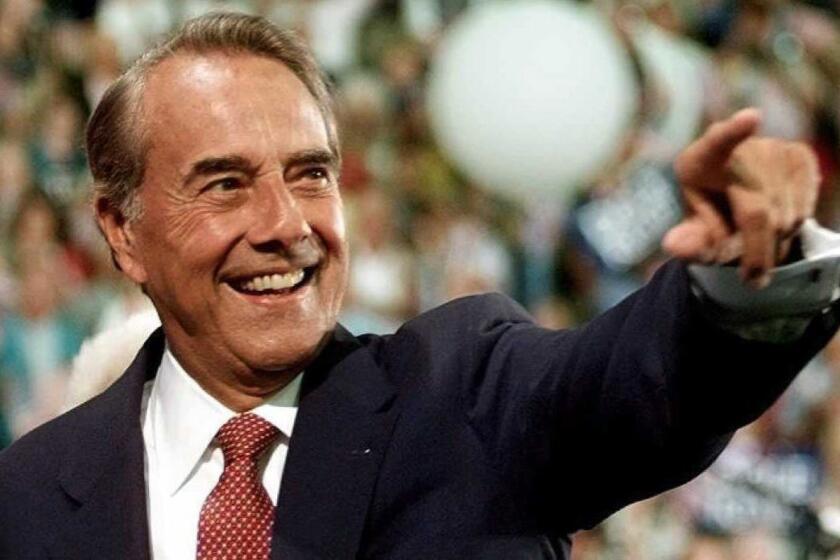

Bob Dole was known for his gut punch. But his gift for political compromise won him respect

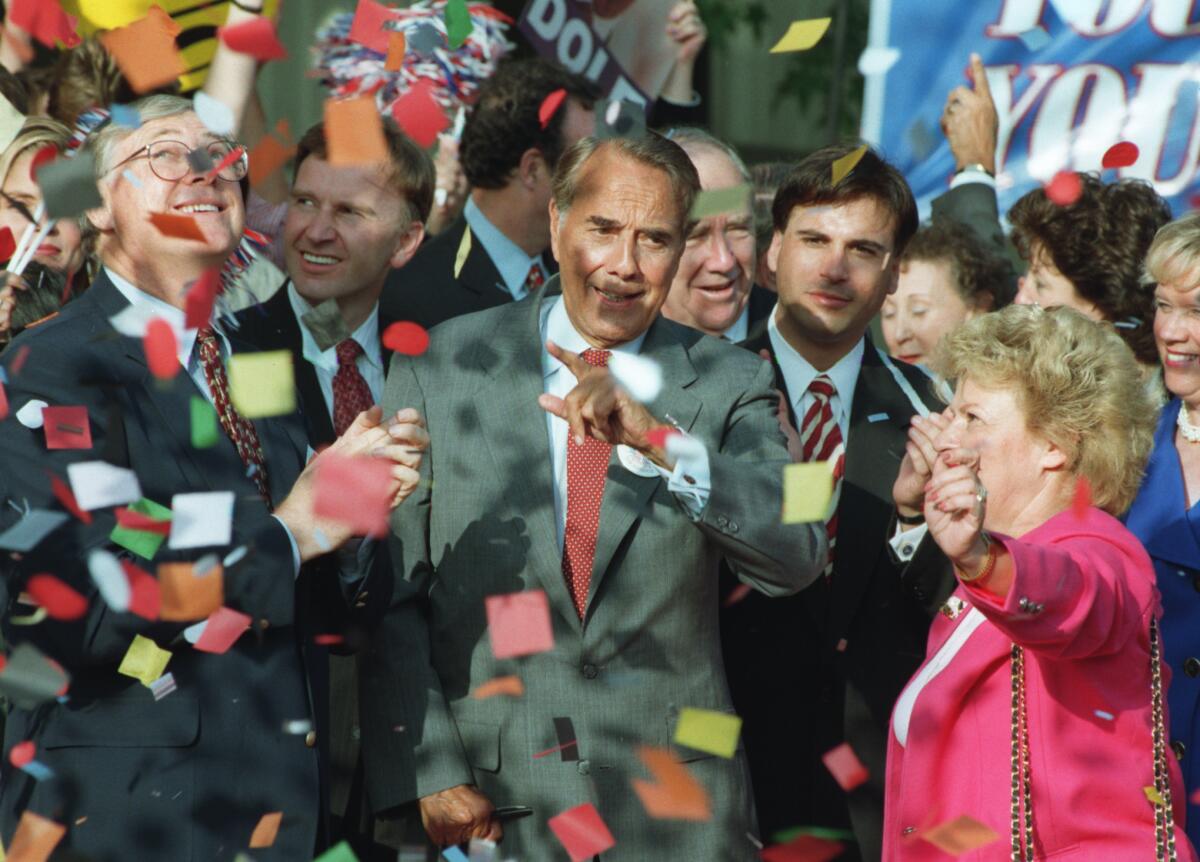

SACRAMENTO — For decades, Bob Dole wouldn’t talk about the war wounds that left him with crippling disabilities. But by his 1996 presidential race, he was opening up.

“There I was over in Italy on April 14, 1945, a young 2nd lieutenant…. Our job was to prevail, and we were prevailing, and I was leading a platoon and I got shot,” I heard him tell workers at a bomber parts plant in Pico Rivera during the ‘96 California primary.

“And I spent the next 39 months in and out of hospitals learning how to feed myself and go to the bathroom and walk and all those things we take for granted.”

Dole had been leading an infantry charge and just dragged a wounded radioman to safety when mortar fragments shattered his right shoulder and cracked several vertebrae.

He never regained the use of his right hand, and his right arm was virtually useless. His left arm was weak. It would take him an extra hour to get dressed every morning.

Aboard Dole’s campaign plane flying to San Francisco after the B-2 plant stop, I asked the Senate majority leader why for most of his life he hesitated to talk about the combat wounds.

“I thought it was a private matter,” he answered. “I thought people might think, ‘The guy’s looking for pity.’”

So, why now, I asked.

“I’m trying to break down this barrier between those of us in politics and the real people ... and their belief we’re just power hungry and insiders and we don’t care about them. We’ve never had any trouble in life. We just all ended up in Congress. Let ‘em know I’ve had a life too.”

A noble cause but not a promising one. It’s in the American DNA to cynically look down on politicians with suspicion. Actually, most are mixed bags of strengths and weaknesses like the voters who elect them. Like Dole.

Bob Dole’s body has been returned to Kansas for memorial services in his hometown and at the Statehouse.

He grew up on the Kansas plains, survived the war wounds, rose to the highest perch of the U.S. Senate, ran once for vice president and three times for president, and finally won the Republican nomination in 1996.

Dole died at 98 on Dec. 5. He’d been diagnosed with advanced lung cancer.

He was respected as a practical compromiser who worked with both sides to cut good deals for the country. But he also was denigrated as a gut fighter who hit below the belt.

In 1996, Dole was trying to smooth the hard edges on his reputation as a meanie.

The most infamous example of Dole throwing a low blow came during his 1976 vice presidential debate with Democrat Walter Mondale. I was sitting in the Houston auditorium helping to cover the debate for The Times and winced when Dole implied that Democrats were to blame for war.

“If we added up the killed and wounded in Democrat wars in this century it would be about 1.6 million Americans,” he said.

Mondale swiftly replied, “Sen. Dole richly earned his reputation as a hatchet man tonight.”

Later, Dole admitted he’d overreached and displayed his familiar self-deprecating humor.

“I went for the jugular,” he said. “My own.”

For decades he was at the center of Washington and the searing battles within the Republican Party.

After President Ford chose Dole as his running mate at the GOP convention in Kansas City, fellow Times reporter Bob Jackson and I spent several days in the VP nominee’s small hometown of Russell, Kan., interviewing relatives and friends.

Western Kansas was much like California’s Central Valley farm belt, except for fewer people and no enchanting Sierra Nevada backdrop. Lots of plain, hardworking folk.

We talked to Dole’s first wife, Phyllis, who expressed no bitterness about her former husband asking for a divorce after 24 years of message. They both remarried.

“A lot of things he did,” she told us, “he was proving to himself he could do them…. The competition of politics may have been a substitute for the athletics he missed” as a high school star.

In my 1996 interview, I asked Dole whether his disability had changed him personally.

“A little bit,” he replied. “It’s made me more sensitive.”

He added: “You can’t do anything about it, you might as well learn to live with it. And I think it makes you stronger in many ways. You understand not everybody’s perfect.”

I found Dole very pleasant to talk with — good natured, candid and gracious. No demagoguery or hatchet tossing.

Marty Wilson, who was Dole’s California campaign manager during the primary race he won easily, recalls him not being ruffled by personal attacks. A rare politician.

“I suspect that’s because what he had to overcome as a young soldier was so much more challenging than the silly crap that goes on in politics,” Wilson says.

Veteran strategist Ken Khachigian, who ran Dole’s California general election campaign, recalls the Kansan’s affinity for common people. The two were staying in Santa Barbara, and Dole asked where they should dine.

“I said, ‘There are a lot of fancy restaurants in Santa Barbara, but my favorite is a place where I hung out in college. It’s not fancy. It has steaks, onion rings, salsa, French fries. It’s called Joe’s Cafe,’” Khachigian remembers.

“He said, ‘That sounds perfect. Let’s go there.’ He loved it. Couldn’t have been happier. It reminded him of a steakhouse in Russell.”

Stu Spencer, the retired dean of California political consultants who was Ford’s national strategist in 1976, says Dole had “no match” for combining “a great politician, legislator and good-humored man. Throw in honesty and integrity and you wonder why he wasn’t elected president by acclimation.”

He never came close, losing California and the national electoral vote by large margins to President Clinton.

But Dole won the nation’s respect — and deserved it by acclimation.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.