How to remember the Japanese incarceration, 80 years later

Akemi Leung knew her grandfather had been incarcerated at the Poston camp in Arizona during World War II.

But he never spoke much about it.

For the record:

11:18 a.m. Feb. 22, 2022An earlier version of this article reported that more than 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry were forced into concentration camps. The number includes Japanese Americans and citizens of Japan residing in the U.S.

3:21 p.m. Feb. 19, 2022An earlier version of this article reported that Akemi Leung’s grandfather was incarcerated at Heart Mountain. He was at the Poston camp in Arizona.

Only when she read and watched a video of his testimony at a congressional commission hearing did she learn more about what he suffered as one of more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry forced to leave their homes and live in concentration camps.

“I just knew him to be a quiet person who liked to observe more than talk,” Leung said. “Seeing the testimony helped illustrate how he was a leader.”

The hearing happened decades ago. By the time she watched the tape in 2017, her grandfather, Hiroshi Kamei, had already died.

With the 80th anniversary of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which authorized the incarceration of Japanese Americans as a supposed threat to national security, the ranks of survivors are thinning.

Many went to their graves without sharing their experiences with their families.

As Japanese Americans mourn the passing of a generation, they are trying to preserve the memory of what their elders went through, sometimes using modern technology like podcasts and virtual reality.

The effort is especially important at a time of rising hate crimes against Asian Americans and pushback in some places against educating students about racial injustices, some say.

“Every generation has to rediscover the story, understand it and tell it in their own way,” said Tom Ikeda, the founding executive director of Densho, a nonprofit in Seattle educating the public about the Japanese American incarceration.

At Densho, Ikeda and his staff spent decades collecting oral histories.

Now, with only a few thousand survivors left, the focus is shifting to how to tell those stories creatively, Ikeda said.

In 2020, Densho launched a podcast, “Campu,” from the perspective of a brother-sister duo talking about their great-grandparents.

The organization also helped create an exhibit at the Bellevue Arts Museum in Washington, with Japanese American farmers describing their incarceration through augmented reality on visitors’ smartphones.

Facial recognition, machine learning and data scraping may be in Densho’s future, Ikeda said.

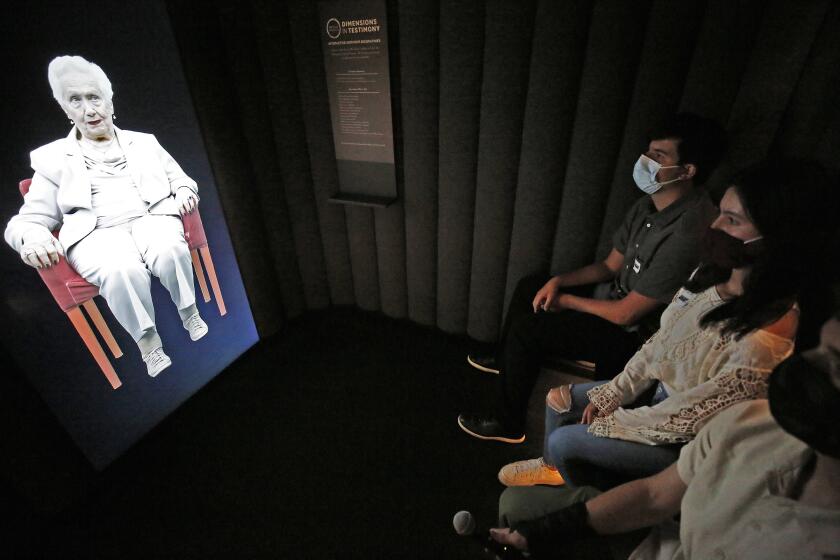

At the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo, a survivor who also served in the U.S. Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team speaks with visitors.

The survivor, Lawson Sakai, died in 2020. But the previous year, the museum had recorded him answering more than 1,000 questions.

With the help of artificial intelligence, a lifelike video image of him responds appropriately to visitors’ queries.

The AI survivor exhibit was modeled after a similar one at the Holocaust Museum Los Angeles.

The Jewish community faces similar challenges of preserving memories as fewer and fewer survivors remain.

Visitors can have a lifelike conversation with a holographic image of Holocaust survivor Renee Firestone, 97.

Those exhibits are “about inquiry, using technology to provide a way into an interrogation of the testimony that allows people to be curious,” said Kori Street, executive director of the USC Shoah Foundation, which created the exhibit.

The “wow” factor of new technology appeals to younger generations. But simply displaying historical artifacts, like those from the life of a Japanese American teenager killed in combat in Northern Italy in 1945, is important, too, said Clement Hanami, JANM’s art director and vice president of exhibitions.

“As a museum, real objects for us are very important,” Hanami said. “Trauma of the whole experience is a fragile thing, and it can be overshadowed by the spectacle. ... It’s important for us that the analog is not overlooked by the entertainment.”

Activists also want to ensure the preservation of the 10 concentration camp sites in remote locations around the western U.S.

They notched a victory this week when the U.S. Senate voted to designate Camp Amache in Colorado as a historic site. The bill still needs to be approved by the House and signed by President Biden.

“The significance is that we are moving toward telling a fuller story of our country,” said Tracy Coppola, the Colorado senior program manager for the National Parks Conservation Assn. “Just knowing the Amache site will be protected in perpetuity, for the current and future generations, brings a lot of hope to our country.”

In Northern California, a proposal to fence off the Tulelake Municipal Airport has activists up in arms.

The airport is built on the site of a camp for Japanese Americans who did not swear loyalty to the U.S., and the activists would like to relocate it. The fence is designed to keep out wildlife but would also deter visitors.

“We feel like this would be equivalent to putting a fence around Gettysburg,” said Barbara Takei, a member of the Tule Lake Committee.

Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in a U.S. camp during WWII are shedding the stigma and reclaiming their stories

Preserving the legacy of the incarceration and educating people about it remains an uphill battle at times. Bruce Embrey, who chairs the Manzanar Committee, worries about the controversy over critical race theory.

If school districts ban lessons about the country’s racist past, teachers might not be able to discuss the Japanese American incarceration and its legacy.

“It’s one thing for the victims not to speak about it,” Embrey said. “It’s another thing for the U.S. government’s education system to completely whitewash what they did.”

For Richard Murakami, 90, who was 10 when he arrived at the Tule Lake incarceration camp, the traumas his family kept hidden have still been emerging in recent years.

In 2016, his brother Dan told him about a visit to Tule Lake with their mother decades ago.

She never talked about their time at the camp. She didn’t want her sons to grow up with prejudice against anyone.

But when they reached the site of the camp that day in 1952, Dan recounted, she started crying and could not stop.

“Seventy-one years after camp — this was the first time I learned my mother led a tough, unhappy life while we were incarcerated,” Richard Murakami said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.