Death Valley National Park — It was only a matter of hours before the hallucinations took hold.

“I am starting to crack,” Cameron Hummels texted on a February morning after hiking more than 113 miles on foot in one of the most desolate, extreme environments on the face of the planet: Death Valley.

After five hours of restless sleep, Hummels, 43, awoke that day to lashing winds and harsh sun on his face. A feeling of complete isolation seized him as he gazed out across Badwater Basin, a barren salt flat that holds the title of lowest point in the Western Hemisphere — in the hottest region on Earth.

His goal was to traverse the entirety of Death Valley National Park on foot in four days — cutting the previous record nearly in half. To do that, he would need to cover the next 56 miles and change without sleeping. Already he’d endured a furious sand storm, dodged vents spewing toxic gas, chugged water laced with arsenic.

It was the final push — 24 hours awake and in motion.

Soon after he set out that Monday, nausea set in. Then nosebleeds and diarrhea.

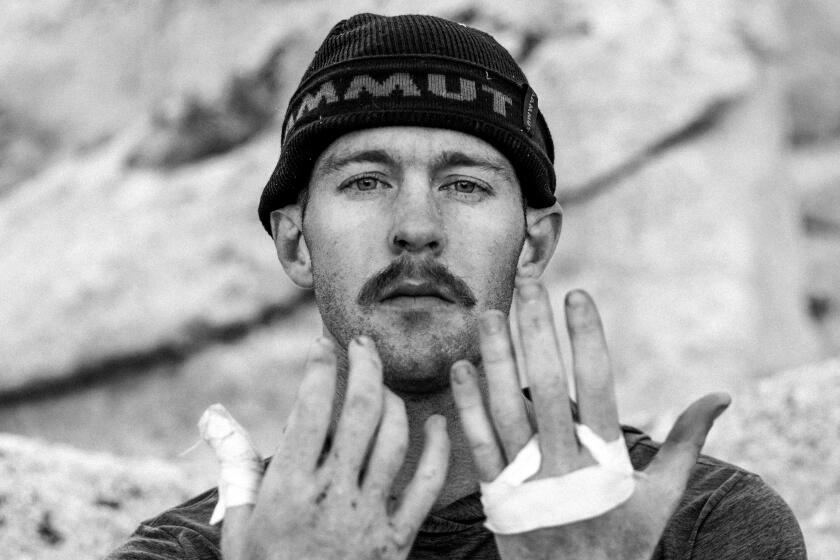

The wiry, sandy-haired astrophysicist is part of a growing subculture of endurance obsessives — men and women who have set their sights on completing outdoor running and hiking feats and breaking arcane records in the process. They compete in the insular world of fastest known times, or FKTs, jockeying to capture records that come with minimal glory but often plenty of pain. With so many traditional races canceled during the COVID-19 pandemic, the FKT movement surged in popularity.

Hummels keyed in to one of the movement’s more obscure routes, in which the “hiker has to feel/act as he/she is the only one on the planet,” according to the creator’s rules. It’s perhaps not the tallest order in the lonely expanse that is Death Valley, but Hummels took the extreme measure one step further: He brought only 2 liters of water for the roughly 170-mile trek.

“Not going to give up,” continued the message he texted from a satellite device.

Actually, though, he wasn’t sure.

“Am going crazy with sleep dep and fatigue,” he wrote.

It wasn’t even 8 a.m. There were still more than 24 hours to go.

::

Hummels is an ultrarunner and through-hiker, an athlete who walks long-distance trails such as the Pacific Crest (2,653 miles) from beginning to end. He started thinking about crossing Death Valley before he knew he could earn a record for it.

He was fascinated by the valley’s extremes, its promise of rare solitude in a world where humans have reached every far-flung corner. The park’s inky night skies are famous for stargazing — a particular draw for someone whose livelihood is intertwined with space. On Strava, a social platform for tracking exercise, Hummels’ profile name is Luke Skywalker. He applied to be an astronaut. Though Death Valley isn’t the final frontier, it’s nearly as lonely.

And like many drawn to extreme sports, Hummels courts suffering.

“It makes the highs higher to have the lows lower,” he said cheerfully in a recent interview.

About three years ago, while reading “Hiking Death Valley” by Michel Digonnet, a comprehensive guide to the barren landscape, Hummels came across a description of a route that stretched from the north end of the park to its southern tip. It was laid out as something that could be tackled over weeks, not days.

When Hummels began to look into hiking the route, he discovered that two intrepid Europeans had already made the crossing and recorded their times at fastestknowntime.com. The website is the closest thing to a record book for endurance junkies.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Louis-Philippe Loncke, a self-described Belgian explorer, logged the first crossing in 2015 at just under eight days. In 2019, Frenchman Roland Banas broke the record when he clocked in at a little under seven days. Both men completed the traverse alone, off-trail and unsupported.

Hummels longed to join the leaderboard. Though he frequently described the project as “silly,” it jibes with the ethos of FKT culture. Peter Bakwin, who co-founded the Fastest Known Time site, told the New York Times, “The only authority I have is that I started this stupid little website.”

As route pioneer, Loncke wrote the rules. To qualify for the unsupported FKT, no one can help you. Civilization is to be avoided. National park rules must be observed. All food and water have to be carried from the get-go. Nothing can be stashed along the way. But natural resources are fair game.

In Death Valley, the driest place in North America, there’s not much water for the lapping. Loncke and Banas lugged their entire supply on their backs. Between food, water and gear, Banas set out with 90 pounds, he said in his trip report. Loncke, in his own report, said he fell several times under the weight of his heavy pack during his first day.

Hummels felt he could easily shave days off the journey if he traveled lighter.

All he had to do was find water along the way that wouldn’t kill him.

::

The park is nominally bone-dry, with just tiny seeps and springs fed by snowmelt or underground aquifers. But they’re few and far between. Many are seasonal. Others are dangerous to drink from because of high levels of arsenic, uranium or salt.

To track down the water sources, the Caltech computational astrophysicist launched into a research rabbit hole. First he scoured the internet for clues, but he found limited resources. Why would people identify potentially hazardous water, when they could just buy it at the gas station or fill up at a spigot? Even the park hydrologist didn’t have the information Hummels needed for his quest.

So Hummels looked further back in time — to more than 100 years ago, when a mining boom drew visitors to the region. He turned up a U.S. Geological Survey report from 1909 called “Some Desert Watering Places in Southeastern California and Southwestern Nevada.” Then he pulled up satellite images and identified patches of vegetation, potential signs of H2O.

Whenever Hummels visited the park, he’d hike to one of the spots. There might be a centimeter-deep puddle. Often, there was nothing at all.

He collected water samples and sent them to be tested for chemicals, bacteria and other unseen menaces.

Jackson Parell and Sammy Potter hatched an ambitious plan during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic: to hike three of the nation’s most arduous trails — the Appalachian, Pacific Crest and Continental Divide — in a single year.

None of the water was pristine, to say the least. Some had high levels of salt or uranium. One had five times the federal limit of arsenic, “which is not great,” he said.

Still, he reasoned, filtering and drinking a limited amount over a short period of time would be OK.

Just to make sure, he decided to guzzle some in the safety of his Pasadena home.

“I’d rather vomit or faint within my home instead of being in, like, 100-degree weather on the valley floor, where if I faint, I’m dead,” Hummels said in late February 2021.

About a week later, on March 5, Hummels announced online his intention to traverse the park two days later. (It’s necessary to give notice and document the trip to capture the FKT.)

But when March 7 rolled around, Hummels “felt like complete garbage,” he wrote in the comments section for the route on the Fastest Known Time site.

First he postponed the trip by a day, then a week. But he still didn’t feel well.

He was at the start of a long, mysterious illness.

Months passed, marked by bouts of nausea, headaches and fatigue.

A clear answer never came. Tests, including several for COVID-19, came back negative. Visits to specialists were inconclusive.

The culprit, Hummels believes, was a virus in the water he had collected.

But instead of giving up, he decided to double down on treating the water. In addition to filtering it, he’d add chlorine dioxide drops to knock out all the baddies.

Ultimately, it took a year for Hummels to find the nexus of decent weather and good health to attempt the journey.

Last month, on Valentine’s Day, he finally set out.

After a spinal cord injury left him paralyzed, Jack Ryan Greener centered his life on a quest to hike Mt. Whitney. When the time came to try, the quest proved perilous.

::

Hummels felt exuberant as he began his journey at 7,000 feet, in the snowy Sylvania Mountains.

It was fun — and fast — to descend Last Chance Wash into Death Valley proper.

It didn’t matter that he’d barely slept the night before or that the bushy Joshua trees and pinyon pines were shredding his skin. His pack was a relatively light 25.4 pounds, and he carried just 2 liters of water to tide him over until he reached a small seep at Mile 17.

An epic sunset enveloped him as he strode past the wide maw of the Ubehebe Crater.

He’d managed nearly 37 miles. It was a good day and would prove the easiest of Hummels’ expedition. But the water he collected along the first leg of the journey was high in arsenic. Nausea was already kicking it.

By the morning of Feb. 15, his good spirits had flattened to just “OK.”

At sunrise, Hummels rose and packed up camp — a humble bivy and a sleeping quilt. It was brisk, below 40 degrees. He drained blisters, taped trouble spots and gulped down 1,200 calories of oatmeal and olive oil.

Before heading out, he filtered 7 liters of water. Two he chugged on the spot; the rest would accompany him for the next 40 miles.

As a forecast windstorm arrived in late morning, fierce gusts of up to 50 mph pushed him around and kicked up sand and dust. The debris was vaulted into the air and formed a haboob — a towering wall of sand. To keep the particulate matter out of his lungs, he strapped on an N95 mask.

After crossing drainages and salt-sand features, Hummels dropped into a canyon in the Kit Fox Hills, which shielded him from the brunt of the wind.

Eventually he landed at Keane Wonder Springs, his destination for the night. He had completed just over 40 miles. A nearby hydrogen sulfide vent was spewing toxic gas. So he filled up on water as quickly as he could and scampered up the hillside — beyond an old miner’s cabin.

The gas is heavier than air, and Hummels reasoned that it would be safer to camp above its source. Still, he had inhaled enough of it to make his sinuses burn. The following day, his nose would bleed and bleed.

He made camp at about 12:30 a.m., and he still needed to eat, drink and lance blisters. At 2 a.m. he bedded down, the wind still howling.

Hummels awoke on Feb. 16 after just four hours of uneasy sleep. This was the leg of the journey he’d been dreading the most because of the rough terrain of the salt flats ahead.

Both men who had completed the route before him similarly wrestled with physical and psychological distress on the third day.

That day, Banas wrote, “was the beginning of a crescendo in pain and difficulties.” Loncke summed it up: “Whatever the expedition, the third day is always difficult.”

After hiking for about six miles, Hummels reached Highway 190, a main thoroughfare in the park. It marked the halfway point of his journey. Cars whizzed by. It might have been a welcome sight to another weary traveler, but he was on a different planet now. He scurried past, eager to get away from civilization.

The terrain on the flats alternated between salt marsh, where his feet sank with each step, and salt stalagmites, which rose between 6 inches and 2 feet. He dubbed the stalagmites “fairy castles” as he strode past them.

Under the midday sun, the temperature soared past 100 degrees. He passed by mysterious tilled rows where miners had harvested borax more than 100 years ago.

Winds kicked up again in the late afternoon. But there was nowhere to hide on the flats, and he had so many miles to go.

As the sun set, Hummels began trekking over salt polygons rising from the earth. The flats are known for these strange terrestrial patterns. But navigating the crystalline ridges in the dark proved treacherous.

Around midnight he reached Eagle Borax Spring, where he replenished his water. Utterly exhausted, he drifted off to sleep around 2:30 a.m. at the foot of snowcapped Telescope Peak.

When he awoke five hours later, he felt awful.

It was Feb. 17, his final day. The longest stretch by far lay ahead — a more than 24-hour push to the finish.

His doubts reached a fever pitch. That’s when he shot off the crestfallen messages.

“You don’t have to come,” he wrote to this reporter. “But if you do come, I will give you 100 dollars to drive me back to my car in the park.” Nine miles separated vehicle and trip’s end. His plan had been to walk. Suddenly, it didn’t seem like such a good idea anymore.

“I guess this is what happens,” he wrote, “when you press up against the boundaries of what you can accomplish.”

Hummels’ girlfriend, Katherine de Kleer, was concerned enough to contemplate traveling to the area. But there was a snag: She had left her car in the park so he could drive it back. She remained at home, worrying.

Unsure if he would reach his goal, Hummels pressed on. Through surreal terrain he called “soft marshmallow soil” and “frosted flakes.” Along the banks of the Amargosa River, sometimes sinking into its muddy grasp.

Between sunset and moonrise, he stopped to eat and rest his legs and feet, which were now in near-constant agony. He checked his electronics. The charges were perilously low. Panic set in.

If the GPS device he was using to track the traverse died before he reached the finish, he’d have no proof of his accomplishment. It appeared to have just enough juice to last through 11 a.m. He’d have to hurry.

With 30 miles behind him, but a marathon’s worth of trail still to go, he began to hallucinate. To hear, see and even smell things that weren’t there.

A woman called his name. An irritating leaf blower whirred in the empty expanse. Animated shadows tickled his peripheral vision. A ghostly coyote ran beside him. The imaginary scent of the drops he used to treat his water choked him.

Every few miles, he lay on his back and propped up his feet to alleviate the searing pain. Time blurred and contorted.

It was only when the sun came up on Feb. 18 that he felt he might actually make it.

By 7:15 a.m., he reached what looks like a mirage in the arid expanse. It was Saratoga Springs — large, glittering pools teeming with pupfish.

The finish line was nine miles away. He could hobble there by 11 a.m.

After about a mile, he tried jogging a few steps. To his surprise, his feet obeyed.

Hummels sprinted to the finish, emerging like a dark-blue bolt from the brown dust.

It was 9:25 a.m. His goal had been to complete the trek in 96 hours.

He finished with six minutes to spare.

Sitting on a thin pad, he whipped a Luke Skywalker Lego figurine — his alter ego — from his pocket. He grinned.

Trucks hurtled by on nearby Death Valley Road. A man pulled over and set up a camping stove for no apparent reason. Dune buggies rolled past, kicking up dust as they disappeared on the dirt roads.

“It’s silly,” he said. “It’s totally silly.”

But he’d made it.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.