LAUSD shows its best to new Supt. Alberto Carvalho, who pledges to deliver more of it

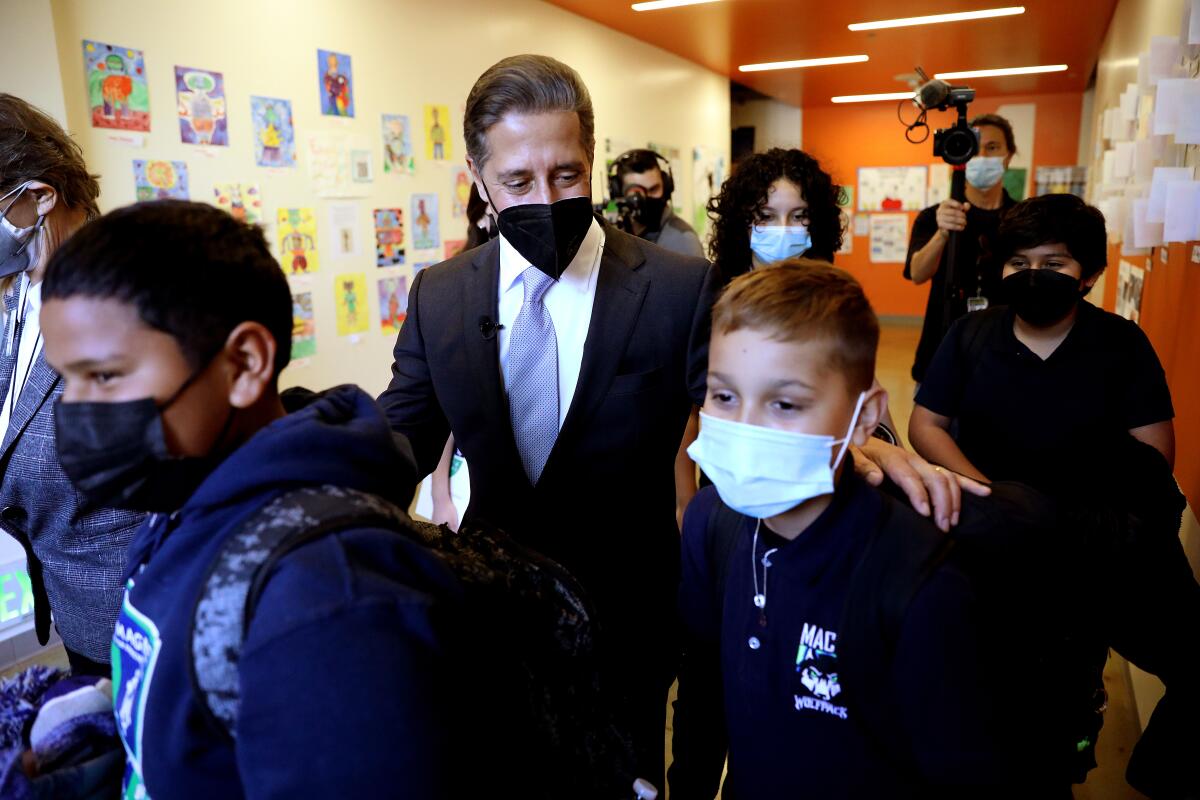

Over a two-day whirlwind tour, newly arrived Los Angeles schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho dashed around the vast system sampling the best that L.A. Unified has to offer — and repeatedly pledged that more high-quality schooling would be nurtured into reality because, he said, more is urgently needed.

He visited a parents center and called for parents to be “dangerous in a good way,” painted with a preschooler, floated an unusual student recruitment idea and fleshed out more of an anticipated 100-day plan.

He also said he is doing some homework: “I’m looking specifically at attendance patterns, proficiency realities specific to language arts, reading, mathematics, as well as the temperature on the social and emotional well-being” of students, drilling down into “every single ZIP Code, every single area” of the sprawling district.

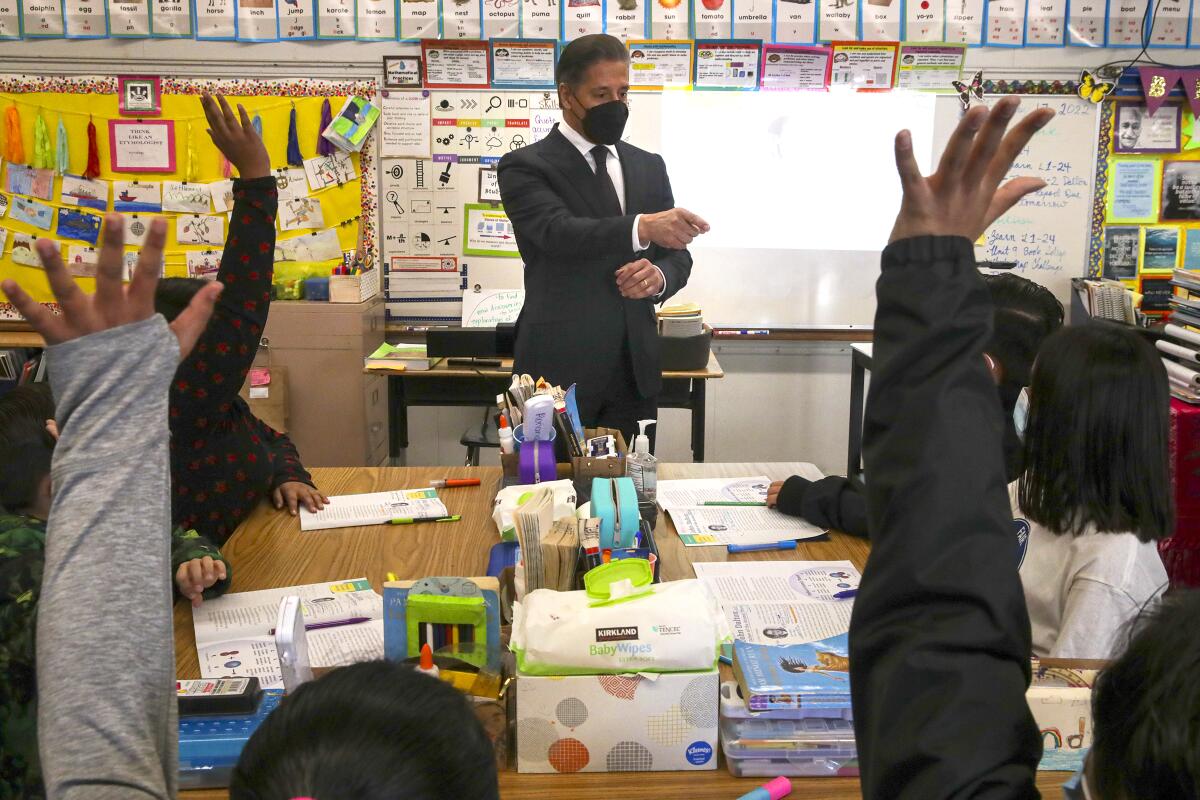

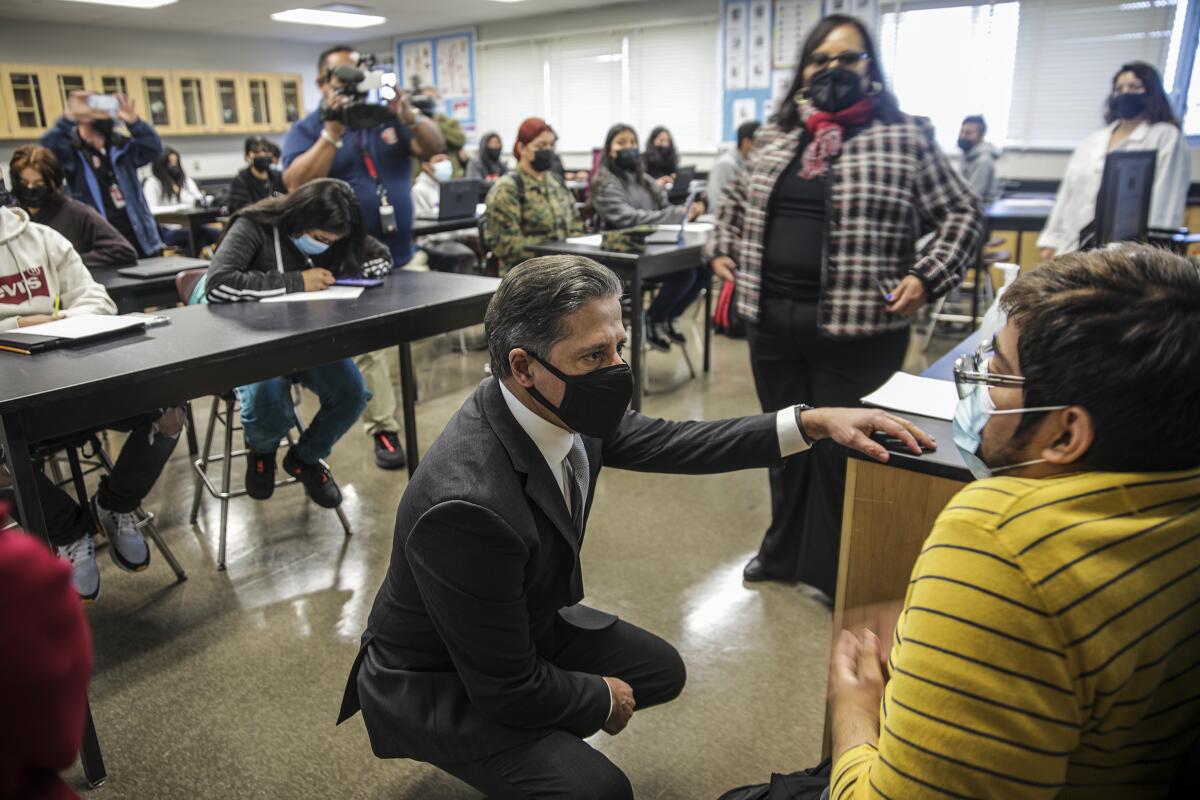

And at each stop and classroom, he queried teachers about the learning objective at hand — and asked teachers, principals and others about what he could do to help, signaling a hands-on management style.

This was his first week at the helm of the nation’s second-largest school system after serving more than 13 years as the head of Miami-Dade Public Schools, the fourth largest.

This week Supt. Alberto Carvalho took charge of Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district. His record in Miami was one of progress and unfinished work.

At the Miller Career and Transition Center in Reseda, he sampled biscotti from the bakery, where students with moderate to severe disabilities can matriculate after completing the 12th grade. The school system can serve these students until they are 22, and the staff at Miller uses this extra time to teach work habits and specific job skills in simulated but fully functional versions of a bakery, coffee shop, media center, farm and auto-detailing station.

Student Paloma Hernandez, 21, walked Carvalho through the process of washing his hands and putting on an apron and gloves to participate in sanitary food preparation. She told him she loved learning the work of the bakery.

He also made sure to ask Principal Tim Sweeney what he needed.

Sweeney said he could use more business partners to provide internships and ongoing jobs to his students. Carvalho promised a high-profile outreach.

Teacher Elizabeth Peña at Fair Avenue Early Education Center in North Hollywood said she wants a nature-activity program for her school — a specially designed area with minimal plastic or asphalt and activities involving plants, sand, water and mud.

In the meantime, Carvalho cheered on two children net-fishing in a tub for plastic toys. He asked them about colors and shapes and painted on a giant easel with pig-tailed Jailani Torres. She opted to create a black blob; he a blue smiley face.

As at many schools, enrollment at Fair Avenue has dropped sharply in recent times, at least partly due to the pandemic. That brought an idea to mind for Carvalho.

New LAUSD Supt. Alberto Carvalho must face students’ academic and emotional setbacks from the pandemic and long-term financial and enrollment worries.

What if every newborn in L.A. Unified were presented with a mock-up of a high school diploma? he said. Start recruiting students and getting families focused on education literally from Day 1.

At one school he said that parents needed to be “dangerous in a good way.” Then, in a later stop at the parents center of Garfield High, in East L.A., he elaborated on his goal of creating a cadre of parents who would demand excellence, just as parents do in more prosperous areas.

“Every moment we wait, every minute we wait, for those who believe that systemic educational reform will take 10 years — no, we can’t,” Carvalho told them. “Because if we say that and accept that, the question that should be asked and answered by somebody smarter than me is: How many kids are you willing to lose?”

Parents at all campuses need to be engaged, he said, and he’d push for a Parent Academy to accelerate that process.

“If you believe in the journey, and the plan: join,” he said to the group. “Don’t just join with: ‘Yes, I’m with you.’ Really join. Show up. Speak up. Step up. Because the forces against sometimes doing that which is right for kids can be powerful.”

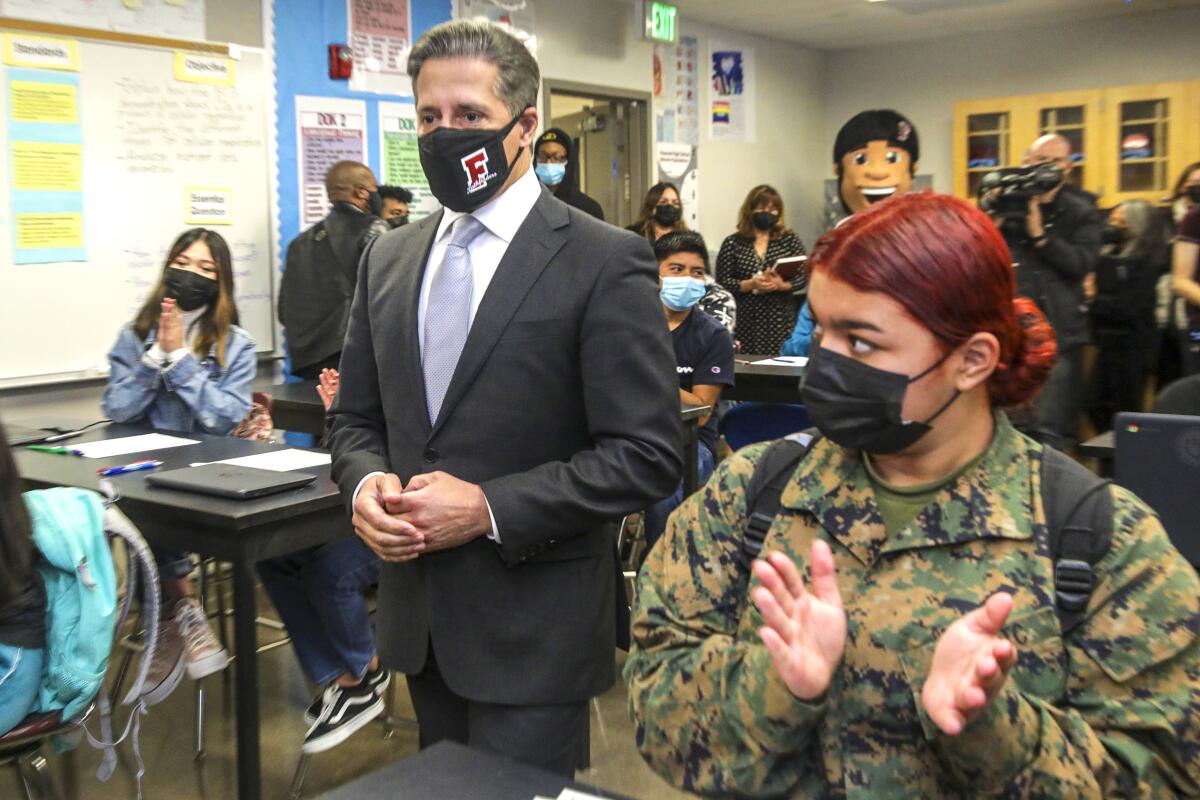

At Fremont High, in South L.A., Carvalho previewed elements of a soon-to-be-unveiled “100 Day Plan.”

This early agenda, he said, will include a review of pandemic recovery efforts already underway as well as evaluating short- and long-term spending. He noted that the pandemic relief dollars that flooded the nation’s second-largest school system are only temporary “and we need to once again have a vigorous discussion about the individual needs of students, particularly the most fragile students and align the resources to their individual needs.”

Standing in front of Fremont’s towering fountain, Carvalho praised an array of accelerated programs being pushed by Principal Blanca Esquivel. Then, the schools chief, who taught science early in his career, strode inside to briefly take over a biology class. The student response was muted until Carvalho began speaking in Spanish — it turns out the class was filled with English learners.

The superintendent talked a few minutes about cellular respiration — students listened politely — and then shifted into asking about college and career plans. These students have them: doctor, surgeon, nurse, architect.

Watching nearby was school board member Tanya Ortiz Franklin, who praised the principal and staff but also noted that only a third of Fremont students are on track to be eligible for a four-year state college.

“Generally, about half of our kids are eligible,” Franklin said. “Here, it’s much less. And while there are so many things happening that are great in the classroom, and I hope he’ll see that, there’s a lot of structural things we need to do.”

The Maywood Center for Enriched Studies was presented as a recently opened school created on the model of the long-running Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, or LACES. Unlike LACES, students don’t enroll at MaCES in large numbers from all over the district. But there is a waiting list of 550, and more schools like this are needed, said board member Jackie Goldberg.

“We have a bureaucracy that doesn’t always see the opportunities,” Goldberg said. “And sometimes new leadership helps them see those new opportunities.”

In a roundtable with MaCES students and staff, Carvalho emphasized the importance of high-quality choices.

“There are these great, great programs and great schools, so why not everywhere?” he said. “If it’s good for some, it’s good for everyone — for all.”

The choice at Castelar Street Elementary School in Chinatown is dual-language classes in Mandarin and English.

In one classroom, Carvalho sat down next to a second-grader learning to write words in Mandarin.

“This is apple,” the student said, pointing at a picture and saying the word for apple in Mandarin.

Carvalho repeated it back.

“You are a great teacher,” Carvalho said as he shook his hand. “Thank you for teaching me.”

Times staff writer Melissa Gomez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.