As Mexican singer-songwriter Carla Morrison releases a new album and embarks on a tour, she’s talking openly and honestly about her mental health.

Carla Morrison stepped away from the spotlight in 2018, 15 years after the Mexican singer-songwriter started performing with her first band, Babaluca.

She had had enough of the persistent criticisms that came with fame. Strangers made cruel comments about her body, tattoos, lyrics, talent and musical style. When she performed, people would boo and flip her off.

“I felt unwanted, like people didn’t want me to exist, and I felt like, ‘They’re right. I shouldn’t,’” she said.

She started having suicidal thoughts.

“They broke mi persona, and I didn’t realize it because I was playing strong,” she said. “I was trying to give this narrative of ‘Yo sí soy fuerte [I am strong],’ but it was hurting me.”

And although she knew many people supported her work, the negative voices grew louder.

“Me sientí muy infeliz [I felt very unhappy],” Morrison said through tears during an interview at her Los Angeles-area home in March.

So she got a student visa to study music in Paris — and moved to a place where nobody knew who she was.

Morrison has been a singer and composer since she was about 20 years old. She’s released three studio albums, has two Grammy nominations and three Latin Grammy Awards. She’s best known for her romantic songs that include “Eres Tú” and “Compartir.”

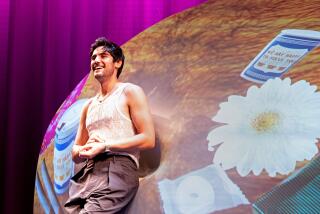

When she spoke to The Times recently, she was preparing to open for Coldplay in Monterrey, Guadalajara and Mexico City and was due to begin rehearsing for her upcoming tour, when she will perform in 19 cities, including a Thursday appearance at the Greek Theatre in L.A.

But before these recent career milestones, she took a three-year break from writing songs. When she started making new music again, the songs centered around her mental health. Her single, “Ansiedad (Anxiety),” the first song she released after her hiatus, is about the anxiety she’s dealt with since she was a kid.

En el viaje, perdí mi verdad

Siendo una estrella dejé de brillar

(In the journey, I lost my truth

Already being a star I stopped shining)

2020 brought more challenges — the pandemic, the death of her father, moving to Los Angeles and a new phase of her mental health journey. The songs she wrote during this period would become “El Renacimiento (The Renaissance),” the album she released April 29.

Carla Morrison on her music

“Este Soledad” (2010)

“That was one of the songs that I felt was a cry for help for me.”

“Suciedad” (2010)

“‘Suciedad’ was actually about my sexual abuse ... when I was a kid and how that tormented me. A lot of people don’t know that it talks about that.”

“Todo Pasa” (2015)

“It was talking about how I felt about fame and how I felt just very sad and lonely — that fame was a very lonely place to live in.”

“Ansiedad” (2022)

“It was addressing how my anxiety has been with me for the longest time.”

Morrison said she’s always been a sensitive person. As a preteen, she started having anxiety and panic attacks. It wasn’t easy for her to ask for help, but she knew she needed to talk to someone other than her family. She later realized she had trauma from being sexually abused when she was 5.

“I was having these horrible, horrible thoughts, thinking my parents are going to hate me for life,” she said. “I’m a disgrace to this family because I brought this upon me.”

Despite her fears, she asked her mother if she could see a therapist. “Por qué mija? Pero tú no necesitas ir a un loquero,” was her mom’s first reaction. (“Why, honey? You don’t need to see a shrink.”)

She told her mom that if she didn’t see a doctor, she was afraid of where her uncontrolled anxious and depressive feelings might lead. Morrison got the help she needed.

Decades later, therapy has helped her understand that the abuse wasn’t her fault, that she deserved love. She overcame trust issues and learned to use her art as a creative outlet.

“I wish not only in Mexico, but in Latin America, we would talk [about our struggles] as much as we talk about the good things,” she said. “We should talk about the bad things in a more responsible, empathetic and compassionate way.”

Morrison credits being honest about who she is and integrating that new outlook into her music to living in Paris and getting away from the spotlight.

“Siempre pensé que podría ser honesta conmigo sobre mis emociones, o sea, como auténtica como en mi persona, siempre siente que podía ser lo. Creo que me empecé siente mal cuando siente que ya no pueda ser lo,” she said. (“I always thought I could be honest with my emotions, I mean, authentic with myself. I always thought I could do that. I think I started feeling bad when I felt that I couldn’t do that.”)

The pace of the Parisian lifestyle was healing. She relearned to sit down for coffee without her computer, take photos for herself and not for Instagram, spend time with her husband and dogs and people watch.

“When I arrived, I remember feeling like, ‘Man, these people are so slow,’ and then I realized: No, I’m actually going so fast, and there’s no need to go this fast the whole day,’” she said.

Morrison started getting famous in the 2000s, but she said after “a certain thousand followers, it started to get very dark.” With the fame came the daily pressure she put on herself to live up to others’ expectations, and the anguish when she felt she didn’t.

“It was just like ‘Oh wow, I’ve been so bad to myself,’” she said.

But in Paris, she remembered walking beside the river, crying for hours, and never feeling judged. “It was just nice to feel so free,” she said.

Stories and advice about Latino mental health

As some pressures faded, though, the pandemic weighed on her.

In 2020, Morrison’s father died of COVID-19.

“I was just so worried about him because he died by himself ... and it was something that I couldn’t let go,” she said.

She and her husband decided to move from Paris to Los Angeles. They went from feeling like students — learning French, listening to jazz, eating cheese and drinking wine — to being swamped again with work responsibilities and having to confront reality.

“It was hard at a point where I started to feel very sad again,” she said.

Everything she had been doing to manage her mental health suddenly wasn’t working anymore. She started looking for help again, researching ketamine as a treatment for depression, PTSD and anxiety disorders.

She scheduled a treatment, but not without trepidation: “I was like, ‘I’m so scared. I don’t even smoke weed, man.’”

But: “I remember coming back home [after the first session], and the first thing I noticed was that I wasn’t sad anymore and that I wasn’t scared. I knew where that fear came from,” she said.

First generation trauma is an emerging term in the Latino community, with people talking about it on social media. Here’s how it affects children of immigrant parents.

The ketamine was another way to help slow her down, she said. It helped her relax and access parts of her subconscious that she was still resisting during her therapy sessions. She started to understand where a lot of her anxieties came from. She was able to better process her dad’s death.

“To me, it’s been a journey of all my life,” she said. “Therapy sessions, the ketamine, moving in and out of countries and trying all sorts of different therapies and just really looking for answers to all of my questions,” she said.

It’s still hard for her to think about all the pain she’s endured and the criticism that comes with being in the public eye.

It’s not that she wants everyone to love her, she said.

“I just don’t want them telling me that I’m fat constantly, that I’m stupid, that I’m untalented or that I have no identity,” Morrison said.

She’s heard people say, “Well you signed up for this. Tú querías esto [You wanted this].” But Morrison disagrees. She just wanted to make her songs.

People have also told her, “Well, you have to take it.”

No, she’d rather talk about it.

In 2021, Morrison started Martes de Ansiedad (Anxiety Tuesday), a virtual conversation with her fans through Instagram Live.

She’ll often kick off the conversation by sharing an example of her anxieties. She’ll point to an “ask me a question” box where anyone can leave a question or comment.

Morrison is careful not to give medical advice, but she’ll talk about what helps her when she gets anxious in the beginning of the week, looking at the workload ahead of her. It’s a place where her fans can feel safe to ask questions about their own struggles — or how to help their loved ones who have anxiety.

“Me llegan tantas, tantas solitaciones y commentarios que digo, ‘Wow. Que fuerte que no hablamos de esto,‘” Morrison said. (“I get so many messages and comments that I say, ‘Wow. How powerful it is that we don’t talk about this.’”)

She wants to validate other people’s experiences, whether they’re struggling with abuse, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation or grief. She wants people to be brave and love themselves enough to try other methods of mental health treatment if they need it, no matter what others might think.

She wants people to know they’re not alone.

In “No me llames,” her second single off of “El Renacimento,” she sings about pushing away the negative voices.

Hoy que ya no estás

Pude descrifrar

Tú eras la mentira

Yo era tu verdad

(Now that you aren’t here

I could decipher

That you were the lie

And I was your truth)

“Honesty will give you freedom, and freedom will just give you peace,” she said.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.