Minimal damage in Southern California after tsunami advisory in the West

The eruption of an underwater volcano Saturday in a remote corner of the South Pacific touched off a powerful tsunami that roared across a large swath of the globe, putting millions of people from New Zealand to Canada on alert and forcing the closure of beaches and harbors in California and along the rest of the West Coast.

Two people drowned off the coast of northern Peru due to unusually high waves but elsewhere there were no immediate reports of deaths, serious injuries or widespread property damage. The hardest-hit area of California appeared to be Santa Cruz Harbor, where the tsunami waves rushed in at high tide, flooding a parking lot and streets.

“The boats are still sitting pretty good,” said boat owner Scott Sommers, who watched from a railroad bridge over the harbor Saturday morning as the surge buffeted the vessels.

Fears of a Pacific Rim disaster began Friday around 8 p.m., when the Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai volcano erupted in waters about 40 miles from Tonga’s capital. The plume of ash and smoke flared 12 miles in the air, bursting on satellite feeds like a mushroom cloud and gripping the attention of meteorologists and tsunami scientists.

Close to the epicenter, Tonga almost immediately experienced flooding of streets and buildings. Communications with the archipelago nation of about 105,000 have since become sporadic, and the full impact is not known.

Hawaii saw surging tides of about 2½ feet, reports of a boat lifted from its moorings and what authorities described as “minor flooding.”

Watching the water levels from Palmer, Alaska, were scientists at the National Tsunami Warning Center, a government agency responsible for alerting local officials to close coastlines and evacuate communities. The advisories the center issues are almost always triggered by underwater earthquakes, and its computer models are based on seismic events, not volcanoes.

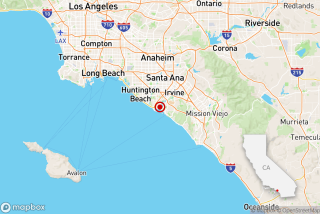

The Tsunami advisory had largely been cancelled by 9 p.m. along the California coast, including in Los Angeles and Orange counties. However it remained in effect in San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties.

“It’s really different than what we are designed to do,” said Dave Snider, the center’s tsunami warning coordinator, who, like other officials, said he couldn’t recall a previous instance of volcanic activity prompting tsunami worries in the United States. “This is a really significant event.”

At 4:53 a.m. Saturday, the center issued a tsunami advisory for surges of up to 3 feet for the entire Pacific Coast, from the Mexican border to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. Advisories, as opposed to the more severe warnings, do not require people to evacuate to higher ground but only to stay away from the shore.

Police and lifeguards were on the sand before sunrise in many California communities in an effort to keep surfers, kayakers and swimmers out of the water.

“Fortunately we got there pretty early … and I don’t think we had to chase anybody away,” said Lt. Nick Nicholas of the Seal Beach Police Department in Orange County.

California is hit by about one tsunami a year, but most are barely noticeable. That said, if you live or work near the water or ever visit the coast, you should know what to do if there’s a big earthquake or a tsunami warning.

In Santa Cruz Harbor, the harbor patrol and boat owners went from vessel to vessel rousing people to evacuate. During a 2011 tsunami caused by a Japanese earthquake, the harbor sustained more than $20 million in damage.

Some fearful of damage to their boats opted to ride out the surge in the open sea. Other owners gathered in a harbor parking lot or on a railroad bridge overlooking the harbor to witness the fate of their boats.

Gordon Rudy, a real estate agent who keeps a 28-foot cabin cruiser boat at the harbor’s U-Dock, said he had reason to be worried after a previous boat sustained nearly $30,000 in damage in 2011.

But the tsunami waves that began Saturday around 8 a.m. were “really, really smooth,” he said, “not like in 2011.”

Sommers, his harbor neighbor, who owns a 32-foot boat, concurred, describing the water in 2011 as rising steadily by as much 8 feet and then receding just as rapidly: “Like high tide and low tide happened in two or three minutes,” Sommers said.

Those watching from the shore Saturday said they saw no sign of damage to boats, though water flooded into nearby roads and a parking area.

“With the water still being a pretty high level, it’s hard to assess the damage right now,” said Ashley Keehn, public information officer for the Santa Cruz County Sheriff’s Office.

The highest surge on the California coast was close to 4½ feet, recorded shortly after 9 a.m. near Avila Beach in San Luis Obispo County. Yet, in what became a common refrain Saturday, authorities reported little sign of the tsunami there beyond some debris washed into the bay.

By midday, the advisory had been canceled for parts of Alaska, and officials said they were expecting more cancellations as waters receded. Advisories had largely been canceled along the California coast by 9 p.m.

“Right now it looks like conditions are improving, ” said Snider of the National Tsunami Warning Center.

Beach openings would come too late for the Chan family of Bakersfield. The family left home for Newport Beach at 7 a.m. looking for no-cost entertainment for the children, fishing time for the father and, as mother Monica Chan explained, “some peace.”

Instead, they spent the morning waiting for access to the city’s pier.

“We didn’t know about the tsunami,” Monica Chan said. Her 8-year-old, Julieta, found an upside in incorporating a new word to her vocabulary. She described “tsunami” as “making me worry. It might take me far away if it blows closer.”

Newport and other shore areas of Orange County appeared to have escaped damage, with surge levels remaining below a foot and no sign of flooding, according to the sheriff’s department.

Harbor patrols and local authorities were going boat to boat on the water to warn mariners about remaining dangers from the tsunami.

“The major point of concern is for currents, particularly strong riptide currents,” said Carrie Braun, director of public affairs and community engagement for the Orange County Sheriff’s Department.

Though patrols kept many people from the water, some surfers could not be dissuaded.

At the Venice Breakwater, David Solomon was more worried about which of two short boards to use than the tsunami alert that popped up on his phone.

“I thought it was so funny that I grabbed a screenshot for my friends,” he said before heading into the water.

Another Venice surfer, Glen Alder, said he and several friends were disappointed the tsunami hadn’t made for bigger waves.

“We were hoping for a little bump, but that didn’t happen,” he said.

In Santa Cruz, Dustin Mulvaney saw waves splashing against cliffs. An environmental studies professor at San Jose State University, Mulvaney said the tsunami swell coincided with a high tide, and the breakers sloshed about 15 feet above the sand onto the stairs at Mitchell’s Cove Beach.

The waves were some of the biggest he’s seen in the past year. He said looking at them crash so high made him think about the need to prepare for sea-level rise and worsening storm surges.

“We have areas prone to earthquakes and fires,” he said, “and just having a tsunami added on top of all that makes you realize that we all live in kind of vulnerable places.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.