California used to pay people to hunt mountain lions. Now we spend millions to protect them

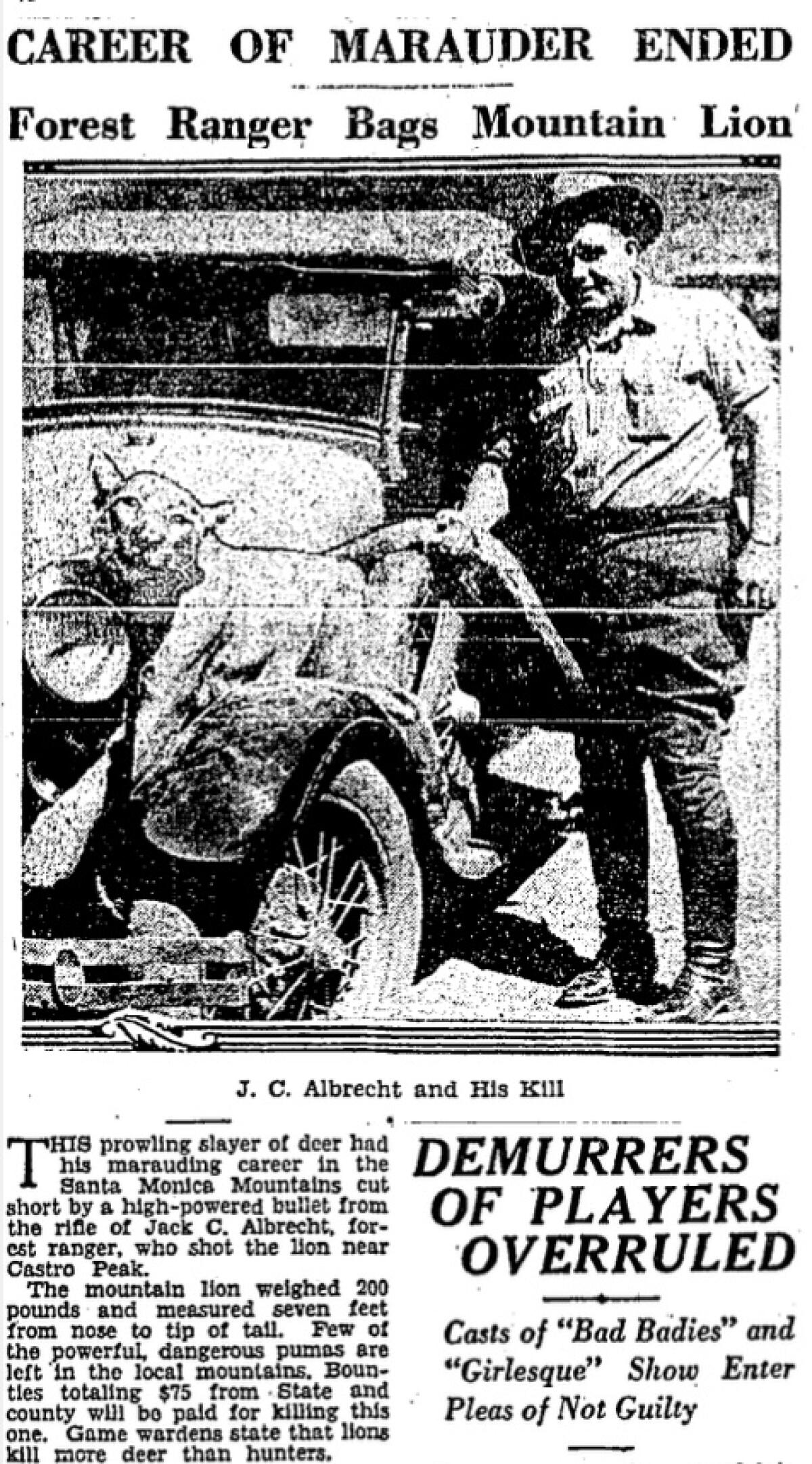

Whoever drove the car or truck that last week killed the mountain lion P-89 on the 101 Freeway in Woodland Hills — about 60 years ago, that driver would have been in line for a reward, a government atta-boy bounty of as much as $75 (more than $730 today).

California was not fussy about how you killed a mountain lion, just so long as you did. Over nearly six decades, from 1907 until 1963, the state paid out more than half a million dollars for 12,461 mountain lion corpses.

Today, we mourn publicly when even one Felis concolor is killed by human hands or, as happens far more often, by tires.

P-22, the most famous Hollywood feline since the MGM lion, is a beloved pop culture phenom, the alpha cat of an apex species. He has survived rat poison. He has been caught and treated for mange and freed to flaunt his handsomeness around Griffith Park. He is the star of songs, of artwork, of T-shirts and an ugly Christmas sweater. He is the subject of at least two books, one called “The Cat That Changed America” — changed it so much, at least the Southern California part of it, that private donations small and very large make up most of the $90-million “kitty” for a wildlife crossing being built over the “death zone” 101 Freeway that had locked mountain lions into confined habitats.

The crossing is named for ardent animal lover Wallis Annenberg, who, with her family foundation, donated $25 million to build it. Hours before the groundbreaking in April, another mountain lion, P-97, was hit and killed not far away, on the San Diego Freeway.

And in the Legislature, the same state that paid out bounties for dead mountain lions is looking over a bill that could build at least 10 more wildlife crossings across California.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

In the 30 years between 1960 and 1990, the mountain lion went from being a “predator” with a bounty on its head — poisoned, shot, caught in fanged traps, hunted with dogs — to a permit-only trophy-hunting animal to a special protected mammal. In sum, the fewer mountain lions that were left, the more protections they began to get.

How did it happen? How did a creature despised as a pest and a varmint, whose slaughter was once cheered and officially rewarded by California, become a darling and an icon?

Mountain lions, like wolves, were miscast in our Western sagas as savage and indiscriminate killers. In fact, they’d rather give humans a wide berth, except where humans have served up a menu of livestock: sheep, cattle — a captive, easy-prey buffet compared with the mountain lion’s usual chase-and-catch deer entrees.

Hunters had many reasons to shoot first. Kill it before it kills you or your livestock; kill it for its handsome pelt and head or the bounty it brought; or kill it because humans, not mountain lions, had first rights to kill deer.

The Times made this argument several times, perhaps most cold-bloodedly in 1925: “Nowhere have students of animal life found mountain lions doing any good, unless to prevent deer from increasing unduly, and in California that is the special privilege and prerogative for which the sportsman-hunter pays his dollar license.”

Unprovoked attacks on humans by healthy mountain lions were rare enough to make the newspapers. In 1901, Forest and Stream magazine defended the reputations of North American wolves and mountain lions: “There are no such things as dangerous animals; there are creatures which may be made dangerous. The wolf, the bear and the cougar are far more anxious to get away from man than man is to get away from them. ... And yet from day to day, the newspapers continue to print bear stories, catamount stories and wolf stories, and probably will do so until long after the last bear, catamount and wolf have disappeared from the land.”

“Catamount” is a wonderfully exotic synonym for mountain lion.

A legendary attack on humans happened in July 1909, in the Santa Clara County town of Morgan Hill, by an apparently rabid mountain lion.

Three boys were playing in Coyote Creek when a mountain lion leaped on the 14-year-old and tore at his scalp. A woman watching the boys from a sandbar, Isola Kennedy — presumably swaddled in the usual Edwardian corsetry and petticoats — ran to help. The 150-pound mountain lion turned on her, knocked her down and clawed at her face. She fought with her own weapon — an 8-inch hatpin — while the other boys ran for help. A man with a rifle raced back with them and finally managed to get a clean, fatal shot at the lion as it tore at Kennedy. She lost an ear and had a deep laceration on her face and gashes on her left arm. She and the injured boy both seemed to be healing, but six weeks later, the boy died, as did Kennedy three weeks after that, both from what sounded like rabies.

The mysterious big cats fascinate and sometimes frighten us, especially when they become part of urban life. But they are wild and can be dangerous.

The mountain lion’s numbers were uncounted when the Gold Rush landed its several natural catastrophes on California. Within 60 or 70 years, their numbers had tumbled to a near-vanishing point: 600 by one reckoning; 2,000 by another.

In 1925, The Times, with bloodthirsty relish, told the story of a local hunter who “knocked over a whole litter” in one day. Hunting with dogs, he killed a male mountain lion, a female and three cubs, “young devils” that “weighed about 50 pounds each.” The man pledged to go after the mother next. It would be, he vowed, “a good cleaning up.”

The mountain lion had its defenders. Charles Lummis, the swashbuckling turn-of-the-century editor, writer and gallant crusader for Southern California history and culture, wondered why it was a porky-looking grizzly on the original California Republic flag and not the gracile mountain lion, “the most beautiful creature in the New World.”

(The last known California grizzly bear, the official state animal, was likely shot to death in 1922 near Sequoia National Park, where another may have been spotted two years later, the same year it was declared extinct. They too once roamed by the thousands, before humans, in the name of “sport,” trapped and dragged them into arenas to fight bulls and hunted them to extinction.)

Lummis had an unflagging fondness for his own roseate take on the vanished glories of California. The present-day scholar William Alexander McClung wrote about a tendency among Yankee Southern Californians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to summon a “nostalgia for a displaced civilization” — usually displaced by the Yankees themselves — as a yearning “safely insulated from any possibility of reversing the past.” Native American culture, Spanish-Mexican-Californian culture — all safely vanished, sanitized, risk-free.

A guilty nostalgia for what we ourselves have destroyed, along with a modern, science-driven understanding of the complexities of a healthy ecosystem, may explain the turnabout in attitudes toward the mountain lion, the California condor and other imperiled species. It happened too late for the California grizzly, but the rebound in numbers, protection and affection for the mountain lion happened fast.

There could be as few as 4,000 now, and as many as 6,000.

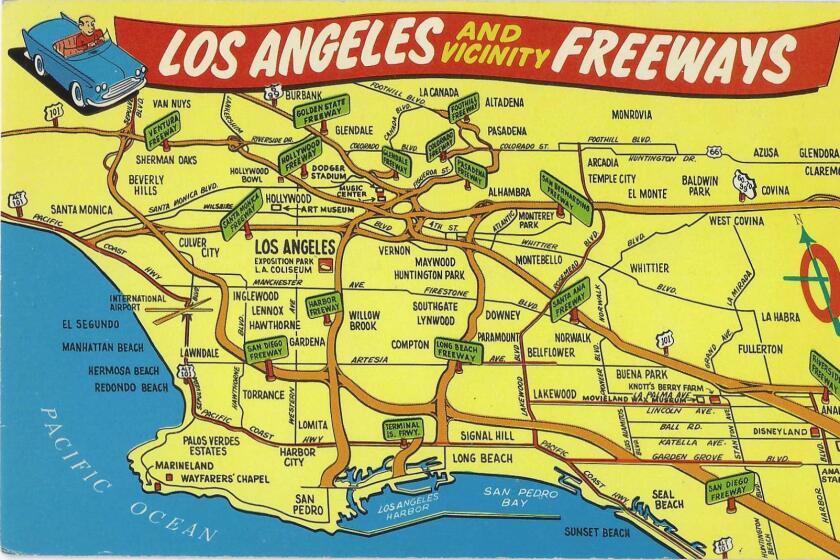

There is no Beverly Hills Freeway. Nor does the 2 connect to the 101. What even is the 90? These are the freeways that didn’t happen as planned.

In 1963, California ended its decades-long bounty, but that seemed to be about saving money, not mountain lions; anyone could kill as many as they liked.

Seven years later — the year of the first Earth Day — attitudes began to shift. The California Fish and Game Commission reclassified mountain lions as a game species and required a hunting license and tag to kill them, and banned killing them with traps and poison. New questions arose: How many are too few? How many are too many? The Legislature took up a hunting moratorium.

In September 1971, a deputy director at the fish and game department declared himself against any moratorium, because the only way to know how many there were was to count the dead ones.

“The study of dead ones adds to our knowledge, which you won’t have when you’re prohibited from harvesting them,” Lawrence Cloyd said. In the same vein, he argued, without offering an example, that most extinct creatures are “those not managed, but which are extended complete protection and nobody pays any attention to them.”

In 1971, Gov. Ronald Reagan signed the four-year hunting moratorium. The state began tagging and tracking mountain lions. The predators could be killed for attacking humans or livestock with a permit good for just 10 days, and only within 10 miles of where the attack happened. (In the three months between Reagan’s signature and the start of the moratorium, 35 mountain lions were hunted and killed.)

Over more than a dozen years, the moratorium was challenged and extended and studied — and it stayed in place.

In the spring of 1986, a mountain lion mauled a 5-year-old girl at a wilderness park in Orange County. That lion was fatally shot after a tranquilizer dart didn’t work. A few months later, a 6-year-old boy was attacked and injured not far from where the girl had been. Someone calculated later that half a dozen mountain lions were living in Orange County’s rustic reaches — a bit of a squeeze when an adult mountain lion needs about 100 square miles of roaming room.

By then it was pretty clear that — as P-22’s fans know — the messaging mattered.

Angelenos can’t help but see themselves in P-22. He’s carved out a life in a crowded city. And though he’s still handsome for his advanced age, he’s terminally single.

The Fish and Game Commission convened a meeting to consider the moratorium in February 1987, a couple of months before the last wild California condor was captured for a breeding program to save the species. Mountain lion lovers put on a made-for-media show.

One couple wore mountain lion costumes and in their paws carried posters saying “NO to trophy hunting!” Actress Tippi Hedren, who had founded a preserve for big cats in Acton, told the commission that “it is almost unbelievable to me to understand the mentality of a person who could allow the lights to be shot out of one of these magnificent creatures.” A Garden Grove man suing to be able to hunt mountain lions described the rigors of the sport: “Few men are tough enough to really be lion hunters.” The audience laughed at him.

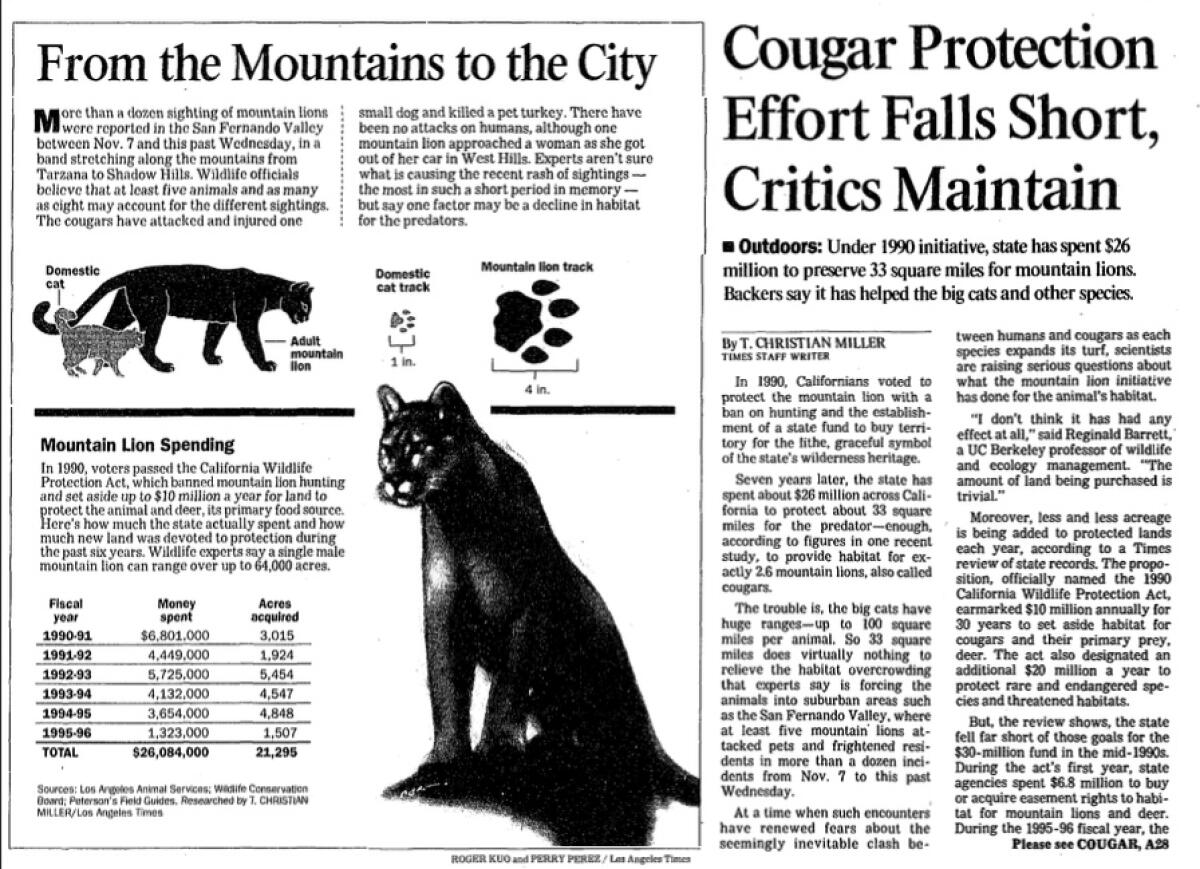

Voters ended up making the decision. In 1990, Proposition 117 created a state conservation fund to buy wildlife habitat and permanently banned the sport hunting of mountain lions, reclassifying them as a protected species. Only fish and game officials could authorize killing them, if they were preying on humans or livestock.

A poll of supporters of Prop. 117, The Times wrote, “found that people reacted more negatively to the lions when told that they regularly kill deer than when informed that lions had mauled a couple of children” in the Orange County incidents. Joe Edmiston, the head of the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, ventured a guess that the rather astonishing reaction was probably because maulings were rare and deer killings a regular event, but even so, “there was a real Bambi constituency out there.”

The fund hasn’t always delivered on its promise, but this month, the 6,000 acres of land bought for open space and wildlife habitat near Castaic was paid for almost completely with money from Prop. 117.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s father led the campaign for Prop. 117, but now Newsom is finding that its restrictions created a paradox. As the Sacramento Bee reported, since Prop 117 passed, more mountain lions — perhaps squeezed by their diminishing range — have been legally killed for attacking livestock than before the measure: about 100 each year. Orange County still reports the most lion-on-human attacks, but they do happen elsewhere in the state. A few have been fatal. In 2004, Mark Jeffrey Reynolds, a cyclist in South Orange County, was attacked and killed by the same mountain lion that mauled a woman later the same day; she survived.

Generals and outlaws, heroes and villains: L.A.’s parks are named for a colorful cast of characters.

One evening in the summer of 1987, a woman named Jean King was ensconced in a bathroom stall in an Orange County Park. A mountain lion poked its whiskered nose beneath the stall door. King hoisted herself to the top of the partition and hung on for dear life until the lion moseyed off.

The moment was preserved by Los Angeles poet Charles Bukowski in “The Lady and the Mountain Lion.” We pick up the tale after the woman screams and help arrives, but the cat is nowhere to be found (stanzas and line breaks omitted): “the story made the newspapers and the television stations. the story that won’t be told is that the lady will never go to the bathroom again without thinking of a mountain lion. a truly beautiful animal.”

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.