Coastal erosion in San Clemente threatens railroad tracks, pricey homes

Each day after the tide went out, workers piled enormous rocks onto the sandy beach.

They were rushing to dump at least 11,000 tons to keep the ocean at bay and reopen a picturesque stretch of railroad track in San Clemente.

In the nearby Cyprus Shores gated community, cracks recently began surfacing in the clubhouse and several multimillion-dollar homes. The tracks were shut down last month after large waves swept in and the ground became unstable.

The forces at work along this beach and the rest of the California coast cannot, in the long run, be stopped by a stack of boulders. Climate change has led to rising sea levels, which translates to more intense battering of beachside communities.

What’s more, decades of development have paved over sand and soil that would help block the encroaching waves.

In San Clemente, long-term solutions could involve relocating the railroad tracks or restoring sediment that would help create natural barriers. For now, the tracks, which carry Metrolink commuters and Amtrak travelers up and down the coast, are scheduled to reopen Monday with the rocks as protection.

After decades of development that destroyed countless acres of coastal marsh, Southern California’s environmental “bank account” is empty, said Brett Sanders, professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Irvine.

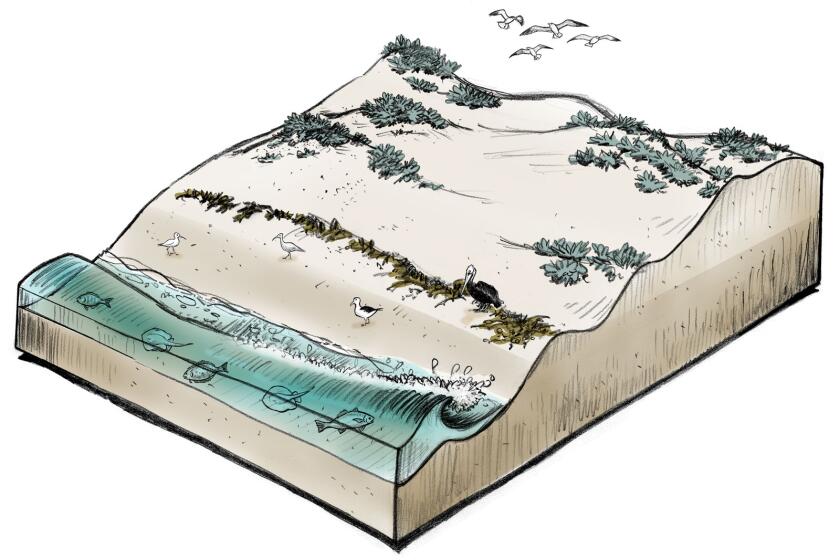

As sea levels rise, researchers are trying to bring back beach dunes and help buy communities a bit more time — before the ocean pushes inland and reclaims the land.

The building of marinas and harbors in the 1930s to the 60s, including nearby Dana Point Harbor, released large amounts of sand, widening the beaches. It’s the blocking of sand supply by dams, debris basins and seawalls that prevent natural replenishment of the beaches, said Richard Behl, a marine sedimentologist and geology professor at Cal State Long Beach.

“You can’t just keep taking from the beaches without nursing them, giving the nourishment they need,” Sanders said.

Building the rock barrier, known as riprap, was an “exhausting project,” since the raw material could be unloaded only during low tide, said Metrolink spokesman Paul Gonzales.

“We’re doing what we can working between the sea, the sand and earth, and we understand everyone’s waiting to ride again,” he said.

Hard barriers like riprap or sea walls do not block sand transport, but do boost the reflected energy of waves, making them more

erosive and leading to the removal of beach sand and narrowing of beaches at a particular location, Behl said.

For Sanders, San Clemente is an ideal place for a project that rebuilds beaches and ultimately protects the railroad track and houses. But it will take quick action from regional leaders, he said.

Stefanie Sekich-Quinn, coastal preservation manager for the environmental group Surfrider Foundation, also called on government leaders to focus on long-term planning, especially in light of climate change and sea level rise.

In Del Mar, a series of erosion catastrophes finally led to a long-term solution, supported by local members of Congress, to move the tracks inland, Sekich-Quinn said.

“In hindsight, we are in this predicament because people have built too close to the coast in the past, and in order to solve this problem, we need to look to the future,” she said.

At Gleason Beach, a major highway realignment shows the complicated realities of dealing with climate change on the California coast.

The bluffs in the Cyprus Shores community, where four homes are under immediate threat, have long been stabilized by the beach below, said Lesley Ewing, senior engineer for the Coastal Commission. Some stretches of beach enjoyed by swimmers and sunbathers may have to give way to coastal protection habitat if the area is to be saved, she said.

San Clemente Councilman Gene James has seen the waves creep closer since he moved to the city five years ago.

“The ocean’s coming right up to the railroad tracks and yes, there’s an urgent need to mitigate, and there’s a need to maintain our tourist base while taking care of residents,” he said.

James said he is “very concerned” but did not elaborate on possible solutions.

Amy Gutierrez walks her pointer mix, Pepper, along the beach near Cyprus Shores and takes the train to her bookkeeping job in Oceanside. Since the tracks shut down in mid-September, she has been working from home.

“We cannot — must not — let the ground open up under us,” she said. “We need to rely on the best minds to solve the equation of erosion. We must get back to normal.”

While in town to visit her family, Beth Jones runs past Cyprus Shores and the railroad tracks every morning. She and her boyfriend, Timmy Weiss, live in New York City. The beachside vacation is a needed respite from urban life.

Jones said she does not have an answer for how to stop the beach from washing away.

But she cannot envision coming back to Orange County to “witness less and less of the coast” each time.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.