California hopes to fight global warming by pumping CO2 underground. Some call it a ruse

It’s an emerging technology that climate experts say can prevent billions of tons of greenhouse gases from entering Earth’s atmosphere.

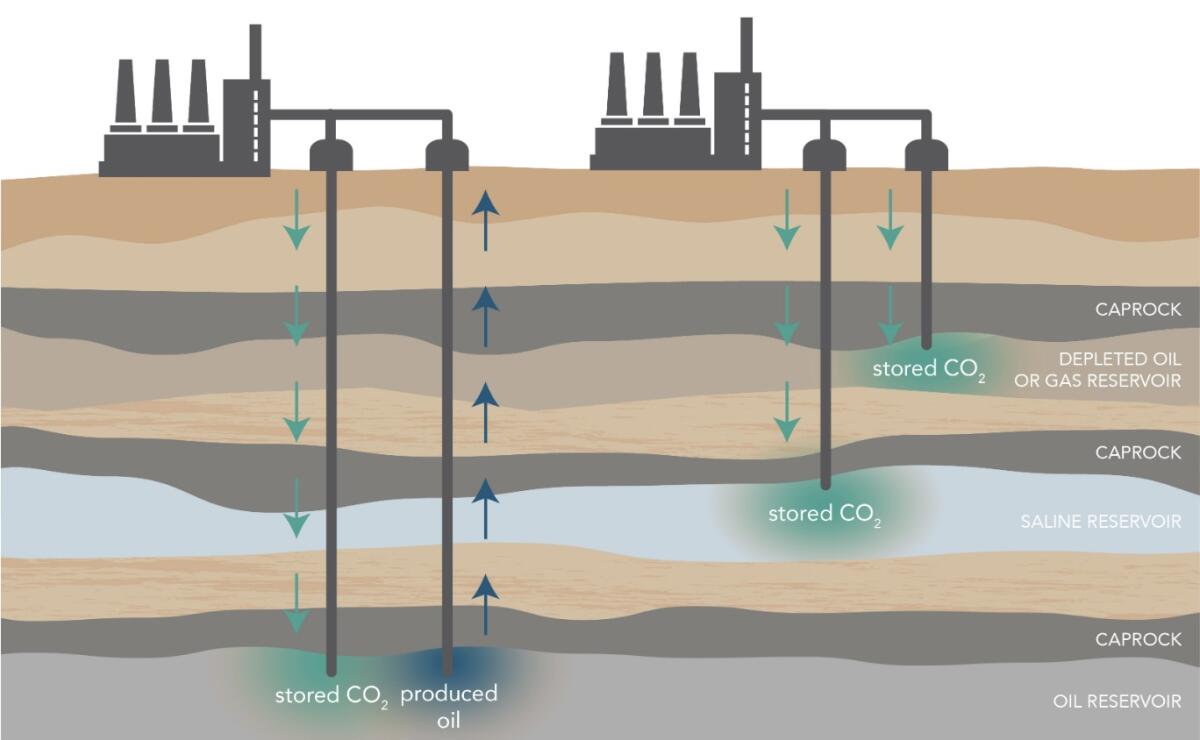

By capturing carbon dioxide as it spews from oil refineries, power plants and other industrial smokestacks and then forcing it deep underground for storage, humanity can reduce fossil fuel emissions while developing alternative energy sources, advocates say.

Now, as California attempts to meet ambitious climate goals, environmental officials are embracing carbon capture and storage, saying the state cannot achieve carbon neutrality without it.

But as officials prepare to finalize a state climate plan that relies on CCS technology, some environmentalists are urging officials to abandon the idea. Instead of helping to wean California off fossil fuels, they say CCS will actually increase oil production.

By forcing pressurized carbon dioxide into old wells, drillers can flush out crude that would otherwise remain beyond their reach. At the same time, oil companies can claim tax incentives and avoid financial penalties for mitigating their greenhouse gas emissions.

“If we are truly committed in California to a just transition off of fossil fuels, we should not be looking for ways to perpetuate oil extraction in old oil fields,” said Catherine Garoupa White, executive director of the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition.

The debate over how this technology could be deployed may prove to be a reckoning for California, a state that has long wrestled with its role as a global leader in the fight against climate change and its status as one of the nation’s top oil producers.

Already, regulators are considering more than a dozen CCS proposals that would store millions of tons of carbon dioxide beneath California’s Central Valley — the only region of the state considered practical for such storage. At least one of those proposals would be used to enhance oil production in Kern County.

An increase in catastrophic wildfires has reduced California tree cover by 6.7% since 1985, and researchers fear the lost trees will never grow back.

The state climate plan, which will be finalized by the California Air Resources Board this fall, is silent on the use of CCS for oil production. The staff-recommended proposal calls for more than 220 million tons of carbon emissions to be stored underground in the next two decades.

Critics of the plan worry it could derail Gov. Gavin Newsom’s goal of ending all fossil fuel extraction in California by 2045.

“Because there’s nothing in the plan that talks about shutting down refining capacity or sunsetting these operations, the concern I’m hearing from people — and I think this is a legitimate concern — is that this could start us down the path of major CCS projects that lock in fossil fuel infrastructure rather than transition it responsibly to a different direction,” said Danny Cullenward, policy director of CarbonPlan, a California nonprofit that analyzes climate solutions.

Others, however, see no other way for the state to meet its climate goals. State law requires California to cut emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. A 2018 executive order by then-Gov. Jerry Brown targeted 2045 to achieve statewide carbon neutrality — the point at which all carbon dioxide emissions released by human activity are equal to the quantity of emissions that are removed from the atmosphere by natural and technological means.

Even as the state continues to incentivize the trade-in of gas-powered cars for electric vehicles, and hastens the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, proponents say carbon capture and storage will be needed as a bridge to offset emissions in the interim.

“The math doesn’t work without it, to be as succinct as possible,” said Virgil Welch, executive director of the California Carbon Capture Coalition, a consortium of CCS advocates, mostly from energy companies.

“We want to pursue strategies like carbon capture to cut emissions to support California’s climate goals,” Welch said. “And there are large portions of the environmental community that are effectively saying, ‘No thanks. We don’t want you to do that,’ which to me is mind-boggling. If you step back and think about it, you’ve got industry saying we want to reduce emissions.”

As San Joaquin Valley growers set fire to uprooted vineyards and orchards amid the worsening drought, residents complain of increased air pollution.

While the state plan suggests CCS will account for only a small portion of greenhouse gas reductions, the Air Resources Board says it is essential to curtail emissions in such processes as cement manufacturing — operations that cannot be electrified and powered by renewable energy. The state climate plan also calls for this technology to be installed on a majority of state oil refineries by 2030, in an effort to curb emissions while still meeting local demand for gasoline and diesel.

But this would probably require billions of dollars in investments to install equipment that would siphon carbon emissions from smokestacks and build a network of pipelines from Los Angeles and Bay Area refining hubs to the Central Valley.

In addition to the considerable costs, some public officials have raised concerns about possible leakage from pipelines and injection sites in an earthquake-prone state.

“I think we have to tip the balance to more direct emission reductions,” said Davina Hurt, a member of the Air Resources Board, at a meeting last month. “Leakage is a real issue. There’s major capital involved. And I’m concerned that we’re unwittingly extending the life and production and consumption of fossil fuels.”

Among those proposing CCS projects is California Resources Corp., an oil and gas company headquartered in Long Beach.

California Resources has proposed capturing 1.5 million tons of carbon dioxide annually from its Elk Hills natural gas power plant about 20 miles west of Bakersfield. That’s roughly the amount of carbon dioxide that 300,000 cars will produce in a year.

The carbon dioxide would then be pumped into California Resources’ Elk Hills oil field to produce 51 million more barrels of oil over two decades, according to company estimates.

By injecting carbon emissions into its Kern County wells, the company can “effectively reverse the recent decline of oil production,” according to a government-funded study of the project.

The company — the state’s largest nongovernmental landowner — has said its efforts could lead to the first “net-zero” barrel of oil in California. However, conventional operations that use carbon dioxide to displace oil offset only 40% to 50% of emissions per barrel.

“As we envision a net-zero future, it will be necessary to leverage low carbon solutions, including more sustainable and emissions-free fuel,” company spokesman Richard Venn said.

The company has also proposed a multiphase project called Carbon TerraVault, which would store carbon dioxide from other industrial facilities. It would not be used to enhance oil extraction.

Although international climate authorities have urged the rapid scale-up of CCS systems worldwide — saying they are a crucial tool in limiting global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius — use of the technology has lagged.

Since the first carbon capture and storage facility began operations in Norway in 1996, only 26 others have been deployed globally. The systems now sequester 40 million metric tons of carbon emissions a year — a far cry from the 1.7 billion metric tons international officials want to see by the end of this decade.

One of the main challenges to ramping up production has been the cost of equipment needed to capture and pressurize carbon dioxide, as well as the logistical hurdle of transporting the material to a storage site. The virtually liquified gas can be conveyed either through pipelines or via trucks or train.

Nationally, 29 of the top 30 counties with the highest level of particulate pollution in 2020 were in California, researchers say.

A 2020 analysis by Stanford University identified more than 70 potential carbon dioxide capture sites across California, including facilities that refine crude oil into gasoline, diesel and other petroleum products. Most of the facilities were concentrated in Los Angeles or the Bay Area, which would require the construction of more than 100 miles of pipeline to reach the Central Valley — the safest region in the state for carbon emissions to be stored and the least susceptible to earthquakes, experts say.

Currently, there are only two pathways to finance such an undertaking: massive government subsidies or allowing private industry to fund these projects by linking them to oil wells that will produce crude, says CarbonPlan’s Cullenward.

“There is no commercial value to sticking CO2 into the ground,” Cullenward said. “The only value comes in avoiding penalties or fees, or the tax incentives that are designed to do that. But those are public policy incentives. There’s no private commercial rationale to do it.”

Eleven of 12 large-scale carbon storage facilities in the United States use captured carbon dioxide for oil production, according to a 2021 report from the Global CCS Institute, an industry group that tracks these facilities.

As almond growers use increasingly scarce and expensive water to irrigate this year’s crop, over a billion pounds of nuts remain stranded in port.

State Sen. Monique Limón (D-Santa Barbara) is sponsoring a bill that would ban using carbon storage projects to produce oil in California. She is not opposed to the technology; however, she believes it will be harder for California to meet its climate goals if carbon emissions are used to induce higher rates of oil production.

“If carbon capture is intended to be a climate strategy, it should not be in the business of creating more fossil fuels,” Limón said.

Limón and other critics note also that CCS technology would do little to reduce environmental harms suffered by those who live in the shadow of oil refineries.

Although the technology removes carbon dioxide, it would not eliminate cancer-causing benzene, smog-forming nitrogen oxides or particulate pollution that refineries emit.

That concerns Alicia Rivera, an organizer with Communities for a Better Environment. She said Los Angeles-area residents who live near refineries in the South Bay and Harbor region will continue to contend with harmful pollution, despite reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

“Wilmington will continue to be the hot spot and sacrifice zone. And there is no way out,” Rivera said. “New generations are going to have to endure the effect of what is already in the air. Carbon sequestration paints a very grim picture for communities that are in the front line of the fossil fuel.”

More to Read

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.