In California’s rural, conservative north, there are big dreams for cleaving the state

The two young, blond women in figure-flattering ball gowns hoisted whiskey and shotguns.

An auctioneer rattled off bids. Above the stage in the banquet hall hung a green flag for the 51st state of Jefferson, with its pair of Xs called a “double-cross” representing a sense of rural abandonment.

Hundreds of people packed into the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 9650 hall on this chilly Saturday night, ready to crack open wallets to help fund their dream of carving — out of California’s northernmost reaches — a brand new state.

Someone offered $350 for a state of Jefferson belt buckle. Someone else won a lamb, still in its mother’s womb, that should be born in time to be butchered for Easter. Outside, vehicles bore bumper stickers supporting President Trump and the 2nd Amendment.

“We Okies are fun, aren’t we?” one man quipped.

The scene last month in this small Shasta County city seemed like a perfect we’re-not-in-California-anymore-moment. That is, if you only knew California as the diverse, liberal bastion whose elected officials have tried to stymie the Trump administration’s moves on immigration, legalized marijuana, climate change and so on.

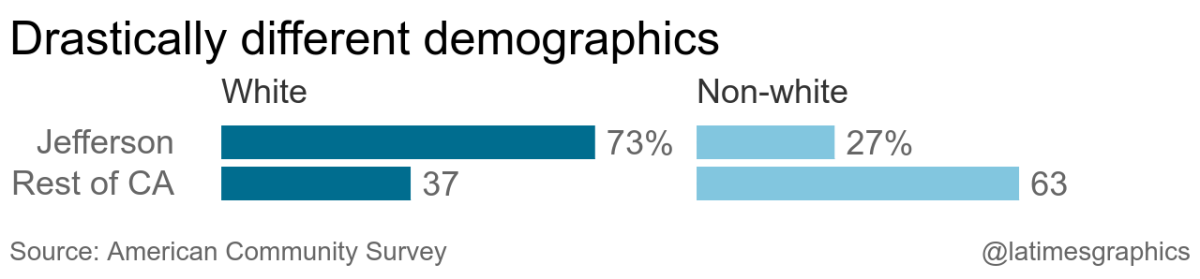

But the so-called Northstate is looking less and less like the rest of the Golden State. The vast, sparsely-populated region is whiter, more rural and poorer than the rest of the state — and residents are more conservative. While California has become the center of the resistance to Trump, a number of Northern Californians are waging a resistance of their own: against California itself.

Inside the banquet hall, the man many see as the founder of the modern Jefferson movement told the crowd that their gun rights, property rights, grazing rights and water rights were under siege by politicians who write them off as “country bumpkins.”

“You’re the ones being exterminated by a lack of liberty,” said Mark Baird, a Siskiyou County rancher.

The breakaway state of Jefferson is a decades-old idea, but it has been revived in earnest in recent years by residents who say they are fed up with their voices being drowned out in Sacramento, where outspoken urban Democrats hold a vise grip on the state Legislature.

Supporters say overregulation has hobbled rural industries such as timber, mining and fishing and that the state’s high taxes and cost of living are driving young people away, quickening the decline of small towns. They chafe under California’s strict gun-control policies and are infuriated by its liberal immigration laws.

They cite California’s new gas tax increase of 12 cents per gallon, saying it has an outsize impact on rural people who drive farther for work and basic needs such as hospitals, schools and grocery stores.

How likely is it that a new state will be broken off, like a piece of Kit Kat bar, from California? Not likely at all, experts say.

Eric McGhee, a political scientist at the Public Policy Institute of California, said that while you can “never say never,” there are too many legal obstacles to overcome.

“It’s easy to think that because there’s this large piece of territory, that it’s a large share of California in terms of the population," he said. “That’s just not the case. … It’s an absolutely minuscule portion of the state’s population.”

Supporters of a breakaway state say they are sorely underestimated and point to the number of passionate people who show up to their events. One man put it this way: “We’re not a bunch of dumb rednecks.”

When we first started ... people would say, ‘What’s Jefferson? ... Now, they’re saying, ‘When are you going to get this done?

— Janet Chandler

But some Northern Californians have had enough of talk of breaking away from California. After several county boards began considering Jefferson proposals, Kevin Hendrick, a retired municipal employee from Crescent City, in Del Norte County, formed a political action committee in 2015 called Keep It California to oppose the idea.

“You’ve got a handful of residents that are grumpy and pining for the good old days, but that shouldn’t represent all the good people living in rural counties,” he said.

Hendrick said there are rural issues that do need more attention, such as access to affordable healthcare and the internet, but that separating from California would be financially devastating.

“People need hope, yes,” he said. “They don’t need false hope.”

There has been plenty of talk recently about cleaving California. There was the failed 2014 effort to split the state into six states. There’s a plan to form New California, which includes everything but a sliver of wealthy, urban coastal counties. And there’s Calexit, the movement for the state to secede from the Union entirely, an idea that gained steam after Trump’s election.

Jefferson, which has included some Oregon counties in various iterations, precedes them. In one of the movement’s most colorful eras, armed separatists in November 1941 set up roadblocks along Highway 99 in Siskiyou County. But the movement was halted days later when Pearl Harbor was bombed.

The modern Jefferson movement was kicked off in 2013 when boards of supervisors in Siskiyou and Modoc counties passed declarations of support for withdrawing from California.

Win Carpenter, a Jefferson organizer from Redding, said declarations from 21 counties have been filed with state officials. Some are proclamations by county boards of supervisors; others are collections of signatures by residents.

Carpenter, 55, a seventh-generation Shasta County resident, quit his job as an appraiser in the county assessor’s office in 2015 to devote his time to Jefferson. Days later, he told the Shasta County Board of Supervisors that, although the board had declined to support the breakaway state, advocates had gathered thousands of signatures anyway.

“As your employers, we have decided you will not be representing us on this issue,” he told the supervisors. “Therefore, we are moving ahead without you.”

If Jefferson became a state, it would have 1.7 million residents, a population bigger than 13 other states. It would be 73% white. Present-day California has roughly the same number of whites and Latinos, at about 14.8 million each.

Jefferson supporters have their hopes set on a federal lawsuit. Last year, a group called Citizens for Fair Representation — including Carpenter, Baird and other Jefferson proponents along with a Native American tribe, the California Libertarian Party and the city of Fort Jones, Calif. — sued the state, alleging an unconstitutional lack of representation and dilution of vote.

California’s 120 state legislators, the suit states, cannot adequately represent 40 million residents. In Northern California, one senator represents nine counties and parts of two more. The idea, Baird said, is for California to either be forced to add thousands more legislators or that the state would refuse and let Jefferson leave.

Baird had just finished an impassioned speech about Jefferson in Placerville last month when Riley Taresh, 19, stepped up to the microphone, her voice solemn.

“How much longer do we have to wait?” she asked. “I only have a few more years where I can go to school here before I have to leave because I won’t be able to afford to stay in California.”

Taresh, of Shingle Springs, works part time at Payless ShoeSource while attending Folsom Lake College. She can’t afford to move out of her parents’ home. She wants to work in the medical field and stay in Northern California, but “as a working-class poor, it is not possible for me,” she said. She believes her chances at getting into a four-year state university were hindered, in part, because she is white.

“I’m like, excuse me, I have to work my butt off to get anywhere, and you’re going to hand illegals … a driver’s license, you’re going to hand them an education, and I have to work my butt off until I’m in tears and begging for help to get anywhere. No.”

Mike Murray, 32, of Rocklin, said he hates “the perception that it is these old white people that just want to go around and spit their tobacky and shoot their guns.”

Murray has been trying to attract younger, more diverse people. He sees Jefferson as a “reset button.” An uncle of his packed up his business and moved to Texas because of high taxes. His in-laws are frustrated by California’s strict gun laws, which, he said, aren’t feasible for them since they are rural farmers who would have to wait a half-hour for police if someone broke in.

I just like the whole idea of getting back to the Constitution, getting back to the principles that made this country great in the first place.

— Sally Rapoza

Just after 7 a.m. on a recent Friday, Terry Rapoza stood before the Sunrise Rotary Club at a Redding Best Western explaining the case for Jefferson while his wife, Sally, handed out pamphlets.

A stout, mustachioed man with a booming belly-laugh, Rapoza said there was “no rule of law in the state of California.” He recently called a White House hotline to say Gov. Jerry Brown had repeatedly violated the Constitution.

A gregarious couple in their 60s, the Rapozas, of Redding, helped start a local tea party group shortly after President Obama took office. A 2009 tea party protest at Redding’s Sundial Bridge drew some 2,000 people, and their son, Clayton, a labor organizer and Civil War reenactor, dressed as a Revolutionary War minuteman and led protesters across the walkway.

“I just like the whole idea of getting back to the Constitution, getting back to the principles that made this country great in the first place,” Sally Rapoza said of Jefferson.

For the Rapozas, California’s sanctuary policies are emblematic of the unchecked power of the state Democratic party. They were thrilled when the Shasta County Board of Supervisors approved a non-sanctuary resolution last month.

“Why are we allowing illegal aliens to come into our country?” Sally said. “I mean, that’s an invasion. … It feels like our rights are being diminished and their rights are being exploited, actually, because the Democrats want votes and the Republicans want cheap workers.”

Sally, whose organizing skills earned her the moniker Rally Sally, uses her Facebook page to live-stream events and drum up Jefferson support. The official State of Jefferson website lists her as a social media organizer. She also shares political posts on her page, including Breitbart articles and a meme calling Hillary Clinton “the Russian spy who hacked our primaries.”

Terry co-hosts a weekly AM radio show, “Jefferson State of Mine,” with Carpenter. It opens with a country song about Jefferson: It’s a wave on a dusty road. It’s a logger’s heavy load. It’s the cattle on the hills. It’s the ridge full of thrills.

In the small mountain town of Burney, Harold and Janet Chandler live on a quiet street among the pine trees. They have a Jefferson sign in their yard and Jefferson coffee mugs in their cupboards.

The couple — she a retired school teacher, he a retired California Highway Patrol officer — moved to Burney in 1991, when it was a bustling logging town with two clothing stores, two shoe stores, two grocery stores, they said. But the timber mills cut back. The families left. Now, shuttered storefronts line Main Street.

Janet, who unsuccessfully ran for county supervisor in 2016 and openly supported Jefferson, said regulations would be eased in the new state, bringing back jobs — and hope. She and Harold are on a committee that recently finished writing a 29-page Jefferson constitution.

“When we first started handing out brochures and carrying signs at parades, people would say, ‘What’s Jefferson?’” Janet said. “Then, the phrase became, ‘Oh, it’s a good idea, but it’s never going to happen.’ Now, they’re saying, ‘When are you going to get this done?’”

Twitter: @haileybranson

Los Angeles Times staff writer Ryan Menezes contributed to this report.

Dig deeper into the area’s demographics in The Times’ Jefferson census

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.