L.A. earthquakes have been unusually frequent this year, as Malibu temblor shows

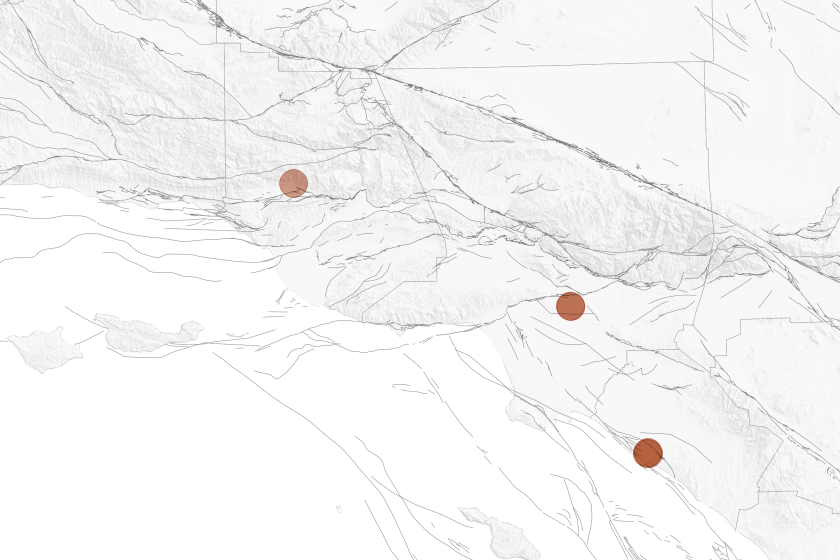

The magnitude 4.7 earthquake just north of Malibu on Thursday morning adds to what scientists say is an unusually active year for moderate earthquakes in Southern California.

The Malibu earthquake was part of the 14th seismic sequence this year in Southern California with at least one magnitude 4 or higher earthquake, said seismologist Lucy Jones, a Caltech research associate.

The observation is not necessarily an indication that a large, damaging earthquake is around the corner, scientists said. Some researchers have offered dueling theories — some say earthquake activity increases in a region before a large earthquake, others say seismic activity decreases before a large jolt. So the recent activity does not offer any hint of when the next large, destructive temblor will occur, said Susan Hough, a U.S. Geological Survey seismologist Susan Hough.

Monday’s magnitude 4.4 quake that rattled Southern California is believed to have struck on a well-known and dangerous fault system known as the Puente Hills thrust fault system.

But it is a reminder that Southern California has been in a seismic drought, so to speak. The last major seismic event underneath a highly populated area — the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake — is now 30 years old. And the seismic drought won’t last forever.

Over the last 65 years in Southern California, Jones said, there were an average of eight to 10 independent sequences of earthquakes that included at least one of magnitude 4 or greater.

In some years, there’s just one or two of those earthquake sequences; the highest previous tally was 13 in 1988. But this last year has broken a record for the last 65 years, with Thursday’s quake being the 14th seismic sequence with an earthquake of magnitude 4 or greater this year.

“So yes, this is a more active year than we’ve had in the past,” Jones said. But, she said, “we can’t quite say yet that whether or not that it is actually statistically significant to be seeing this.”

The latest quakes are “a really good reminder that the quiet of the last couple of decades is not our long-term picture, and we do need to be prepared,” Jones said.

Thursday’s quake struck at 7:28 a.m. and was centered in the Malibu Hills off Kanan Dume Road around Ramirez Canyon.

Malibu Mayor Doug Stewart and his wife were sitting at the breakfast table when they felt a jolt and heard warnings go off on their cellphones.

“It was a good jolt; it was right away — ka-bang!” Stewart said. “I’ve been through a lot of earthquakes after all these years here, and this was the closest that I’ve been to an epicenter.”

Stewart said he and his wife dived under the kitchen table when the quake hit.

“There was no question about table or no table,” he said, chuckling. “We looked at each other and dove.”

Apart from a few rocks on the road, Stewart said there was no damage in the city or reports of any injuries. The quake was rather timely, he said, as the city had scheduled a meeting to review disaster preparedness plans with partner agencies and volunteers.

“So we had a lot to talk about,” he said. “It was an unintended after-action review that was very timely and gave us an opportunity to discuss with our partners.”

There have already been a number of aftershocks, including magnitude 3.4 quakes at 8:40 and 9:37 a.m. And residents should be prepared for more.

“Earthquakes like to cluster up with other earthquakes in space and in time, and this earthquake is no exception,” said Morgan Page, a USGS geophysicist. In most cases, aftershocks are smaller and fade over time, but there is a 1 in 20 chance that, in the next week, there will be another earthquake of magnitude 4.7 or larger.

Earthquakes can reach up to a magnitude 8 in this area, Morgan said, which is actually “pretty standard for anywhere in California.” That’s because individual faults can link up with others in the same seismic event to form an even larger magnitude earthquake.

The epicenter of Thursday’s earthquake was closest to the Malibu fault, Jones said. Initial analysis suggests the quake had a 40% chance of being associated with the Malibu fault and a 46% chance of being associated with the Anacapa fault.

Earthquakes of this magnitude rupture only a relatively small section of a fault, perhaps only a few hundred yards. As such, these modest events can often happen on small faults that are not associated with faults that are much larger and mapped at the Earth’s surface.

“Moderate” and “light” shaking, as defined by the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale, was felt in parts of Malibu, Thousand Oaks, Agoura Hills, Calabasas and Westlake Village. Moderate shaking is felt by nearly everyone and can break windows and dishes; light shaking can rattle dishes, windows and doors; makes cracking sounds in walls, and can feel like a heavy truck has struck a building.

In Thousand Oaks, one resident reported the shaking lasting a few seconds, but a resident elsewhere felt about 12 seconds of rattling. There were also many people in Southern California who didn’t feel the earthquake.

Some of the strongest shaking was felt in western L.A. County — not surprising, Jones said, given the region’s proximity to the epicenter and because of the deep soft sediments underlying the surface in that area, which amplify shaking from earthquakes.

“Weak” shaking was felt over most of the Los Angeles metropolitan region, including downtown L.A.; Santa Monica; Long Beach; the San Fernando, San Gabriel and Antelope valleys; Orange County and the Inland Empire. There were crowdsourcing reports indicating that shaking was felt as far away as San Diego and Bakersfield.

People along the L.A. County coast felt notable shaking. Some people in Redondo Beach and Long Beach felt shaking for 10 seconds. In Redondo Beach, a person felt the shaking begin small and then intensify, but nothing fell from shelves.

Near Los Angeles International Airport, an apartment building in El Segundo shook and curtains swayed. Residents of El Segundo and Long Beach described feeling a shake and then a roll; in Downey, someone felt a rolling first and then a jolt. In Brentwood, the shaking sounded as if someone slammed a door shut, shaking the windows.

The earthquake startled anchors broadcasting live at KTTV-TV, which has studios just east of Santa Monica. “We’re having an earthquake right now,” the anchors said, followed by the sound of a rumble and an exclamation of “Whoa!”

While streaming on KABC-TV, the camera began to shake at the station’s Glendale studio before someone offscreen yelled out, “Earthquake!”

Having half a dozen earthquakes with a magnitude 2.5 or greater strike in a single week is not a common occurrence in Southern California.

Emil’s Bake House is a favored early morning stop of commuters streaming from the 101 Freeway to Malibu via Kanan Road in Agoura Hills.

Julius Speck was at the counter serving customers lattes, scones and vegetable juice when the windows and display cases rattled.

“I thought somebody dropped something in the back,” Speck said, pointing to the kitchen. “I was confused.”

The shaking lasted only a few seconds, and Speck said he took a deep breath and asked the next customer what they’d like to order.

California has not experienced a truly devastating quake in an urban area since 1994, so the trauma that comes with that kind of shaking has faded from memories.

Another earthquake in Malibu, a magnitude 4.6, was felt Feb. 9. That jolt’s epicenter was about six miles to the southwest of Thursday’s quake and probably wasn’t related to it, Page said.

Another cluster of earthquakes was reported over the summer in El Sereno, on Los Angeles’ Eastside, which occurred on the Puente Hills thrust fault system. The most recent was a magnitude 4.4 quake that occurred Aug. 12, which was enough to cause shampoo bottles to be knocked off a shelf at a Target store in Alhambra.

They were preceded by a pair of earthquakes in early June — a magnitude 3.4 on June 2 and a magnitude 2.8 on June 4 — as well as a magnitude 2.9 earthquake in the same area June 24.

The Puente Hills thrust fault system is the same overall fault network that produced the 1987 Whittier Narrows magnitude 5.9 earthquake, which killed eight people and caused some $358 million in damage. The Puente Hills system is capable of producing a magnitude 7.5 earthquake, which runs under highly populated areas of L.A. and Orange counties and could kill 3,000 to 18,000 people, according to the USGS and the Southern California Earthquake Center.

The magnitude 5.2 earthquake near Bakersfield was felt over a wide area of Southern California. Experts say there are several reason for this, including its size, time of night and the so-called ‘basin effect.’

The largest earthquake experienced in California this year was the magnitude 5.2 temblor that occurred Aug. 6. That was centered on rural farmland about 15 miles northwest of the unincorporated Kern County community of Grapevine near Interstate 5 and about 19 miles southwest of Bakersfield.

Another widely felt earthquake, a magnitude 4.9, struck on July 29. Its epicenter was in the Mojave Desert, about 14 miles northeast of Barstow, in San Bernardino County, and shaking was felt across Los Angeles.

Some residents were alerted Thursday by the earthquake early warning system, which is powered by the USGS’ ShakeAlert system. In Koreatown, residents got about two seconds of warning before shaking arrived. A free earthquake early warning system app, MyShake, can be downloaded from the iOS and Google Play app stores. Android also has an earthquake early warning system built into its operating system.

Areas close to Malibu have had stronger earthquakes in the past. On Jan. 18, 1989, a magnitude 5 earthquake occurred 8 miles southeast of Malibu Point, underneath Santa Monica Bay; several people were injured and items fell off shelves in stores and some windows were broken, according to the Southern California Earthquake Data Center.

On New Year’s Day in 1979, a magnitude 5.2 quake hit about 8 miles south of Malibu Point, notable because it struck during the Rose Bowl game between USC and Michigan. “Some of the fans in the stadium were alarmed by the shaking, but the game continued,” the Southern California Earthquake Data Center said.

Thursday’s earthquake moved in a horizontal, side-to-side motion, also known as “strike-slip motion,” Jones said. The other type of movement that can be felt in other earthquakes in Southern California are upward motions on a dipping fault.

Scientists urged people to fill out the “Did You Feel It?” crowdsourcing form on the USGS website to let officials know what intensity shaking they felt at their location.

The ShakeAlert system is operational statewide in California, Oregon and Washington, with plans underway to extend it into Nevada, said geophysics professor Allen Husker, head of the Southern California Seismic Network at Caltech.

On the C Line (formerly the Green Line) Metro train heading west toward the Crenshaw station Thursday, cars erupted in beeping as phones lighted up with warnings of the quake. Passengers reached for their phones or looked around in alarm, but the train continued forward, swaying as usual. Despite the instructions on their phones, no one dropped to the floor or sought cover under their seats. Shaking from an earthquake was not noticeable on the train.

It’s not unusual for people to feel varying levels of shaking, or none at all. If you’re sitting quietly, the duration of shaking you feel may be much longer than by someone who is moving. And being on top of soft sediment in valleys and basins, where shaking is amplified as it bounces around, can result in feeling longer shaking than if you were on top of bedrock.

The Los Angeles Fire Department, as well as Ventura County officials, reported no damage. The L.A. County Fire Department received no calls regarding the earthquake.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department locked down all of its jail facilities after the quake to do a damage assessment but quickly returned to normal operations after none was found.

In general, an earthquake must be at least a magnitude 5 to cause damage, if it’s a relatively shallow event, Jones said.

“It is a very good reminder to people that we live in earthquake country. And we need to take the steps that will help keep us all safe if a bigger earthquake does occur,” Hough said.

Times staff writers Keri Blakinger, Alexandra Del Rosario, Jon Healey, Meg James, Iliana Limón Romero, Samantha Masunaga, Luke Money, Joseph Serna and Richard Winton contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.