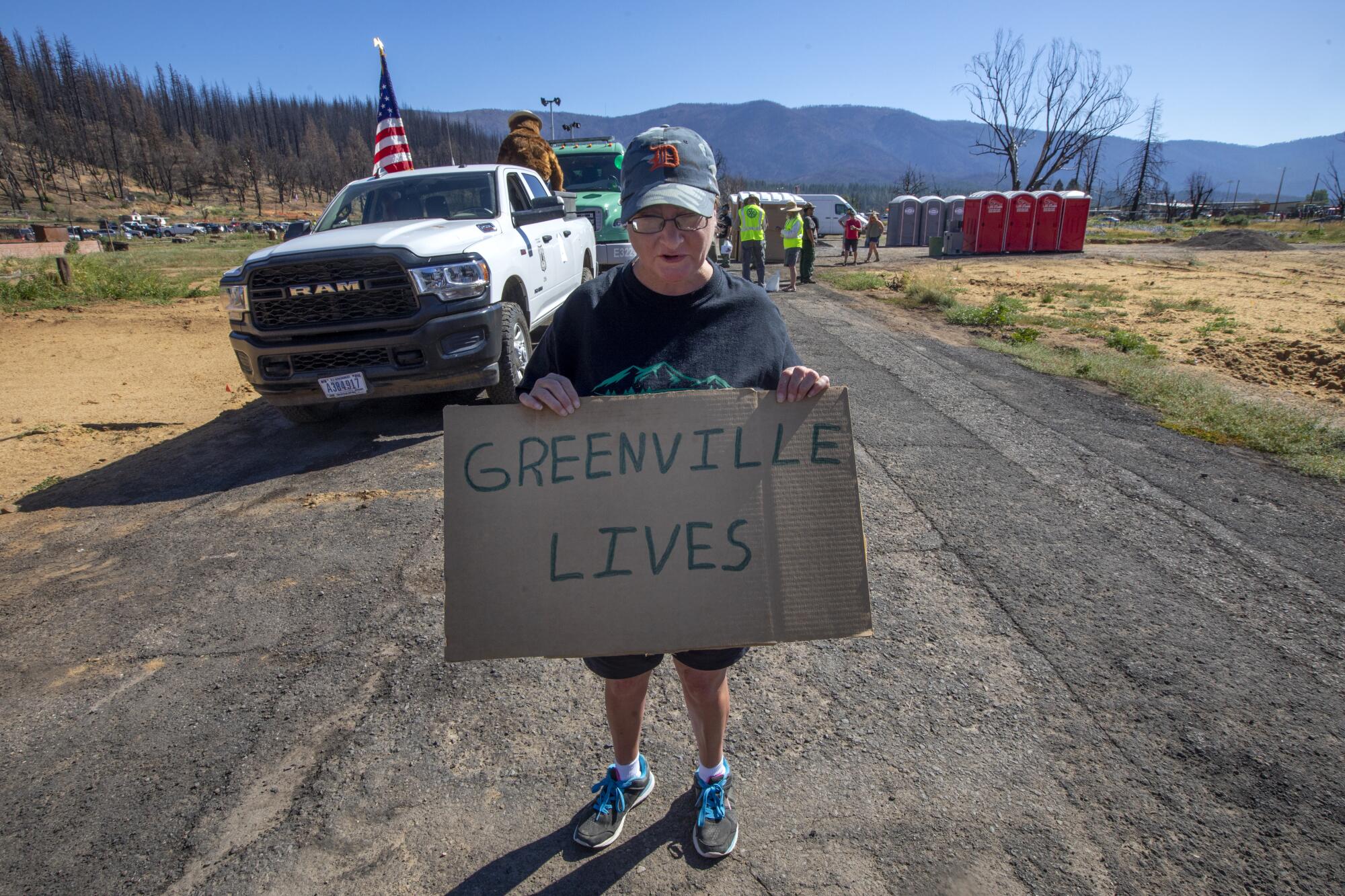

On a Saturday in July, she looked around at the hundreds of displaced residents who had come back to Greenville to celebrate the local holiday, Gold Diggers Day.

A year ago, smoke from the Dixie fire was creeping over the trees and inching across a meadow. Few believed then that flames would roar through the buildings. This year, there was a parade. Drinks and food were served from food trucks, rather than from the usual brick-and-mortar businesses.

“It’s like crazy amazing,” Weber said as she downed the last of a beer from a plastic cup. “A little weird, but amazing.”

A deejay set up. A raucous, drunken dance party followed — in the middle of a burned-down block, in the shadow of skeletal trees, under a sky eerily orange from the setting sun. It amounted to an almost primal scream.

“Greenville lives! We will rebuild!”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.