U.S. lawmakers end bipartisan police overhaul talks with no deal

WASHINGTON — Bipartisan congressional talks on overhauling policing practices have ended without an agreement, top bargainers from both parties said Wednesday, marking the collapse of an effort that began after the killings of unarmed Black people by officers sparked protests across the United States.

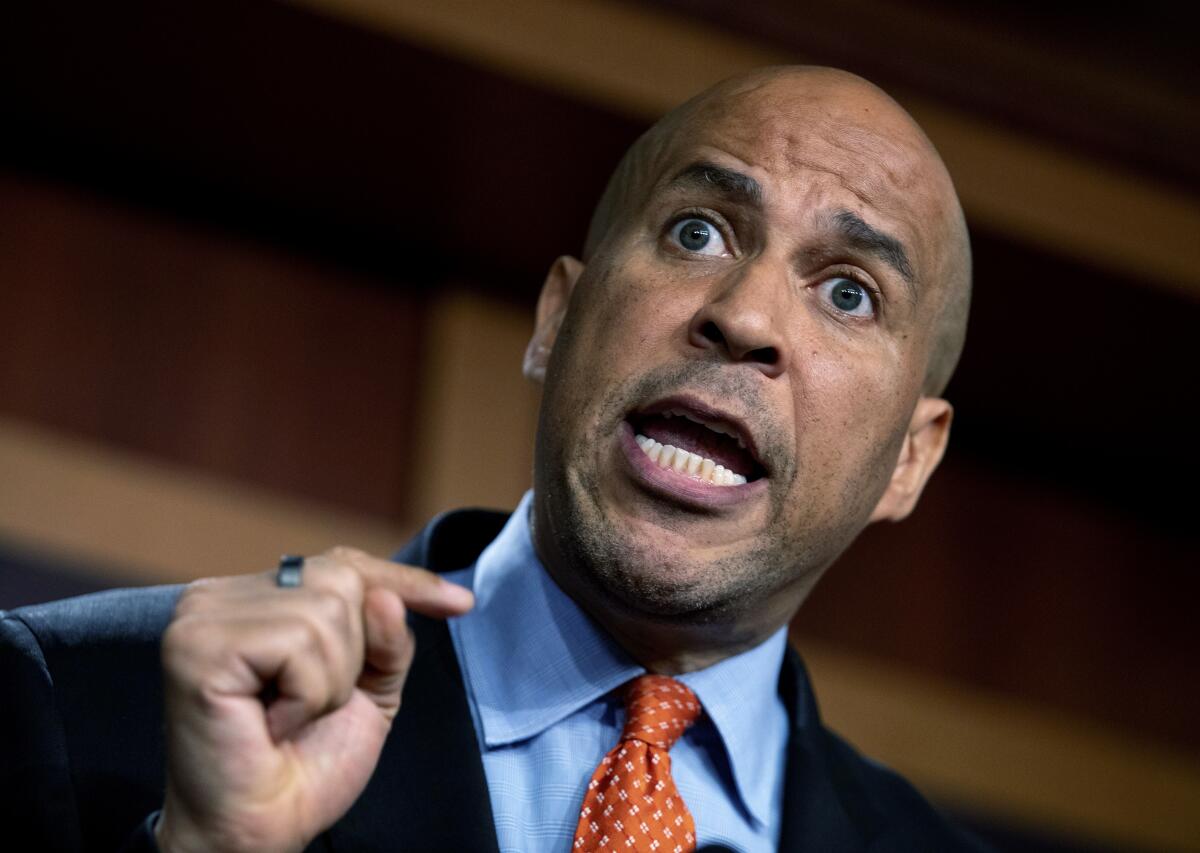

“It was clear that we were not making the progress that we needed to make,” Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) told reporters. He cited continued disagreements over Democrats’ efforts to make officers personally liable for abuses, raising professional standards and collecting national data on police agencies’ use of force.

Booker said he’d told South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, the lead Republican negotiator, of his decision earlier Wednesday. Talks had moved slowly for months, and it had became clear over the summer that the chances for a breakthrough were all but hopeless.

Repeated visits to Washington by victims’ relatives helped keep pressure on the issue. But in the end, Booker said, “I couldn’t get to a point where I can meet with families and tell them that we were going to address the specific issues that were putting your family member in harm’s way.”

Scott said he was “deeply disappointed” that Democrats had walked away from accords reached on several issues, including banning chokeholds, curbing the transfer of military equipment to police and increased funds for mental health programs, which address problems that often lead to encounters with law enforcement officers.

“Crime will continue to increase while safety decreases, and more officers are going to walk away from the force because my negotiating partners walked away from the table,” Scott said in a statement.

Democrats rejected a deal “because they could not let go of their push to defund our law enforcement,” said Scott, using a catchphrase of progressives from which most Democrats in Congress have disassociated themselves. “Once again, the left let their misguided idea of perfect be the enemy of good, impactful legislation.”

The failed congressional effort followed high-profile police killings last year of Black people, including George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky. Those killings and protest demonstrations in scores of cities that followed called attention to abusive police behavior and the disproportionately high number of Black people who are victims of fatal encounters with law enforcement.

In a statement Wednesday, President Biden called Floyd’s killing “a stain on the soul of America,” adding, “We will be remembered for how we responded to the call.”

He said Senate Republicans had “rejected enacting modest reforms” that then-President Trump had backed and that some law enforcement organizations were open to. He cited new Justice Department policies on chokeholds and other practices, and said his administration would seek ways, including with executive orders, “to live up to the American ideal of equal justice under law.”

Booker cited support that parts of the effort had won from police organizations and said he was talking to the White House, other congressional Democrats and civil rights and other outside groups about still making some progress on the issue. But he avoided specifics.

“I just want to make it clear that this is not an end,” he said.

Attorneys Ben Crump and Antonio Romanucci, who have represented shooting victims’ families, expressed “extreme disappointment” in the talks’ failure to reach “a reasonable solution” on the issue.

“We cannot let this be a tragic, lost opportunity to regain trust between citizens and police,” they said. They said the Senate should vote anyway on Democrats’ policing bill — which Republicans would be certain to defeat with a filibuster, or procedural delays, but would let voters “see who is looking out for their communities’ best interests.”

One response to George Floyd’s death was rejection of police reform, which, opponents argued, only perpetuates a racist system. Still, reform is needed.

The police killings and the public reaction quickly caught the attention of both political parties, and work began in Congress to write legislation that would curb and monitor the police use of force. But from the beginning, some from each party voiced suspicions that their rivals would make few concessions in hopes of retaining an issue — crime for Republicans, restraining police for Democrats — that they could use to appeal to voters in election campaigns.

Political roadblocks soon emerged. Democrats blocked a Republican Senate bill last year that they said was too weak, while a tougher House-approved bill this year was derailed in the Senate by the GOP.

Lobbying trips to Washington by victims’ families and Biden’s call this spring for a bipartisan deal by May 25, the anniversary of Floyd’s death, seemed to provide momentum for the effort. But May 25 came and went without an agreement.

Booker and Scott, among only three Black senators, refrained from criticizing each other throughout the talks and held to that on Wednesday. The two have said they are friends and have cited similar experiences of being challenged by officers.

“We disagree on a lot of issues, and in this case, I’m disappointed that we have those disagreements,” Booker said. “But we both share the humiliation of being stopped by police officers.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.