Horses, motorcycles and fast cars: Angelenos have long loved racing and racetracks

“Reckless driving on roads and streets must be stopped.”

Pay attention, people, because this is what a world-famous race car driver has to say to Los Angeles.

“A long-suffering public has stood for the reckless driver much longer than it has stood for any like evil, and the worm has turned.”

The champion driver’s name is Barney Oldfield, and he wrote those words in the pages of the Los Angeles Times in 1911 — 111 years ago.

Back then, as now, but at slower speeds and in smaller numbers, street racing was sometimes maiming and killing people, bystanders as well as drivers, even in legitimate events. In 1916, a driver vying for the Vanderbilt Cup in Santa Monica’s immensely popular 8.4-mile street race missed a turn and crashed, killing himself, a movie-company cameraman, a spectator, and a woman running a lemonade stand.

Today the casualties stem largely from illegal, reckless and unsanctioned street racing. Between 2000 and 2017, The Times found, at least 179 people died in apparent street racing accidents in L.A. County.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Maybe you’re inclined to blame the allure of the “Fast & Furious” movies, but filmmakers have been shooting auto race scenes here since Fatty Arbuckle appeared in 1913’s “The Speed King.” The next year, Charlie Chaplin sent his “Little Tramp” into harm’s way in an actual auto race in Venice. The drag-racing scenes in “Grease” and “Rebel Without a Cause” are embedded in civic iconography.

Oldfield himself acted in nine movies over more than 25 years. He is buried among movie folk in a cemetery in Culver City – Culver City, home of one of the earliest of an astonishing number of Los Angeles racetracks, race courses, and dragstrips, 174 of them between 1900 and 2006. By the reckoning of Harold L. Osmer, the author of “Where They Raced: Auto Racing Venues in Los Angeles, 1900-1990,” L.A. was the biggest racing market in the world.

You’d find these raceways on streets and purpose-built tracks in Beverly Hills, Playa del Rey, Saugus and El Sereno, Ontario and Terminal Island, Pasadena and Altadena, and, for a couple of years in the 1930s, on the municipal airfield where LAX eventually arose.

In places, auto racing physically shaped neighborhoods. The documentary “Where They Raced: Speed Demons in the City of Angels” notes that any surviving eucalyptus trees just below and parallel to Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills were planted as a windbreak for the race course above them, and the swirled streets of Culver City and El Sereno follow old racing pathways.

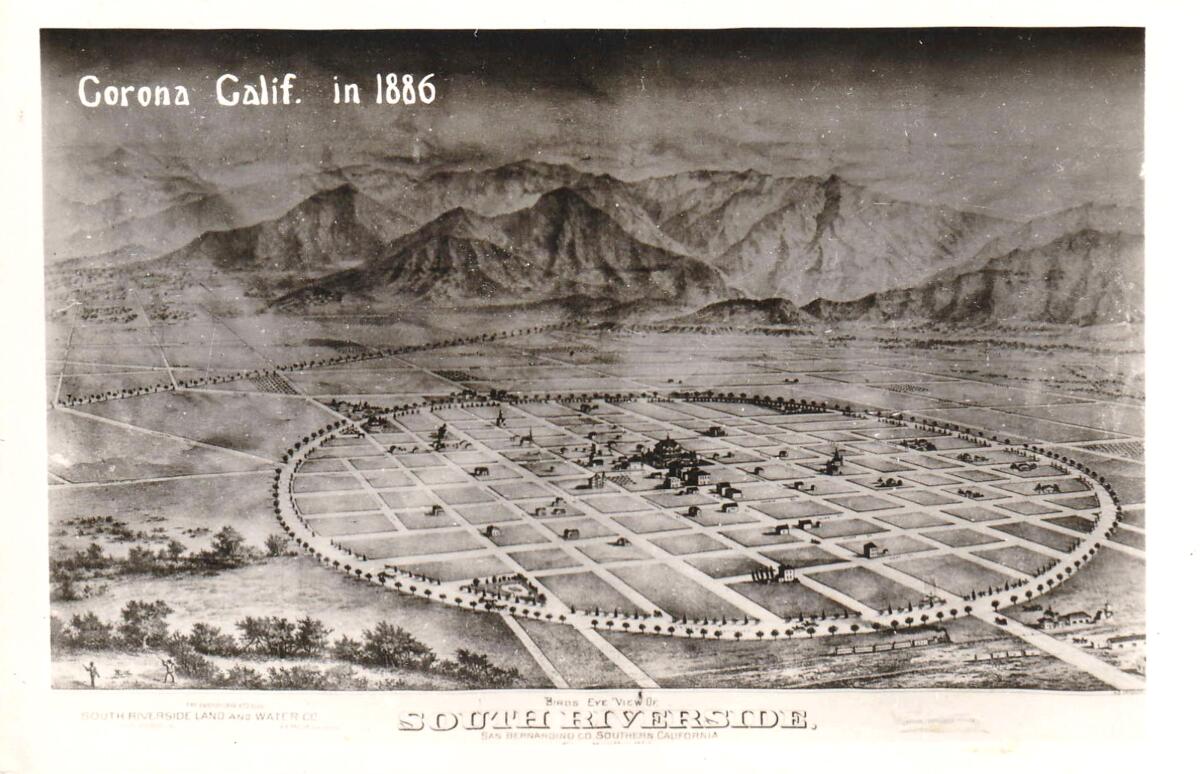

Corona took its “Circle City” nickname from its Grand Boulevard town plan, which was designed by an engineer in 1886 and reimagined as a race course in 1913. That fizzled after the 1916 race killed a driver, a mechanic, and a guard and injured several spectators. Between that gory record and the mess the tourists left behind, Corona had seen enough, and the circle bid adieu to its speed aspirations. The Corona Speedway revived the city’s racing vibe in 1971, but in 1984 it too gave way to the inevitable maw of subdivisions.

Racing did not come to Los Angeles with the automobile. It was already here, in the enticements of broad, flat fields, a clement climate, and the human urge to surge, on horseback or in the driver’s seat.

Racing has been a mania with Californians for, like, ever. As early as 1834, Californios were suing one another over unpaid racing bets. On March 20, 1852, two grandees entered their finest horses in a nine-mile race around a course that began at Seventh and San Pedro in downtown L.A. You will recognize the gentlemen’s names. Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor of California, sent out his California-bred cinnamon-brown horse, Sarco. Ranchero Jose Andres Sepulveda offered up Black Swan, a mare he had brought from Australia.

Everyone in town, and thousands who came to town from as far off as San Diego, laid a bet. Land, gold, flocks — all were on the table. If you didn’t have money, you wagered a pig or a piece of furniture.

Nineteen minutes and 20 seconds after the starting cry ( “Santiago!”), Black Swan and her Black jockey, whose name is lost to history, upended and uplifted hopes and fortunes. Pico had bet, and lost, $25,000, a sum worth something like a million dollars today. He died flat-broke in 1894.

Within a decade of his death, Angelenos were jilting horseflesh contests for horsepower.

Agricultural Park, where you now find Exposition Park just south of USC, was a louche spot for swells and track touts who laid and took bets on horses, camels, and dogs who viciously caught and tore to pieces their terrified rabbit “bait.” Then the 20th century arrived, and the park started offering the prospect of high-octane human catastrophe. At the first “horseless race” there, in November 1903, Oldfield set a world record: a mile in 55 seconds.

Not a month later, the Wright brothers would take to the air in North Carolina for 12 seconds at a pokey 6.8 mph, and soon the derring-do of four wheels would be matched or bested by the daring of two wings. But the ground game was easier to watch and more thrilling. By the tens of thousands, Angelenos crammed themselves into grandstands and alongside oiled-dirt roadways.

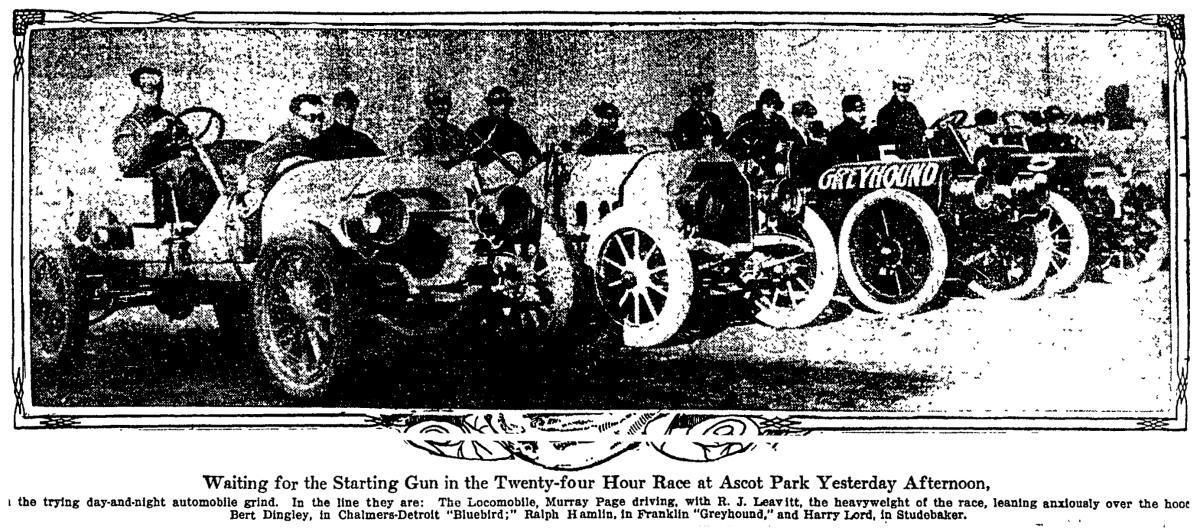

In the early 1900s, the Pasadena-Altadena hill climb drew drivers of cars with marques not seen on our streets for decades now: Franklin, Marmot, Pope-Toledo, Stoddard-Dayton. Theirs were feats of endurance as well as speed, huffing up the foothills past spectators who were well-behaved — “good-natured and free of advice,” as The Times reported, evidently meaning not hollering or jeering at the drivers. The race’s “Perpetual Challenge” trophy, if you believe a 1910 motorcycle, boat and automobile trade directory, was “the most coveted trophy in California.” Like Kilroy, like Zelig, the ubiquitous Barney Oldfield drove here, too.

He also raced at the first of several local Ascot Parks, this one at Slauson and Central Avenue, which was then outside the L.A. city limits and so beyond the city’s limits on vices like liquor.

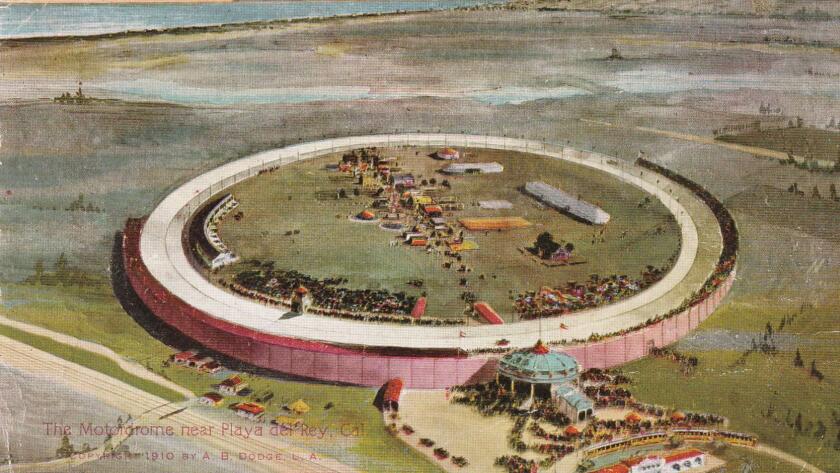

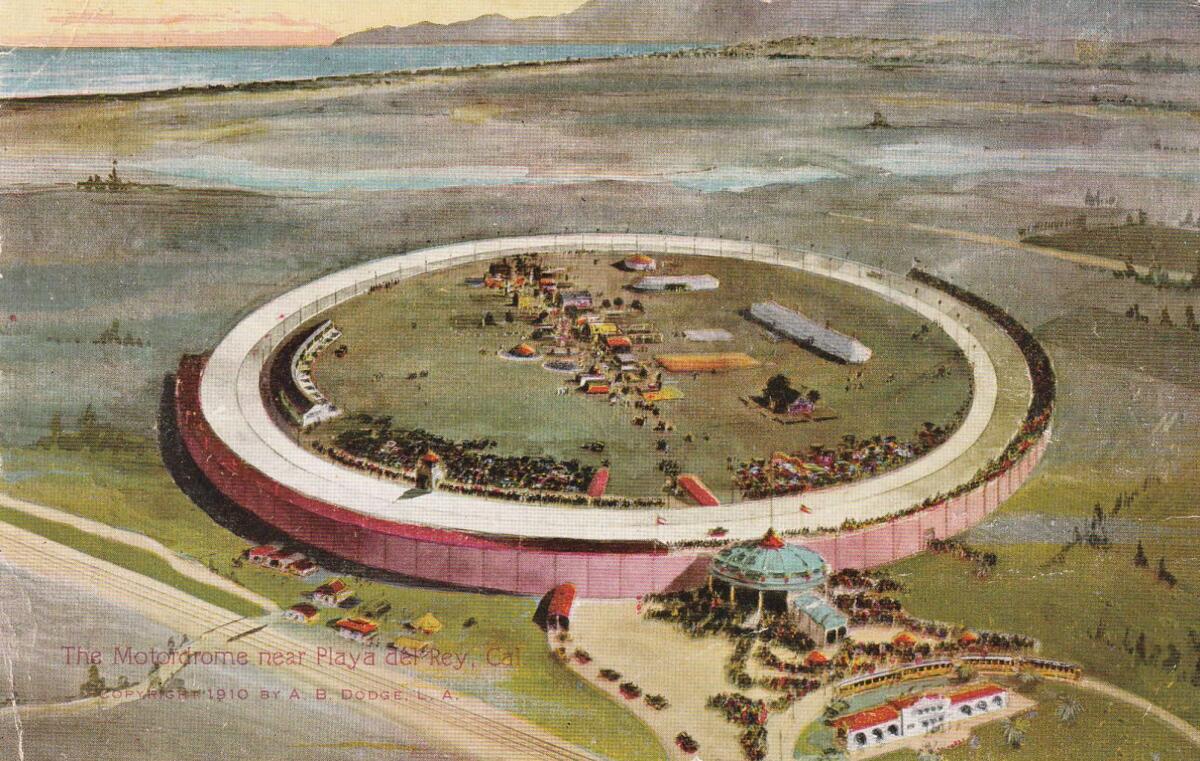

The first of the “toothpick ovals,” wooden racetracks built from two-by-fours, opened in 1910 in Playa del Rey, at the ocean’s edge. It was built in barely two weeks, from 300 miles of two-by-fours and 30 tons of 16-penny nails, which over time began to work their way loose under the racers’ tires. Streetcar service brought tens of thousands right to the gates of the one-mile “Piepan,” where Oldfield again set records. The wood planking was soon soaked with racing oil, so no one should have been surprised that, three years after the track opened, some vagrants lounging and smoking beneath the oval, out of the August sun, set fire to the thing and turned it into an ashy ruin.

The Beverly Hills speedway — also called, less grandly, the Los Angeles speedway — was the next “toothpick” track, opened in 1920 on 275 acres of land purchased for $1,000 an acre. Construction had to wait until the seller brought in his bean crop. Silent film stars had a special enclosed VIP section in the grandstands, overlooking a course that took a turn where the Beverly Wilshire Hotel now rises.

It opened on February 28, 1920, to a gate of 50,000 people. On Thanksgiving Day that year, two drivers and a mechanic riding shotgun were killed in a crash.

It wasn’t long before development became a more enticing option than beans or speed, and in 1924, the land sold for a reported tenfold-per-acre price. Within months thereafter, the Culver City “toothpick” speedway was up and running, until it, too, was killed off by subdivision dreams, in 1927.

Their names are mysterious — Mazdaznan, Thelema and Synanon, to name a few — but their playbooks have been remarkably similar. Here’s a look at crackpot credos that flourished and foundered in L.A.

Once L.A.’s original Ascot raceway shut down after World War I, a second one sprang up in El Sereno, just beyond Lincoln Park. A Glendale American Legion post took it over for a number of years, which is why it was called Legion Ascot.

Legion Ascot is where the race helmet first appeared, on the noggin of a driver named Wilbur Shaw. He was mocked as a chicken until the “brain bucket” saved him in a headlong encounter with a guard rail, and pretty soon all the guys were wearing them. Still, Legion Ascot’s reputation as the deadliest race course around — two dozen men killed in a dozen years — probably helped to do it in. People may like to go to the races anticipating crashes, but the real thing may make them sick.

A janitor named Linden Emerson confessed that he set fire to the grandstand four months after the course closed. He’d seen two men die out there, and “I thought maybe they might reopen it and kill some more of my friends. So I decided to burn the grandstand down.”

With its air of English grandeur, “Ascot” was too good a name to abandon, and another Ascot track opened around South Gate for a few years before World War II. Still another Ascot, New Ascot Stadium, revved its engines in 1958 on an old speedway. The 36 acres had been a dump at Vermont and 183rd on the old “city strip” before it opened for motorcycle races in 1957. The next year, promoter and impresario J.C. Agajanian took it over, and his family ran it until its last lease expired in 1990. It may be a trick of memory, but I could swear I remember those hyperventilating reverb-drenched radio ads “ASCOT Ascot Ascot PARK Park Park!”

Over time, building kept besting racing. Construction kept shoving racetracks and race courses farther and farther into the hinterlands. Long Beach’s grand prix street race, which dropped its first green flag in 1975, is one of the few survivors from the massive events like the Santa Monica and Venice and Pasadena races.

The dragstrips that flourished right after World War II also got elbowed out of the way, when race venues in even once-faraway places like San Fernando, Baldwin Park, Palmdale, and Wilmington turned out to be taking up land that someone wanted for subdivisions and industry.

One of them was a dragstrip at Terminal Island called Brotherhood Raceway Park, which finally closed in 1995, but not before Times Publisher Otis Chandler moved ink and muscle to preserve it.

Now, Chandler was a skilled race car driver who’d delivered some hair-raising performances at places like Watkins Glen and Laguna Seca. I was there at his memorial in a Pasadena church in 2006 when, unexpectedly, a big Black man in a black leather racing vest walked up the center aisle. Stitched onto the back of the vest were the words “PRESIDENT” and “STREET RACERS INTERNATIONAL.”

His name was Big Willie Robinson, and he rocked that nave with his tribute to “Big O.”

“God pinned a gold star on his chest. I’m gonna tell you why,” said Big Willie. Otis had helped to save, for L.A.’s Black and Brown drag-racers, the dragstrip that Big Willie had helped to put together after the Watts riots and keep it together after the Rodney King one.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Not long after Richard Riordan was elected mayor in 1993, Chandler wrote him a letter, asking the city to preserve the raceway: ”For the last several years he has been struggling to run a car drag program at the Terminal Island facility … where the youth can spend their energies racing each other in cars, rather than using knives and guns.’’ The track survived, briefly, until the city took the land back for a coal-handling plant in 1995. Times writer Daniel Miller has recently put together a podcast about Big Willie’s life.

Every last drop of high-performance oil has not yet been squeezed out yonder. Next February, just before the Daytona 500 in Florida, and 120 years after Barney Oldfield beat the rest of the fleet a few dozen yards away, NASCAR will bring back to the Los Angeles Coliseum a season-opening, quarter-mile stock-car race. I mean, “NASCAR CAR CAR! At the COLISEUM Seum Seum! Be THERE There There!”

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.