CARE Court will change how California addresses serious, untreated mental illness. Here’s how

California has a new statewide approach to treatment for people struggling with serious mental illness: the CARE Court.

The program connects people in crisis with a court-ordered treatment plan for up to two years, while diverting them from possible incarceration, homelessness or restrictive court-ordered conservatorship.

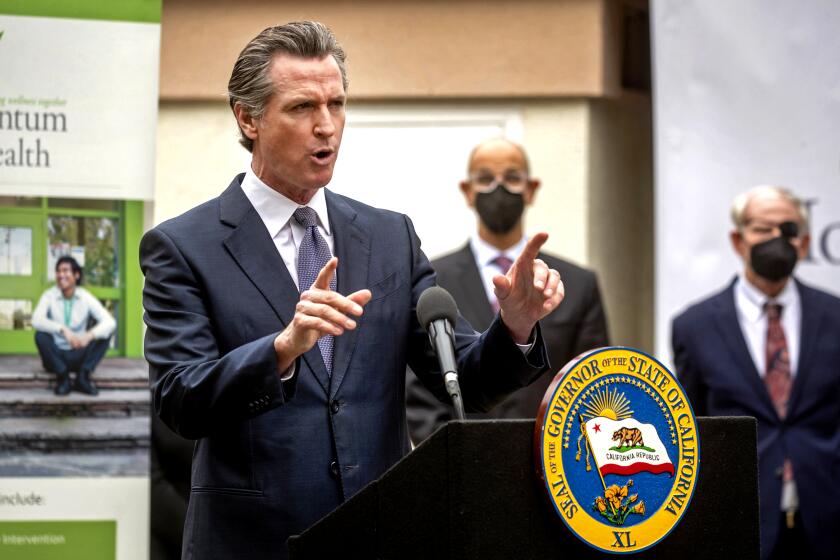

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the measure (Senate Bill 1338) into law Wednesday. Because it does not go into effect immediately, however, most California counties will not see the program’s implementation until 2024.

The law takes a phased-in approach, with Glenn, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, Stanislaus, Tuolumne and San Francisco counties implementing the program by October 2023. The remaining counties are required to start the program no later than December of the following year.

Los Angeles County is poised to join the first wave of counties to launch a sweeping new mental health plan pushed by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

How will CARE Court work?

To initiate a treatment plan, a family member, behavioral health provider or first responder petitions a judge to order an evaluation of an adult with an untreated psychotic disorder (such as schizophrenia) who is in severe need of treatment and, in some cases, housing. A court may also start the program by referring a person from assisted outpatient treatment, conservatorship proceedings or misdemeanor proceedings to a CARE treatment plan.

The judge then orders a clinical evaluation and appoints legal counsel and a volunteer CARE supporter. The supporter would help a CARE recipient understand the options available in the program so the recipient can make decisions with as much autonomy as possible.

Gov. Gavin Newsom signs CARE Court proposal into law, a sweeping plan to order mental health and addiction treatment for thousands of Californians.

If the person meets the criteria, the judge then orders a series of hearings and the development of an individualized CARE plan that’s appropriate culturally and linguistically.

The plan — developed by county behavioral health professionals, the individual and the volunteer supporter — can include behavioral health treatment, medication, substance abuse treatment, social services and housing specific to the individual’s needs.

If needed the court may issue orders necessary to support the CARE recipient in accessing housing and services, including imposing sanctions on providers and local government agencies if they fail to provide court-ordered services or treatment.

Throughout this process, the court will hold status hearings as needed to check in with the recipient and review the progress made, the services provided, any issues the person might be experiencing with the program and recommendations for making the plan more successful.

People who graduate from the program will remain eligible for ongoing treatment, supportive services, and housing in the community to support long-term recovery.

Who is eligible for this program?

The CARE Court program is for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder or other psychotic ailments in that class, as defined by the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

A person struggling with these mental health challenges must also be 18 years old or older and not currently stabilized by treatment. In addition, the person must be deteriorating substantially and “unlikely to survive safely in the community without supervision,” or at risk of a relapse or deterioration that would result in “grave disability or serious harm to the person or others.”

This program may be an appropriate step for someone who has experienced a short-term involuntary hospital hold (either 72 hours or 14 days) or who can be safely diverted from certain criminal proceedings.

As Mexican singer-songwriter Carla Morrison releases a new album and embarks on a tour, she’s talking openly and honestly about her mental health.

Is this program voluntary?

Although participation in CARE plans is voluntary, a court can draw up a plan for a qualified individual without that person’s consent, and a judge can order housing and other services for that person. Some critics of the program, including the ACLU and Human Rights Watch, argue that it’s coercive to force people into court proceedings as a way to provide treatment.

No criminal penalty can be imposed if the person refuses or fails to participate. People who don’t successfully complete their treatment plan will be terminated from the plan, although they will still be entitled to all the services and support for which they’re eligible.

In such cases, a court may use existing authority under the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act to ensure a person’s safety by notifying the county behavioral health agency and the Office of Public Conservator and Guardian.

If all the appropriate CARE plan services were made available but the person didn’t participate, that will affect any hearings held for that person under the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act in the following six months, creating a presumption that the person needs additional intervention beyond what CARE can provide.

Times staff writer Anita Chabria contributed to this report.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.