Not all the unvaccinated are diehards, but the ‘wait and see’ crowd is shrinking

When Dr. Regina Chinsio-Kwong stopped by an Orange County vaccination site in late October, she asked people why they had waited so long to get their COVID-19 shots.

Some said they had not made the time, she said. One was nervous about needles, but had been prodded by an employer mandate.

“It’s not that they were against vaccines, but they just need that extra push,” said Chinsio-Kwong, a deputy health officer with the Orange County Health Care Agency.

Not all unvaccinated people have totally ruled out the shots. Some say they will “wait and see” about getting vaccinated, or will do so “only if required,” recent surveys from the Kaiser Family Foundation show.

But that group — those who are unvaccinated but still open to the idea — appears to be shrinking, the survey shows. Between March and October, the percentage who said they would either “wait and see” about the shots or get vaccinated only if it were required dropped from 24% to 9% of respondents.

During that time, the portion of people who said they will “definitely not” get vaccinated increased from 13% to 16%. The numbers suggest that as more people have been persuaded to get the shots, many of those who remain unvaccinated could be the most challenging for health officials to convince.

“It is increasingly a group that is dead set against getting the vaccine,” said Liz Hamel, vice president and director of public opinion and survey research for the Kaiser Family Foundation. Hamel said when the foundation previously tested different messages about vaccines, it had not found anything that swayed many people in the “definitely not” group.

Government officials and private companies have tried to step up pressure with new rules. In some areas, restaurants and other businesses are checking if customers are vaccinated before letting them inside. Hospitals, airlines and other employers have mandated shots for their workers.

Among those hospital workers is Authur Gorman, who got so sick from COVID-19 last year — before vaccines were available — that he had to use an oxygen tank at home for five weeks. He later urged friends: “If you have never had COVID, you should probably get the vaccine because you don’t want to be like I was in 2020.”

Gorman, a registered nurse at Mercy Medical Center in Redding, said he has given hundreds of shots at vaccination clinics. This summer, the Delta variant surge hit rural California so hard that the National Guard sent in medical teams to assist his hospital.

But when California ordered healthcare workers to get vaccinated, Gorman, 39, protested. He said he has not gotten inoculated because he has natural antibodies from getting infected.

“I’ve given hundreds of shots myself, but I’m labeled an anti-vaxxer,” Gorman said, calling the label a misnomer.

Gorman said that after getting COVID-19 twice, he gets his antibody levels checked regularly. He said if his antibodies wane too much, he would consider the vaccine. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has urged people who have gotten COVID-19 to get vaccinated, pointing to research indicating the vaccines offer better protection than natural immunity alone.) He said he had sought and been granted a religious exemption at his workplace.

As a nurse, “I’m exposed all the time, but I practice evidence-based medicine and take care of myself with PPE and state-of-the-art infection control measures,” Gorman said.

In the U.S., Republicans, white evangelicals and rural residents have remained less likely than other groups to report being vaccinated against COVID-19, according to KFF surveys in October. So have uninsured people under age 65, although they are more likely to be in the “wait and see” category than other groups with low rates of vaccination.

Vaccination rates also lagged earlier this year among Black and Latino people, but racial and ethnic gaps in vaccination appear to have narrowed in recent months while the political gap has persisted. The surveys found that 90% of Democrats reported they had gotten at least one dose of a COVID vaccine, compared with 61% of Republicans.

Even before the COVID-19 vaccine was available, the political divide was widening in the U.S., with Republicans becoming more opposed to vaccines between March and August of last year, while attitudes among Democrats changed little, an analysis by UC San Diego researchers found.

Democrats and Republicans also had diverging perceptions of the threat posed by the virus, which researchers suggested could be tied to the different media they consume.

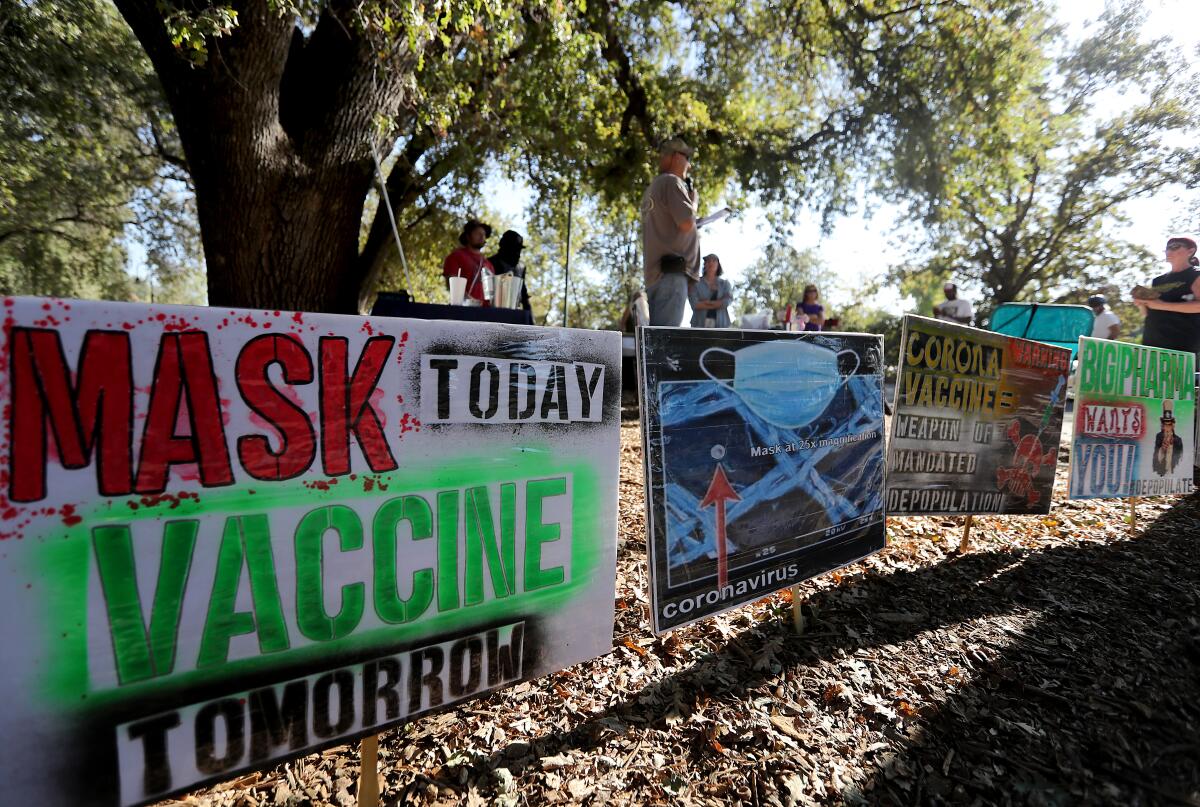

Vaccine hesitancy has also been tied to misinformation about the shots and their effects, researchers have found — and merely relaying information about them being safe and effective may not be enough to counteract it. In one study out of Poland, researchers found that none of the popular messages they tried were effective in reducing that hesitancy.

And distrust in government is tied to vaccine skepticism in general, which suggests that in many places, “governments may not be the most effective messenger for health advice,” said UCLA Fielding School of Public Health professor Corrina Moucheraud.

In Siskiyou County, Josh and JenniferJoy Cox said they are not vaccinated because of concerns about side effects, including myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart. The couple said they and their children have Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a rare connective tissue disorder that can weaken the aorta.

JenniferJoy Cox said she and her husband “absolutely believe that COVID-19 is a serious illness” and have lost four relatives to the virus. “We are not anti-COVID vaccination,” she said, “But for our particular family, we believe the risks are more than the benefits.”

In October, they joined more than 400 people who protested Gov. Newsom’s vaccination mandate for schoolchildren outside the Siskiyou County Public Health Department in Yreka, along with their four children. The Coxes are willing to homeschool to avoid vaccination.

But if their children eventually decide they want the shot, they added, they will let them.

In rural, conservative Northern California, distrust of the government runs deep, and residents have long wanted to secede to form their own state, called Jefferson.

Government mandates around health decisions have not played well there, the Coxes said. The number of daily new cases peaked in Siskiyou County during the summer surge, but the couple, who are medically retired Army veterans, said their small town of Fort Jones is so remote that they naturally enjoy social distancing.

“We live out in the middle of nowhere,” said Josh Cox, 39, a mechanic who served in Afghanistan and now cares for their children. “If Farmer Bob is at his chicken coop at 4 in the afternoon, I just stay away from the chicken coop. The risk from the vaccination is higher than the chance it works for me.”

“It’s a conservative area,” added JenniferJoy Cox, 36, who was a stateside military medic and now works at a rural community resource center. “Freedom and rights are very important to us. We both swore an oath to defend the Constitution, and we believe the mandates violate the Constitution and call that oath into play.”

The Ehlers-Danlos Society has advised that “for the majority of our community ... the benefits of protection against the COVID-19 virus are likely to outweigh the risks” of infection or vaccine side effects, but that those with a history of allergies to medications or severe reactions to injections should consult their doctor.

Among people who got vaccinated between June and September, many did so because they were concerned about surging cases and packed hospitals, according to KFF surveys. Others were moved by the illness or death of someone they knew.

And some were pushed to get the shots because of vaccination requirements to go to gyms or concerts, employer mandates, or pressure from family and friends, surveys found.

Dr. Jeanne Ann Noble, director of COVID response for the UCSF Emergency Department, said that people who aren’t motivated to get vaccinated by health concerns need to see “a very immediate, tangible benefit” to getting the shots, such as being able to go to sports arenas or possibly being freed from mask requirements. Employer mandates are also “an important part of that.”

At a vaccination clinic in August on L.A.’s skid row, Jasmine Daughtry said she was getting her COVID shot because it was required by casting agencies for possible gigs.

“I wasn’t going to get vaccinated, but my career comes first,” she said before getting her shot. Not being vaccinated “stopped me from working and making money. So now I’m ready.”

Hernan Hernandez, executive director of the California Farmworker Foundation, argued that mandates are needed, pointing to surveys showing that many farmworkers would get vaccinated if required for work.

“We’re dealing with a bloc that we are not going to change through education,” Hernandez said. “This is a bloc that continues to say ‘No,’ and we have to find a way to move beyond this pandemic.”

Mandates are polarizing, especially along partisan lines, KFF surveys have found. In Los Angeles, critics are calling for an initiative to overturn a soon-to-be-implemented city ordinance requiring customers to show they are vaccinated before heading into restaurants, movie theaters and other indoor venues.

Those rules represent “the government saying that they own your body and that they can decide that, ‘OK, you can only do certain things depending on what we say happens with your body,’” said Dan Welby, a regional representative for the San Fernando Valley area for the Libertarian Party of Los Angeles County.

Among unvaccinated workers, only 17% said they would likely get the vaccine if their employer required it without offering testing as an alternative, according to the KFF surveys. The majority — 72% — said they would leave their jobs.

Still, the KFF surveys found that only 5% of unvaccinated adults had actually left a job because of vaccination requirements. United Airlines, for instance, announced in September that more than 99% of its workforce had either gotten vaccinated or sought exemptions to its requirement.

Gorman, the Redding nurse, said he filed for a religious exemption from the COVID-19 vaccination, writing that he was a Christian for whom the shot is the Biblical equivalent of “unclean food” and “analogous to what non-kosher food is to orthodox Jews, and no one requires anyone in the United States to consume a substance contrary to their faith.”

He does, however, get an annual flu shot. He said he began doing so a few years ago because of a Shasta County mandate: Without that vaccine, he would have been required to wear a mask at work during flu season.

Times staff writers Rong-Gong Lin II and Lucas Money contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.