One roamed for hours through an oak preserve asking God to speak to her through the silence.

Another spent her days in meditation, using each exhale to send relief to her son, who had, by then, slipped out of consciousness. Not long before, a third woman had awakened in the middle of the night to what became a terrifying, recurring dream about descending into hell.

Each woman — members of three generations — went through a spiritual journey that had been sparked, sped up or heightened by the pandemic.

The last two years have transformed the stability of our families, our jobs and our collective understanding of science and sacrifice. But, for many of us, COVID-19’s reach also rewired something more elemental: our faith.

A Pew survey conducted early in the pandemic, found that nearly 3 in 10 Americans said their religious faith had become stronger since the coronavirus outbreak.

For others, this time has fundamentally changed their place within their religious traditions or led them to question long-held beliefs altogether — processes of introspection and transfiguration that can be, at once, painful and deeply fruitful.

“Suffering,” one of the women said, “sometimes forces us to look at the gold mine we’re sitting on.”

The pastor

During the first fall of the pandemic, as she was clawing her way through a blinding depression, Esther Loewen told her wife, Paige, something she’d long feared would end both her marriage and her career as a Seventh-Day Adventist pastor.

“I’m afraid I might be trans.”

They sobbed and hugged and Paige made a promise: “I’m not going anywhere.”

A few months later, Loewen emailed her mother to explain that the person she’d long thought of as her eldest son was, in fact, her daughter. Her new name was Esther Elizabeth.

The revelation was hard for her mother. But Loewen, now 40, said her mother has come far in a short time, switching from using her deadname to “Elle,” a short version of her new middle name. Next, Loewen and her wife told their two sons, then 9 and 6, who quickly settled on a nickname of their own: Mapa.

In many ways, she said, the pandemic shutdowns provided the framework she needed to come out. For the first time ever, she was isolated from the social pressures and fears that had prevented her from transitioning. From her home in Redlands, she connected with other transgender Christians in Zoom support groups, which provided some relief from the bone-deep exhaustion that had come with pastoring a congregation with split views on masking and other COVID-19 safety measures.

Loewen knew her denomination had a longstanding record of barring LGBTQ people from church leadership, but because she was preaching remotely at the time, she’d felt comfortable to begin growing out her hair, keeping her beard closely cropped and painting her toenails. But she hadn’t yet decided whether to take hormones.

Before she took that step, she wanted to hear a blessing from God — and it finally came in January 2021 while at a retreat for church leaders at an oak preserve in Yucaipa.

During several hours of solitude, she prayed — “What do you want to tell me today?” — then she rounded a corner and saw hundreds of monarch butterflies. Like many trans people, she sees the caterpillar-to-butterfly transition as a beautiful analogy and, in that moment, she burst into laughter and then tears.

“It shifted from being like, ‘Can I do this?’” she said, “to ‘I have to do this in order to be faithful to God.’”

It felt just as clear as the calling, years earlier, to a life of ministry — a vocation born out of the faith she’d clung to as a teenager after surviving a house fire that killed her younger brother. It was a job she loved dearly, but also one that often made her think about privacy and secrecy.

“Don’t put your trash in the can out front,” an older pastor once had advised her, explaining that church members had interrogated him after finding an empty carton of ice cream, which would be off limits to the strictest Adventists, who are vegan.

She wouldn’t lie outright, but Loewen decided that church members didn’t need to know everything about her private life, including the time she wrote a letter to a friend, who is a lesbian, telling her she was loved by God exactly as she was and that the church was wrong on this issue.

She never dared say such a thing publicly, a reality that made her feel complicit then and guilty now. She sometimes thinks about times she sat around boardroom tables, listening to church leaders say hurtful, exclusionary things and didn’t speak up. And yet, she tries to welcome God’s grace, understanding that deep down, even then, she knew she was trans.

Last summer, as her depression deepened, she sat down with fellow church leaders and told them she was trans. She desperately hoped she could keep her job, she told them, suggesting they move her to a church in a more liberal area. The leaders handled the situation about as generously as they could have given church rules, she said, but it was clear she had to resign.

It was one of the heaviest losses of her life, she said, but still she feels closer to God than ever.

On a recent afternoon, Loewen, who is studying to become a therapist, picked up her younger son from school and took him to a park. A little girl on the swing next to him looked over at Loewen and then turned to her grandmother.

“What’s wrong with that lady?”

Her son turned confidently toward the girl.

“She’s transgender and she’s my Mapa.”

The ‘exvangelical’

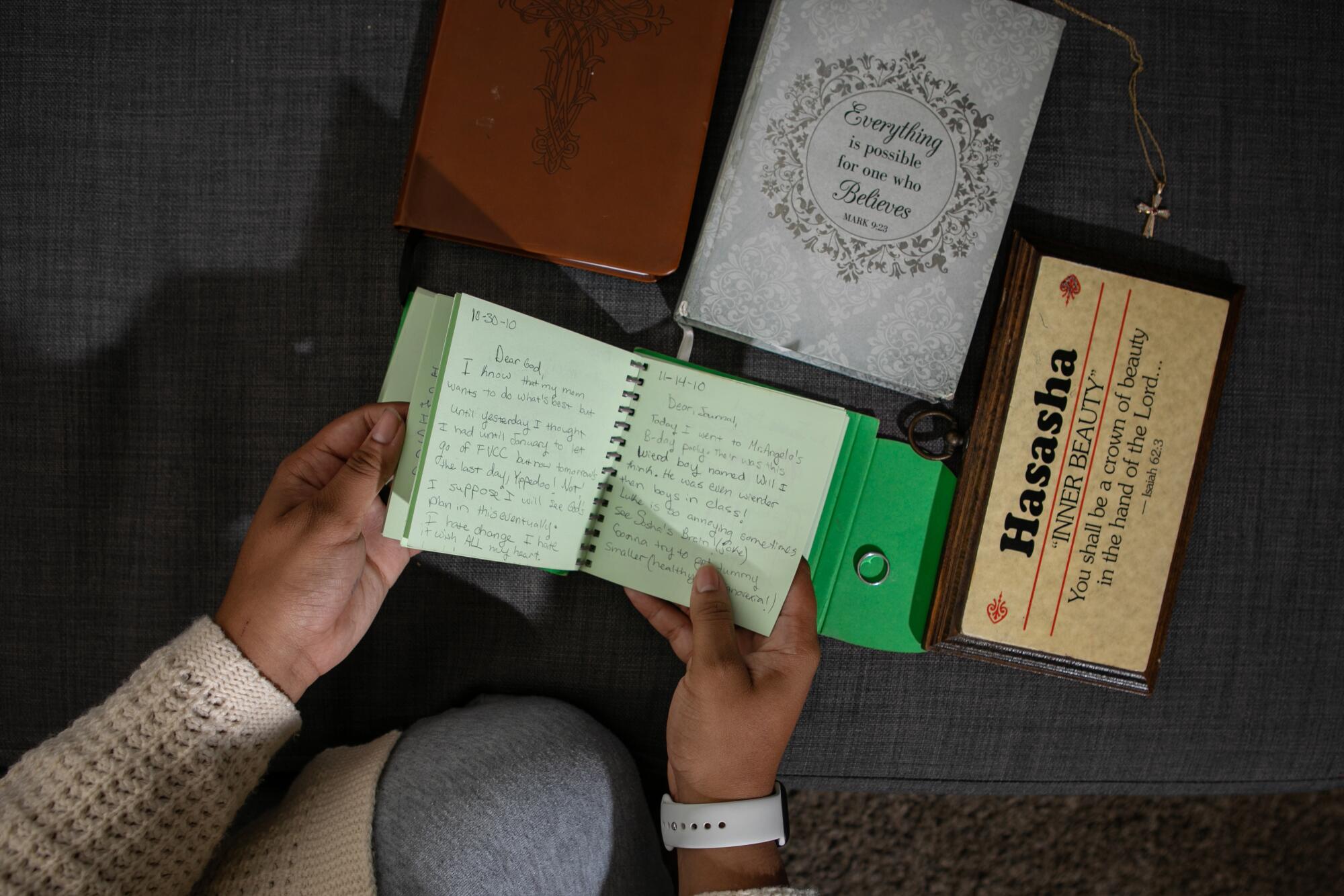

One day, when she was 9, Hasasha Hasulube-George recalls sitting on her bed sobbing.

“I’m such a bad girl,” she’d written in her journal.

She can’t remember what she got in trouble for that day — forgetting to clean her room, perhaps. But she vividly recalls her mother assuring her that if she asked Jesus into her heart, he would help her. So she prayed and relief washed over her.

By 12, she had pored through the Bible and soon after she read “I Kissed Dating Goodbye,” a purity culture classic during the early aughts. She proudly wore a silver promise ring inscribed with “True Love Waits” and woke up early on schooldays to pray.

And yet, a countervailing force buffeted her spiritual life: a dawning awareness that her family’s racial identity — her father is Black, her mother white — set them apart from the rest of their worship community in suburban Chicago.

Hasulube-George, now 24, recalls a church picnic where members of their congregation repeatedly told her brothers to only take what they could eat and not go back for seconds. They said nothing to the other teenagers in line, who were white.

So often, she said, conversations about race in white, evangelical circles — when they happened at all — quickly pivoted to the same line: “One day we’ll all go to Heaven and color will not matter.”

Still, she found deep community among fellow believers. When she thought about her few friends who weren’t Christians, it filled her with dread. What if she never tried to convert them and they died? Going to hell, she’d learned, was like getting stuck in a dark cave, separated from God for eternity and surrounded by deafening silence.

It was that same image that had haunted her dreams during the first summer of the pandemic.

By then, her then-fiancé, Hunter George, whom she’d met in college in Indiana, had been laid off from his job at a nonprofit and the cleaning job she had lined up after graduation fell through. The couple moved into Hunter’s parents’ basement in Rochester, N.Y.

She could almost always hear Fox News on the TV upstairs, with rotating headlines about the impending presidential election and mask mandates, or talking heads framing the social justice protests after the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd only in the context of property damage. Family members sent her and Hunter, who is white, emails suggesting that Black Lives Matter was against God and Trump was ordained by the Lord.

That’s when the nightmares started.

Like Arbery, who was shot to death by a white man while out for a jog, in her dreams Hasulube-George would be running when someone, often a neighbor, would shoot her dead. She’d then descend into the quiet-cave version of hell and be trapped there until she woke up in a panic.

She told Hunter she needed to get rid of her Bible. She couldn’t stop thinking about verses she’d underlined years earlier that she now felt condemned by. He understood.

In the weeks that followed, she remembers sitting on Zoom calls for Christian premarital counseling with a longtime mentor and thinking it felt like a farce. She and Hunter were actively trying to get pregnant, but she knew she couldn’t be upfront about that. She was trying to hold onto the final shreds of her faith until her wedding day in September 2020.

“My farewell party to my old life,” she came to think of it.

Soon after, she started having conversations, sometimes painful ones, with friends and family about her decision. A verse she’d once memorized — “Children, obey your parents in the Lord” — now felt like a dagger.

Her mother initially responded with deep fear, she said, but time has softened the situation.

Since moving to North Hollywood last summer, the couple has continued to deconstruct their faiths. Hunter has vowed off organized religion and she has begun researching African spiritualism, specifically traditions from her father’s native Uganda.

She misses the structure her faith offered — for years, she relied on prayer as a tool to regulate her anxiety — but she has, again, found community in an online book club for fellow “exvangelicals.”

While she thinks she probably would have left her faith eventually, she said that watching the trifecta of pandemic-era scenarios play out in 2020 — the “don’t-wear-a-mask-God-will-protect-you” comments, the evangelical fervor for Trump and the response she saw from many Christians during the social justice protests — both crystalized and sped up her decision.

“That pushed me to decide, ‘I’m done.’”

The religious studies professor

Fran Grace clearly remembers the origin point of a twisting spiritual pathway that has helped guide her through the pandemic.

It was four decades ago and her high school English teacher was reading aloud from “The Scarlet Letter.” Only half-listening to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s tale of sin and repentance, she saw a pillar of light slice down, as if piercing through the ceiling, and felt as if she melted into the incandescence.

She interpreted it, at first, as a sign that something infinitely loving existed inside of her. But the revelation calcified into fear after her mother took her to see the pastor of a small Protestant church in her Florida town.

“You’ve got the devil inside you, young lady,” he proclaimed.

Now, further along in a journey that has included joining and leaving a fundamentalist Christian church, divorcing her husband, falling in love with a woman for the first time, drinking herself to near-death, finding sobriety and traveling to study world religions, Grace — a professor of religious studies at the University of Redlands — looks back fondly on that day in high school as the start of a lifelong quest that has buoyed her during the hardest times in her life.

At the tail end of last summer, Peter Boyko — her partner Diane Eller-Boyko’s son, whom she’d come to think of as her own — was hospitalized with COVID-19. Before long, the 29-year-old father of three was struggling to breathe.

Restricted from frequent visits, Grace and Eller-Boyko, who both follow the Sufi path, dug into spiritual tools they’d long relied on: meditation, dream work and paying attention to small signs.

Soon after Peter died, a letter addressed to him showed up at the couple’s home. The note from a children’s charity included a line about accepting people just as they are — a trait that was exceptionally true of Peter. It was a hint, Grace believed, from the inner world.

She felt more tuned into the kindness of others, often reflecting on the proverb about how suffering often points us to the goldmine beneath us. And as the pandemic lingers, she has tried to help others find that spiritual gold.

One Wednesday in December, Grace, 57, sat cross-legged in front of a camera inside the Meditation Room, an airy, carpeted space adjacent to her office at the University of Redlands.

For years, Grace has led free, weekly meditation sessions for students and other members of the community and although she’d returned in person by December, most of the attendees were still joining virtually. One by one, their smiling faces popped up in small squares as they joined from San Diego, Tucson, Canada.

Grace asked everyone to close their eyes.

“Relax, relax, relax,” she guided them.

Sense your right leg, she said, and then your left. Let your belly fall open and relax the muscles in your throat. Open your heart and offer yourself in service to others. Think of a stranger and send them love.

Later, they went around the virtual circle, sharing about their weeks and whom they had selected as their “stranger” while meditating.

A 91-year-old from San Diego had thought of the volunteer who drove her to a dentist appointment a few days earlier. An Iowa State University student pictured the cafeteria employee who handed her ice cream on her birthday. A Presbyterian minister recalled a man on Death Row at San Quentin who had started as a pen pal and became a close friend; during the meditation, the minister said, she had prayed for the women he killed.

“Wow,” Grace whispered.

When it was his turn to share, a man from British Columbia, who was sitting cross-legged on his floor, told the group that his father had died a week earlier. He began to cry, resting his forehead on the ground.

Grace closed her eyes. As she inhaled, she focused on breathing in his suffering. With her exhale, she sent out hope.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.