‘Shocking’ Tom Girardi scandal shows need for legal reforms, California chief justice says

The private judging industry needs stronger oversight, California’s chief justice said, following a Times report last week on the role for-hire judges played in Los Angeles attorney Tom Girardi’s suspected swindling of clients out of millions of dollars in settlement money.

Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye called revelations about the conduct of the retired judges, including a former state Supreme Court justice, “shocking” in a statement to The Times, acknowledging, “There are not adequate safeguards regarding the business of private judging.”

A Times investigation draws on newly revealed records about Tom Girardi’s legal practice, opening a window onto the secretive world of private judges.

For decades, Girardi paid well-regarded private judges as much as $1,500 an hour to help him administer mass tort cases involving thousands of clients. The Times described how Girardi traded on the names of these former jurists to deflect questions about missing money and how, in some instances, they aided his misappropriation of client funds.

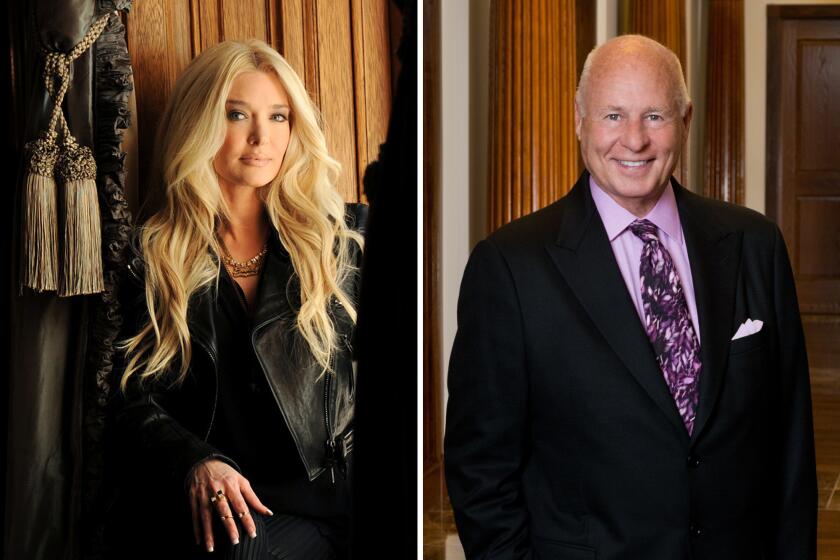

In one settlement in which a former appellate justice was paid $500,000 to oversee the distribution of funds, Girardi managed to divert millions of dollars from a settlement account for questionable purposes. A downtown jeweler received $750,000 for what court records show was the purchase of diamond earrings for Girardi’s wife, Erika, of “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” fame.

Retired jurists serving as arbitrators and mediators hold an increasingly important and powerful place in the legal system, but their work occurs mostly behind closed doors and is rarely scrutinized by outsiders. Sitting judges answer to the state Commission on Judicial Performance, but private judges are not subject to regulation by a specific government agency.

The murky provenance of high-end jewelry and the earrings that became a plot point in the downfall of high-flying lawyer Tom Girardi, husband of “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” reality star Erika Jayne.

The State Bar of California theoretically has jurisdiction over private judges who maintain their law licenses, but the agency acknowledged Monday that it was “not aware of any prior investigations” of them. “There does not appear to be an overarching regulatory framework for private judging or mediation,” the agency said in a statement.

Cantil-Sakauye, the chief justice, lamented the “multifaceted victimization of injured people” in the Girardi case. She did not offer a specific course of action to protect the public but suggested that lawmakers in Sacramento should take the initiative.

“I believe the Legislature is the proper authority to regulate the conduct of the mediators,” said Cantil-Sakauye, who announced last month that she plans to retire when her term ends in January.

Bankruptcy trustees have accused the reality star of concealing assets for her husband and are dispatching investigators to comb through her belongings and accounts.

Some in Sacramento say they are prepared to act.

“If I’m reelected, there will be hearings, and there will be legislation,” said State Sen. Tom Umberg (D-Orange), chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

He labeled The Times’ findings “stomach-churning” and said, “It’s pretty clear to me that something needs to be done.” Among legislative measures, Umberg floated the possibility of mandatory disclosure of past relationships by an arbitrator or mediator.

Girardi repeatedly drew on the high-priced services of retired jurists affiliated with Irvine-based JAMS, the nation’s largest private arbitration and mediation firm. They included JAMS co-founder and former chief executive John K. Trotter Jr., a retired California appellate justice, and former state Supreme Court justice Edward A. Panelli.

The Times described Panelli’s role in a $17-million settlement Girardi secured for elderly women who alleged they got cancer from a menopause drug. When some of the women suspected in 2014 that Girardi had not paid them all they were due, his firm blamed Panelli and said the retired justice had ordered them to “hold back” $1 million. The claim was false, but the jurist did not inform the clients or the trial court and fought a subpoena for months before finally being forced to testify under oath. Only then did Panelli disclose that Girardi was lying.

Times reporting has played a starring role in ‘The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills’ this season. Here’s our guide to Erika Jayne and Tom Girardi.

Trotter, the former justice turned JAMS executive, also worked on settlements in which clients accused Girardi of stealing money. In a $66-million settlement with the maker of the diabetes drug Rezulin, Trotter was appointed in 2005 as the “special referee” overseeing the distribution of money to clients, as well as to Girardi and other lawyers on the case. In the years that followed, more than $15 million went to Girardi’s jeweler, for the diamond earrings, and his firm, for supposed expenses. Experts who reviewed financial records for The Times said the pattern of payouts indicated fraud.

Both Panelli and Trotter declined interview requests about their dealings with Girardi. In statements, they said they had limited roles that they carried out ethically. Asked to address the chief justice’s comments, JAMS (formerly known as Judicial Arbitration and Mediation Services) reiterated a previously issued statement that its roster of former judges “are expected to adhere to the ethical standards that they swore to uphold under oath.”

The outgoing chair of the Assembly Judiciary Committee, Mark Stone (D-Scotts Valley), agreed that the private judges’ dealings with Girardi were evidence of an unaddressed problem.

“The fact you have judges with long-standing relationships with an attorney like Tom Girardi and doing things to his benefit and their own personal benefit — there is not currently a structure to hold anybody in those circumstances accountable,” said Stone.

Clients who have accused Tom Girardi of misconduct will be tracking the new season of ‘Real Housewives,’ hoping for evidence to bolster their case.

Stone, who is retiring this year, said he was skeptical of a legislative fix to the problem, given opposition to prior proposed legislation to bring more transparency and public safeguards to the arbitration industry. Those measures, he said, were vigorously contested by corporations and business groups that favor the system that allows them to settle disputes out of public view, adding, “I’m not sure these ethical lapses bother them that much.”

“Those are very, very difficult bills to get through the Legislature, because those who stand to benefit from the way the arbitration system works oppose us at every turn, and that is to the detriment of consumers,” Stone said.

A longtime critic of the private judging industry, former Santa Clara University School of Law Dean Gerald F. Uelmen, said it seems reasonable to regulate the private judging industry, but advocates should expect strong opposition from sitting judges, some of whom see private judging — with its cushy salaries — as a retirement plan.

“After years of working ... for just barely reasonable compensation, when they retire, they kind of strike it rich, and they like it,” said Uelmen. “A lot of them are eager to retire and move on to that richer realm — so I think part of the opposition will be from judges who want to do it and see it as a just reward for all their years of hard work.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.