Rainey Renwick, 13, wanted to know what life was like in Auschwitz.

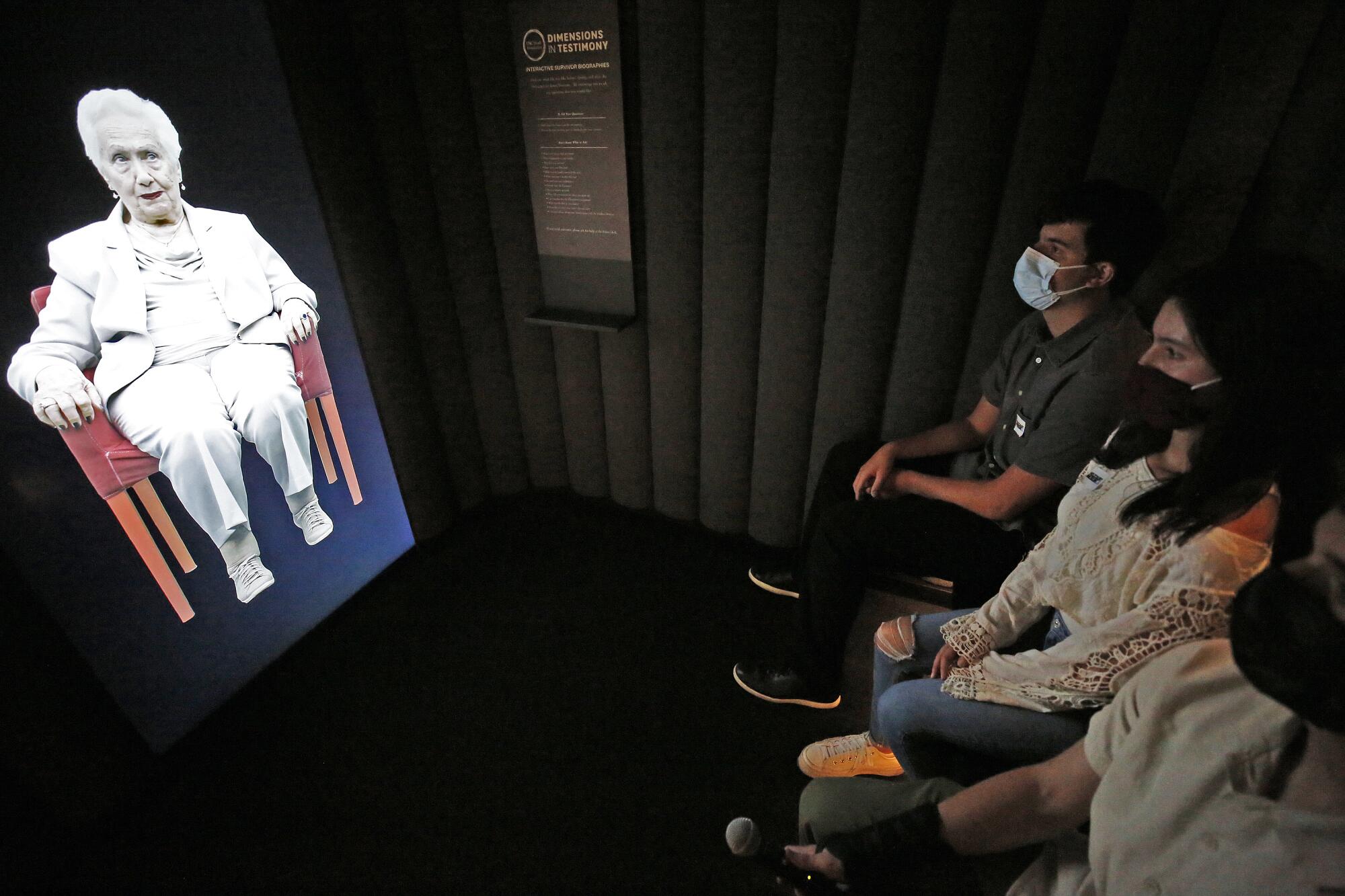

The white-haired woman on the screen, two-dimensional but remarkably lifelike, answered.

She recalled the barbed wire, the cold, wet wood of the barracks where she slept, and those around her who succumbed to pneumonia.

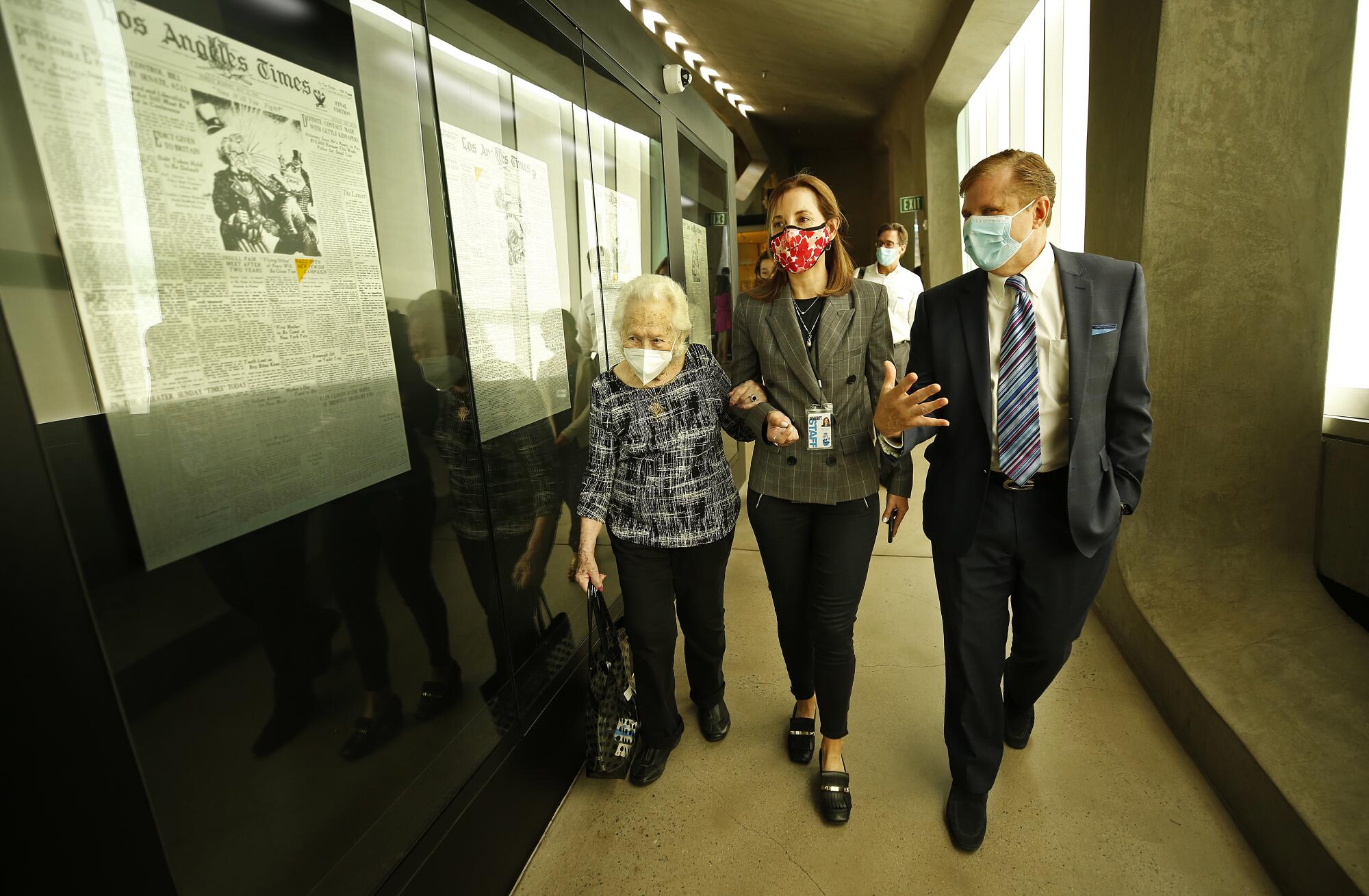

The holographic likeness of Holocaust survivor Renee Firestone, 97, is part of a new exhibit at the Holocaust Museum Los Angeles, which reopens on Saturday more than a year after the pandemic forced museum doors closed.

At a preview of USC Shoah Foundation’s “Dimensions in Testimony” exhibit earlier in the week, Renwick and other children peppered Firestone’s image with questions. The permanent installation allows visitors to have a lifelike conversation with one of the oldest Holocaust survivors in the world.

“Why did you survive?” asked Renwick’s sister, Kensi, who is 10.

“Do you ever have nightmares?” another girl asked.

The digital rendition of Firestone, sitting in a chair and dressed in a white pantsuit, almost always had an answer. When she didn’t, she would furrow her brow.

“I still don’t catch what you are asking me, so could you ask me another question?” she said.

Firestone herself — the real Firestone — sat nearby watching the holographic installation converse easily with the children.

To build the exhibit in 2015, Firestone answered more than a thousand questions in front of more than 100 cameras. The technology picks up keywords in visitors’ questions and cues up a response.

Indoor museums in L.A. County were permitted to reopen in March as coronavirus cases declined and vaccination efforts ramped up. The Holocaust museum held off on reopening until this month, in part because of budget issues as donors reduced or shifted their giving.

During its hiatus, the museum offered virtual tours to 30,000 students from places including Alaska, Wisconsin, Mexico and Australia, expanding its reach to places where Holocaust education is relatively sparse, said CEO Beth Kean.

As it opens its doors on Saturday amid a surge in the highly contagious Delta variant, the Holocaust museum is requiring tickets to be purchased in advance. Visitors must wear masks and are encouraged to stay six feet apart.

“Hopefully we won’t run into any problems,” Kean said. “We’re just going to have to take it day by day.”

Founded by survivors in 1961, the Holocaust Museum Los Angeles is the oldest of its kind in the country. It rented space for decades until finding its permanent home in 2010 at Pan Pacific Park.

Its new, permanent installation was developed by the USC Shoah Foundation, founded by Steven Spielberg in 1994 to document the stories of those who survived the Holocaust, or Shoah. The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center also supported the installation, which is the only one of its kind on the West Coast.

Shoah Foundation researchers have found that students are comfortable asking personal questions of a virtual Holocaust survivor that they might shy away from in person. “Many students are afraid to hurt a survivor’s feelings. They realize they went through so much trauma, and they don’t want to ask hard questions,” Kean said.

Firestone’s answer to why she survived: “My survival, I think, was pure luck,” her image said, after a pause. “I don’t remember doing anything to save my life.”

Firestone was born in Czechoslovakia in 1924.

Her mother was killed in the gas chamber on arrival at Auschwitz.

Her younger sister, Klara, was also killed in the gas chamber. Her father died of tuberculosis four months after liberation. She and her brother, Frank, reunited in Budapest shortly after the war.

Firestone met her late husband, Bernard, in Prague, where they had their only daughter, Klara. The family moved to Allentown, Pa., in 1948. Firestone became a fashion designer — something she had dreamed of at Auschwitz. Some of her pieces are now in the permanent collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Eleven million people were killed in the Holocaust. A majority of their names and faces have been lost to history.

Firestone’s story — the story of genocide, its victims and perpetrators — will outlive her. It’s a fact that leaves her with complicated feelings.

So many others will be forgotten, she said, sitting in an exhibit room emptied of visitors.

“I just feel lucky.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.