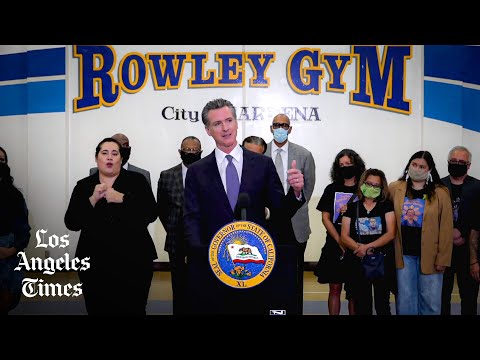

Gov. Newsom approves sweeping reforms to law enforcement in California

The changes include raising the minimum age for officers to 21 and allowing badges to be taken away for excessive force, dishonesty and racial bias.

SACRAMENTO — More than a year after George Floyd’s death, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a stack of bills on Thursday aimed at holding California law enforcement officers accountable for misconduct and restricting uses of force that have resulted in death and injury.

The eight measures signed into law by Newsom include raising the minimum age for police officers from 18 to 21, and allowing their badges to be permanently taken away for excessive force, dishonesty and racial bias.

In addition, the new laws set statewide standards on law enforcement’s use of rubber bullets and tear gas for crowd control, and further restrict the use of techniques for restraining suspects in ways that can interfere with breathing.

Newsom’s approval of the slate of sweeping new legislation in California comes in contrast to a lack of progress made on police reform efforts in Congress, where bipartisan negotiations on law enforcement accountability measures recently reached an impasse after months of negotiations.

The impasse marks the collapse of an effort that began after the killings of unarmed Black people by officers sparked protests across the country.

“I want folks not to lose hope, that just because things aren’t happening in Washington, D.C., that we can’t move the needle here, not just in our state but in states all across this country,” Newsom said at an emotional signing ceremony Thursday at Rowley Gym in Gardena.

He recognized that some communities are on edge over police abuse and the lack of national reform. “I hope this provides a little contrast to that anxiety and fear,” he said of the package of new laws.

The governor was joined at the ceremony by several legislators and state Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta, as well as the tearful family members of people who have died at the hands of police.

Law enforcement groups opposed some of the state measures, warning that they will undermine the ability of officers to keep Californians safe from criminals. But a group of progressive prosecutors, including Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, supported changes that they believe will address unfairness in the law, especially for people of color.

“The California Legislature took significant steps towards addressing deep injustices in our criminal legal system,” said Cristine Soto DeBerry, executive director of Prosecutors Alliance of California, the group of progressive district attorneys. “These bills will help take problematic police off the streets.”

Lawmakers were responding to concerns over incidents such as the May 2020 killing of Floyd that occurred when a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for more than nine minutes during an arrest.

The death led to international protests calling for police accountability and the conviction of a police officer for murder.

“We are in a crisis of trust when it comes to law enforcement right now,” Bonta said, adding that the new laws will provide “more trust, more transparency and more accountability.”

The ceremony was held at a park where Kenneth Ross Jr. was shot and killed by a police officer three years ago. State Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) cited the loss of lives at the hands of “rogue policing.” The bills signed by the governor include a measure by Bradford that allows the lifetime decertification of law enforcement officers found to have engaged in misconduct.

The bill gives new powers to the state’s 17-member Commission on Peace Officers Standards and Training to suspend or revoke officers’ certification.

Bradford said the bill was needed because police officers who are fired or resign because of misconduct sometimes go to work for other law enforcement agencies.

Senate Bill 2 “establishes a fair and balanced way to hold officers who break the public trust accountable for their actions and not simply move to a new department,” Bradford said.

California joins 46 other states that have procedures to block abusive officers from transferring jobs.

Bradford’s bill allows the state’s 17-member Commission on Peace Officers Standards and Training to investigate and suspend or revoke the certification of peace officers based on the recommendation of an advisory panel made up largely of citizens appointed by the governor.

More than three dozen groups representing police officers, including the California Police Chiefs Assn., opposed the bill, saying the measure subjects officers to double jeopardy with overly broad definitions for what constitutes wrongdoing and involves a potentially biased panel without expertise in law enforcement.

“SB 2 merely requires that the individual officer ‘engaged’ in serious misconduct — not that they were found guilty, terminated, or even disciplined,” the chiefs said in a letter to lawmakers.

The governor also signed Assembly Bill 89, which raises the minimum age for police officer recruits from 18 to 21 and calls for state colleges to provide a modern policing degree program for new officers by 2025. Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles) said Thursday that his legislation is “relying on decades of data showcasing that more mature and better-educated officers are less reliant on excessive force.”

He said the higher education program being developed will equip officers with skills to de-escalate situations, “while also ensuring they develop a critical understanding of the history of communities of various backgrounds.”

The legislation was opposed by the Peace Officers’ Research Assn. of California, which represents 77,000 public safety officers in the state and said any new standards should be phased in and “mindful of disadvantaged individuals who desire a career in law enforcement.”

Newsom also said he is signing AB 48, a measure that addresses complaints during the last year of demonstrations over police force cases, including the Floyd killing. Activists said they were injured when police improperly fired rubber bullets at crowds of peaceful demonstrators.

Five decades of evidence show that rubber bullets can maim, blind and even kill people, but they still are being used widely by police to quell protests and unrest.

The bill by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego) sets statewide standards on law enforcement’s use of rubber bullets and tear gas for crowd control. The legislation requires law enforcement officers to be trained on the safe use of kinetic projectiles and chemical agents and other de-escalation techniques before using projectile weapons.

The bill also bars aiming those weapons at the head, neck or other vital organs.

“During the nationwide protests in 2020, many reports showed peaceful protesters and bystanders being seriously injured, even permanently maimed, by dangerous projectiles,” Gonzalez said. “This bill will protect Californians’ right to safely protest by establishing statewide standards that help minimize the overuse of these dangerous weapons.”

The governor also acted to expand last year’s law banning the use of chokeholds by law enforcement.

AB 490 prohibits law enforcement agencies from authorizing restraint techniques and transport methods that involve a substantial risk of positional asphyxia — situating a person in a manner that compresses the airway and reduces the ability to sustain adequate breathing.

Assemblyman Mike Gipson (D-Carson) said his bill addresses cases in which officers seeking to restrain civilians have knelt on the neck in a way that prevents them from breathing.

The governor also signed AB 26, which requires law enforcement agencies to adopt stricter policies mandating that officers intercede when they see a colleague using excessive force and immediately report the incident.

The measure provides that an officer who receives training in use-of-force practices and fails to intercede could be disciplined up to and including the same penalty as the officer who committed the excessive force.

Assemblyman Chris Holden (D-Pasadena) said he introduced the legislation after the killing of Floyd was witnessed by other officers who failed to intervene.

“While the public was outraged by the supervising officer’s disregard for Floyd’s life, what was equally troubling was that the other three officers failed to stop the supervising officer, despite Minnesota’s Duty to Intervene law,” Holden said.

The measure was opposed by the California Assn. of Highway Patrolmen, which said it was involved two years ago in a working group that negotiated changes in use-of-force policies that require intervention.

The association said in a letter to lawmakers that officers who arrive late to the scene of an arrest and see officers wrestling with a suspect on the ground may not have enough information about what transpired to know whether to intercede.

“The arriving officer may not know that the suspect has a weapon, or has potentially used, or attempted to use, that weapon on the officers prior to their arrival on the scene,” the highway patrol group said. “Without the arriving officer having full knowledge of the situation, that officer’s intercedence could be dangerous to both the officers and the public.”

Other new laws approved by Newsom expand the types of police officer personnel records subject to public disclosure to include those involving sustained charges of excessive force and improper arrests, and seek more transparency for law enforcement agencies that acquire military equipment, including a mandate to adopt a public policy.

The governor also signed into law a requirement that police agencies adopt policies that prohibit officers from participating in law enforcement “gangs,” that critics have said use violent and intimidating tactics similar to those employed by criminal street gangs.

A new study finds that 16% of L.A. County Sheriff’s deputies and supervisors said in an anonymous survey they’ve been asked to join a secret clique.

AB 958 by Assemblyman Gipson is supported by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, which has faced criticism over allegations that gang-like cliques of deputies exist in its ranks, even though the agency has a policy against such activity.

“These are groups who celebrate excessive force, resist reforms and discriminate against other officers,” Gipson said. “How can we expect an officer to uphold the public safety of our communities when that officer is pressured within their own department to join a police gang?”

The torrent of criminal justice bills this year signaled that state elected leaders were listening to public concerns, according to DeBerry, the head of the prosecutors alliance.

“The Legislature’s actions reflect the will of the voters of California who have made clear over and over that they support reforms that promote racial justice and fairness,” DeBerry said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.