Supt. Alberto Carvalho won high marks in Miami, but can he move L.A. Unified forward?

Late last year, Supt. Alberto Carvalho gathered with his Miami-Dade principals to review disappointing data on the impact of the pandemic on student learning.

Miami-Dade has long taken pride on its significant strides toward improving academic achievement. But the data showed big dips in English test scores and even bigger drops in math, particularly for students of color.

One of Carvalho’s biggest accomplishments during his 13-year tenure was being undermined. No school in recent years has gotten an F under Florida’s grading system for measuring school quality and only a few received Ds. Although Florida did not require school grades during the 2020-2021 school year, if marks had been given, nearly 40% of Miami-Dade schools would have gotten Ds and Fs, the district’s data showed.

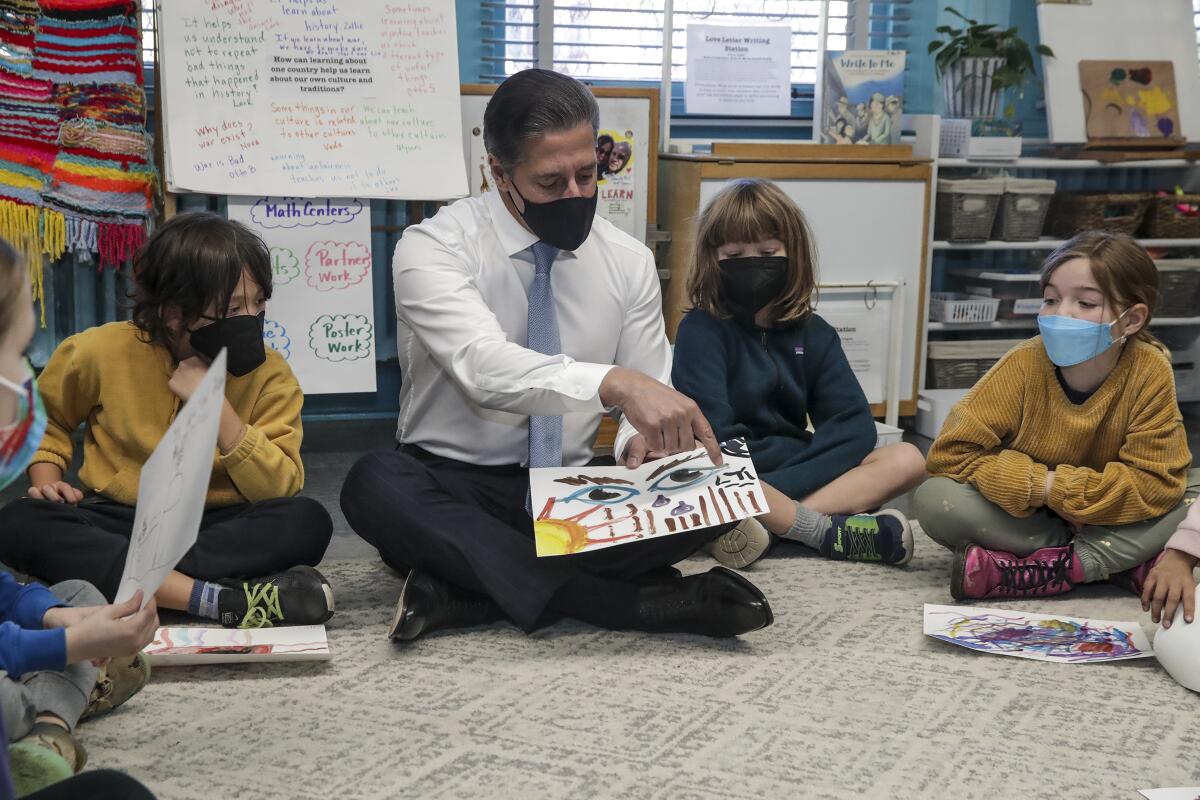

This week, Carvalho takes over as superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District and the high-stakes challenge to his Miami legacy is the same one he now confronts in L.A. — except on a bigger, more complex scale. Pandemic-related student achievement has deeply suffered at a time of declining student enrollment. Academic recovery has been stymied by shortages of teachers and other staff, a surge of student absences and the fight to keep schools running amid relentless crisis.

To understand Carvalho’s leadership style and how his experiences in Miami might carry over in Los Angeles, The Times reviewed public records and spoke with educators, experts and community members in Miami and Los Angeles about some of his major initiatives as schools chief. Carvalho also spoke about them with Times reporters for more than two hours in two interviews.

A picture emerges of an exacting, hands-on leader who raised Miami-Dade’s profile nationally and pushed schools to specialize to compete with private and charter schools. He was acutely focused on testing and other data to improve school and student performance. And, like education leaders across the country, he was still struggling to close the achievement gap, particularly for Black students, when he left.

In interviews he is detail-oriented and thorough, presenting slide shows and bar charts to convey his record in Miami as one of sustained progress over his tenure — even as he acknowledged that he wished he had done more early on to boost the achievement of some of the neediest students. And he expressed hope that he would be able to build on his track record in Los Angeles.

That principals meeting in November offered insight into a key way he approaches problems — by insisting that administrators become intimately aware of test scores and other data points to keep school performance up, said Gisela Feild, administrative director of the district’s data analysis office.

“That meeting was called ‘Dream Big’ because we needed to dream big to actually recognize the impact,” Carvalho said. “I was very concerned.”

‘One size fits none’

When Wioletta Bublik’s son was accepted a few years ago at iPrep Academy, one of Miami’s premier magnet schools, she felt like she “actually won the lottery,” she said. There were hundreds of students on the waiting list at the time for the technology-focused school. Carvalho was an active campus presence serving in a partly honorary role as principal with day-to-day operations handled by vice principals.

The school was part of an explosion of magnet schools under Carvalho’s tenure, reflecting his belief that districts should offer families a menu of options. “One size fits none,” he often says.

“Magnets before Alberto were kind of like a sleepy thing,” said Miami-Dade County commissioner and former school board member Raquel Regalado. “He turned it into a PR event. He would roll out the programs like Johnson & Johnson rolls out a product and everyone would scurry to get the application.”

He states proudly that about 75% of students in Miami-Dade have chosen the school they want to attend. Parents choose from among magnets, career academies and independently run charter schools, which enroll more than 70,000 students.

“The tsunami of choice is upon us,” Carvalho said, using one of his frequent catchphrases. “You can complain about it, stick your head in the sand and be washed away by it.”

Or, he said, “you can outcompete it.”

L.A. Unified already has magnets and an array of other “choice” programs and considers itself a national leader in this domain. In addition to the more than 112,000 students attending charter schools, more than 160,000 students have chosen magnets, dual-language schools, programs for gifted students and other offerings. Combined, that accounts for about half of enrollment.

Carvalho said he wants to expand choice options in L.A. guided by two elements: What schools have greater demand than available seats? And do students have nearby access to such programs?

“That’s where I talk about demand-driven reform,” he said. “What are parents choosing? What are kids choosing? And if we need more of that, let’s launch it.”

‘Data is our superpower’

In 2010, about two years into his leadership of Miami schools, Carvalho hired William Aristide as principal of Booker T. Washington Senior High School. As Aristide puts it, Washington Senior High is “one of the toughest schools in the state of Florida academically … in a very tough neighborhood.”

Carvalho had created an Education Transformation Office to improve performance of the district’s “persistently lowest achieving” schools. Booker T. Washington had an F grade under the state’s school grading system.

Florida’s high-stakes accountability system gives schools letter grades based largely on standardized assessments. Carvalho said it unfairly penalizes schools that serve students of color and low-income families. Nonetheless, he leaned into the system, creating a culture in which everyone from principals to students would be keenly aware of testing and other school data.

Carvalho is “evidence-based” and meticulous and expects principals to be the same, said Angel Rodriguez, family liaison officer for the school district. He would call up principals out of the blue with detailed questions about utility bills, academic testing and the conditions of classrooms and buildings.

“A principal better be a master” when Carvalho calls, Rodriguez said.

Carvalho said he makes every decision “on the basis of developable data.”

“Data is our superpower, how we access it, what we measure and the opportunities that it creates for us to be able to pivot and recalibrate our approach on the basis of progress monitoring,” Carvalho said.

The superintendent and his team met with Aristide and principals of other targeted schools once a quarter for “Data/Com,” where school leaders are expected to give detailed reports on test scores, attendance and other data.

“We would literally break down [data] teacher by teacher. I could spit out data from each of our teachers in our building,” Aristide said.

Carvalho would ask what resources the school needed to improve its numbers, Aristide said.

“He’d also hold me to making sure I did what I said I was going to do,” Aristide added.

“I knew it was becoming successful when our students started to speak on their data,” Aristide said. “They could tell you exactly what they scored on their reading, their math.”

Miami-Dade students are encouraged to “own their own data,” Carvalho said. Students and families will know “for example, that they may be, as far as reading is concerned, for whatever reason, maybe six months behind where they should be or a year, a grade level behind.”

“The importance of the data is really to assist us in what I believe is the most effective way of teaching, which is personalizing the education for the student ... and being very honest and transparent about the progress that’s being made,” Carvalho said.

Most teachers supported the changes, Aristide said. Those who didn’t, “ultimately, some of them realized this was not what they wanted to do and they were able to go work elsewhere,” he said.

The school’s graduation rate rose from 69% his first year to 95% a decade later. Its state-issued grade improved from an F to a C, which it maintained most years through 2018-2019, the last report before the pandemic.

The system that Carvalho relied on in Miami was one in which centralized data formed the foundation for the oversight of schools.

In Los Angeles, previous Supt. Austin Beutner pushed for local autonomy, with more authority handed to regional districts and principals. LAUSD schools, however, are not generating consistent, comprehensive data. The analysis of student achievement data was further complicated when the state put universal grade-level testing on hold during the pandemic. School board members at recent meetings have expressed frustration over the limited information available to them and the public.

Meanwhile, the teachers union has criticized the district for overtesting that steals too much classroom learning time.

When asked whether he thought Los Angeles should have more centralized systems, Carvalho was guarded, saying he did not want to speak about specific plans before talking to the board. But, he said, “there needs to be a fair balance between autonomy, which generates good results, but also a unified sense and understanding of that which is essential, indispensable and important.”

L.A. school board member Nick Melvoin said he was impressed with Carvalho’s production in Miami of a five-year strategic plan, which, in L.A., would provide a needed yardstick for progress.

Data aside, Aristide said, the superintendent also cared deeply about the broader well-being of students, which was especially important at a school that lost students to drugs and gang violence.

“I cannot remember a moment when the superintendent was not at the funeral with me, where he was not visiting homes with me,” Aristide said. “He was there not just for a cameo appearance. He was there for quite some time. Talking to the parents, praying with the family. It was huge for me. And even bigger for the families.”

‘We will tackle historic disparities’

Standing in a gym at the Edward R. Roybal Learning Center for his first L.A. news conference in December, Carvalho pledged to do something that has eluded the city’s school leaders for decades: “We will tackle historic disparities, social inequity. We will tackle achievement gaps that are so prevalent across this country,” he said.

That focus is also front and center for many board members, who are acutely aware of how the pandemic worsened existing gaps — and expect him to bring his rare record of stability to Los Angeles.

“He was clear-eyed about the historical challenges that Los Angeles has faced and the inequities exacerbated by the pandemic, but confident that these challenges could be overcome with the right team and supports in place,” said L.A. Board President Kelly Gonez.

Board member George McKenna, who represents South and Southwest Los Angeles, was more blunt: “I want to see his unapologetic focus on closing the gap.”

Carvalho said his record shows he can move L.A. Unified quickly in the right direction.

The graduation rate in Miami — where more than 73% of students are from low-income families and more than 73% are Latino — was about 90% for the 2020-2021 school year. The graduation rate in Los Angeles is about 83%.

Miami also has outperformed Los Angeles, along with many other big city districts, on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which is known as the nation’s report card and relies on testing a sampling of students.

But Miami has not come close to eliminating its achievement gap.

For example, in 2018-2019, the last school year before the pandemic, there was a 37 percentage-point proficiency gap between Black and white students in grades 3-10 on the state’s English language arts assessment. That’s about 4 percentage points smaller than it was four years earlier. The numbers were similar in math.

Board member Steve Gallon, a former Florida principal and a onetime district superintendent in another state, said he worried that the district’s lofty graduation rate and improved school grades mask serious challenges.

“Letter grades can be quite deceptive,” Gallon said at a meeting last year. “If you look at the letter grades, it doesn’t get behind the 50% plus not being proficient for Black and Hispanic students, which Black and Hispanic students represent the majority of this school district.”

In the interview, Carvalho said that Miami has outperformed the state of Florida for gains with Black and Latino students. But, he added, the degree of progress is not enough.

“I absolutely believe that the strategy of Miami-Dade has worked, but not as fast as I would like it to,” he said.

Matters such as providing students with expanded learning opportunities — additional time before school, after school, Saturday and winter academies and summer school as well as expanded preschool opportunities — are key to closing gaps, Carvalho said.

“Were I to do it all over again, I would’ve done it differently,” he said, referring to the expanded offerings. “And that’s exactly the type of learning that I’ll be carrying with me to L.A.”

Times staff writer Melissa Gomez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.