Newsom departs from his liberal image with controversial wins at the Capitol

SACRAMENTO — In a subtle departure from his national image as a liberal champion, Gov. Gavin Newsom successfully pushed state lawmakers to support a series of tough policies in the final weeks of the legislative year that bucked progressive ideals and ultimately could broaden his appeal beyond California.

Democratic and Republican lawmakers at the state Capitol heeded his call to extend operations at Diablo Canyon, reversing an agreement environmental groups drove six years ago to shut down California’s last remaining nuclear plant out of safety concerns.

The governor won support for his plan to provide court-ordered treatment for unhoused Californians struggling with mental illness and addiction amid outcry from powerful civil rights organizations.

Newsom vetoed legislation to allow supervised drug injection sites in pilot program cities, drawing criticism that his decision was politically motivated as speculation swirls around his prospects as a potential presidential contender.

“He is making political calculations on all of these decisions in a very deep and nuanced way that considers where he wants to go next,” said Mary Creasman, chief executive of California Environmental Voters. “That doesn’t mean he doesn’t care about these issues. I think he does. He’s making political calculations around how to still move the needle for climate while also protecting some of the political interests.”

Newsom successfully lobbied the Legislature to approve a $1.4-billion forgivable loan for Pacific Gas & Electric in order to continue operations at Diablo Canyon through 2030. He said the bill was critical to the state’s ability to avoid rolling blackouts during heat waves, which have caused problems for California and presented political challenges for the governor. Newsom signed that legislation into law Friday.

He balanced the controversial ask with a package of bills to address climate change that Creasman and other environmentalists celebrated.

The marquee policy in Newsom’s climate package, which he announced just weeks before the end of the legislative session, created health and safety buffer zones between homes, schools and public buildings and new oil and gas wells. That also squeaked by this session after lawmakers had tried — and failed — to pass those restrictions for years without his intervention. Other more contentious legislation addressed carbon capture technologies, which some environmental organizations argue only perpetuates oil extraction.

“That was 100% strategic,” Creasman said. “It’s strategic because he wants the headlines to be about climate action versus about these other things he’s doing, which I get. But he’s doing both. The authentic story is both. There were some really phenomenal things and there were some really tough things.”

Newsom pressed for the climate legislation amid a clash with the oil industry that drew national attention. As part of a campaign to call out Republican governors and make himself a resonating voice for Democratic voters across the country, Newsom ran ads in Florida contrasting that state’s restrictive policies on abortion rights and education with California’s more liberal positions.

Western States Petroleum Assn. responded with its own advertisements in Florida warning about the cost of Newsom’s climate policies.

Creasman said being seen as a climate leader is smart if Newsom has national ambitions. Though the term “climate change” has been politicized, voters nationwide want the government to do more to mitigate increasing drought, wildfires, pollution and extreme heat. It’s also the only issue that will give Newsom a global spotlight, she said.

Since his sound defeat of the Republican-led recall attempt last September, advisors to Newsom have said his decisions are less motivated by politics and are instead a reflection of the confidence he feels to govern in a more nuanced way. The strong support he received from the electorate gave him the freedom to stray from a strictly progressive agenda that many in his party want him to follow.

In an interview with The Times in July, Newsom said that his first term has gone by in a flash and that he wants to take advantage of the time he has left.

“If I’m privileged to have a second term, you guys will be writing my obituary within six months and who’s the next person coming behind me,” Newsom said. “I know how limited my time is and I just don’t want any regrets. I don’t want to look back and join some panel of ex-governors saying, ‘I woulda, coulda, shoulda.’ I’m not going to do that.”

Robin Swanson, a Democratic political strategist, said Newsom’s also practicing “pragmatic politics.”

She compared his legislative approach to that of former Gov. Jerry Brown. When Brown returned to the governor’s office in 2011 for his third term, he was a more seasoned politician with less adherence to a strict political ideology.

“I think this is part of his growth as governor,” Swanson said. “When you’re managing a state of 40 million people, you have to do what matters and what works in that moment whether that aligns 100% with what you would do in a perfect world. Those solutions often are a little more center, more middle of the road.”

Newsom disappointed many of his allies last month when he vetoed Senate Bill 57, legislation to allow Los Angeles, San Francisco and Oakland to set up supervised injection site pilot programs. Moderate Democrats and Republicans, who characterized the bill as government authorization to use lethal drugs, applauded the decision. They urged Newsom to pour more resources into treatment and rehabilitation programs instead.

But advocates and addiction specialists said the veto would lead to more deaths amid an opioid overdose crisis.

Mike Herald, director of policy advocacy for the Western Center on Law and Poverty, said the governor’s rejection of the bill was disappointing because it seemed like the type of first-in-the-country bold action he gravitates toward.

Herald also suggested hewing toward the middle is not new for Newsom. While he was a county supervisor and then mayor of San Francisco, Newsom championed Care Not Cash, a policy to reduce welfare for single homeless adults and instead spend the funds on shelters, housing and services.

“I’m just not as surprised as some when he’s more conservative-leaning on certain issues,” Herald said.

Newsom also faced fervent opposition from civil rights groups for his Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Court proposal, a far-reaching plan to provide court-ordered treatment for thousands of Californians suffering from a mix of severe mental illness, homelessness and addiction.

A coalition that included the American Civil Liberties Union, Disability Rights California and the Western Center on Law and Poverty — groups with which Democrats in the Capitol often align — spent the legislative session castigating the proposal as an inhumane effort to criminalize homelessness and strip people of their personal freedoms. The Legislature overwhelmingly approved it, with Republicans and Democrats celebrating its passage.

“It runs completely counter to truly progressive ideals,” said Susan Mizner, director of the ACLU’s Disability Rights Program. “It’s a throwback to an era in which we punish people for being poor and we punish people for having mental illness.”

Homelessness and crime were among the top three concerns for California registered voters in a UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll conducted this spring, and Newsom is well aware of the potential political liabilities he faces if he fails to address those issues.

Despite the criticism from the left, Newsom isn’t expected to face much, if any, retribution from California liberals when he comes up for reelection in November. A recent poll found that Newsom led his challenger, state Sen. Brian Dahle (R-Bieber), by more than a 2-1 margin. Many of the conservative Republican’s policy positions, including his opposition to abortion rights and government mandates of COVID-19 vaccinations and restrictions, are denounced by Democrats.

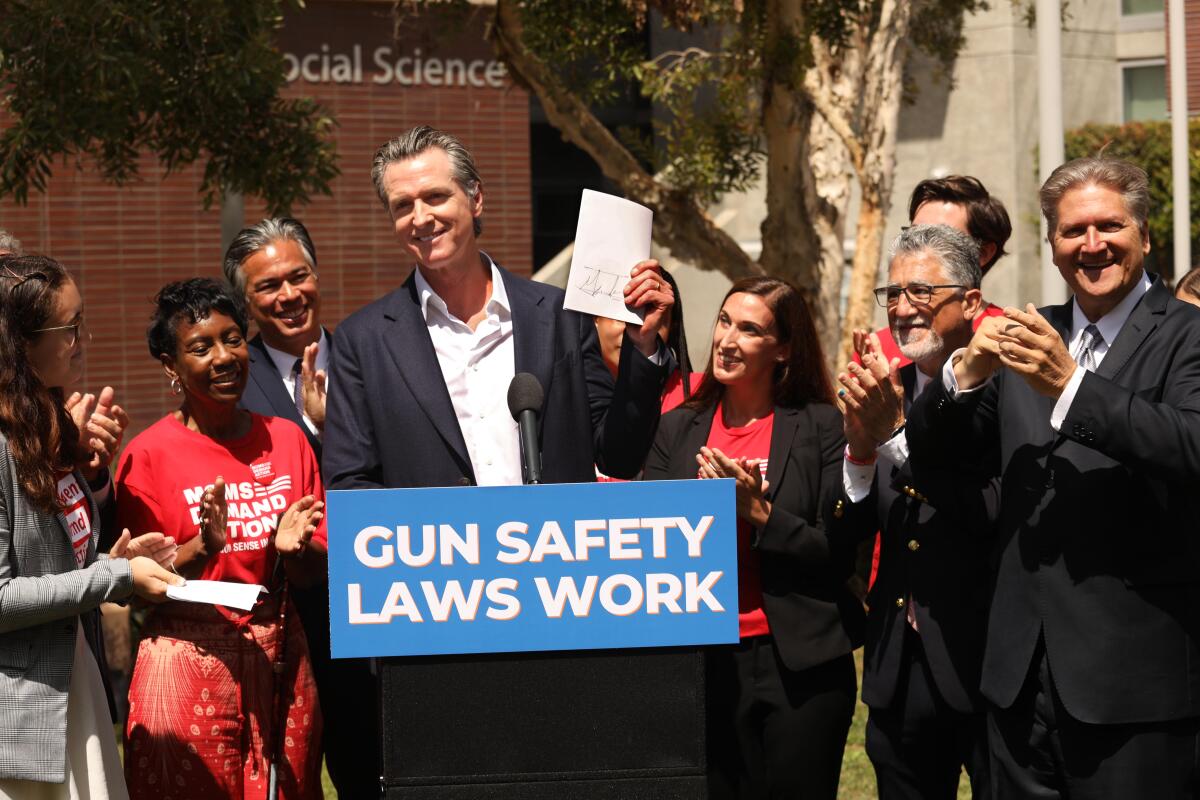

Newsom and Democratic lawmakers this year did notch big wins on gun control legislation, an issue embraced by the left, after a wave of mass shootings this spring and summer shocked the nation.

Newsom and legislators pledged swift action on more than a dozen gun control bills, including one modeled after Texas’ vigilante abortion law that will allow private people to sue anyone who imports, sells or distributes illegal firearms in California. Nearly every measure passed, and Newsom has already signed the majority into law.

But Newsom couldn’t win over enough state lawmakers to pass a concealed-carry proposal. He made national headlines in June when he introduced the legislation alongside California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta and state Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-La Cañada Flintridge) in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling against restrictive open-carry laws in New York, California and other blue states.

Senate Bill 918 would have designated dozens of places as “sensitive,” meaning off-limits to carry firearms, and added new licensing criteria to determine whether applicants presented a danger to themselves or others. The proposal fell two votes shy of passage early Thursday morning, after several moderate Democrats either abstained or voted against the measure.

“He wants to be a player in national Democratic politics,” said Jack Pitney, a professor of American politics at Claremont McKenna College. “He also has to attend to the mundane business of running California. And both of those things are on his mind.”

Newsom surely remembers what happened to the last blue-state governor who won the Democratic presidential nomination, Pitney said. Michael S. Dukakis took positions that looked good in Massachusetts but made him vulnerable to GOP attacks in the 1988 presidential race.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.