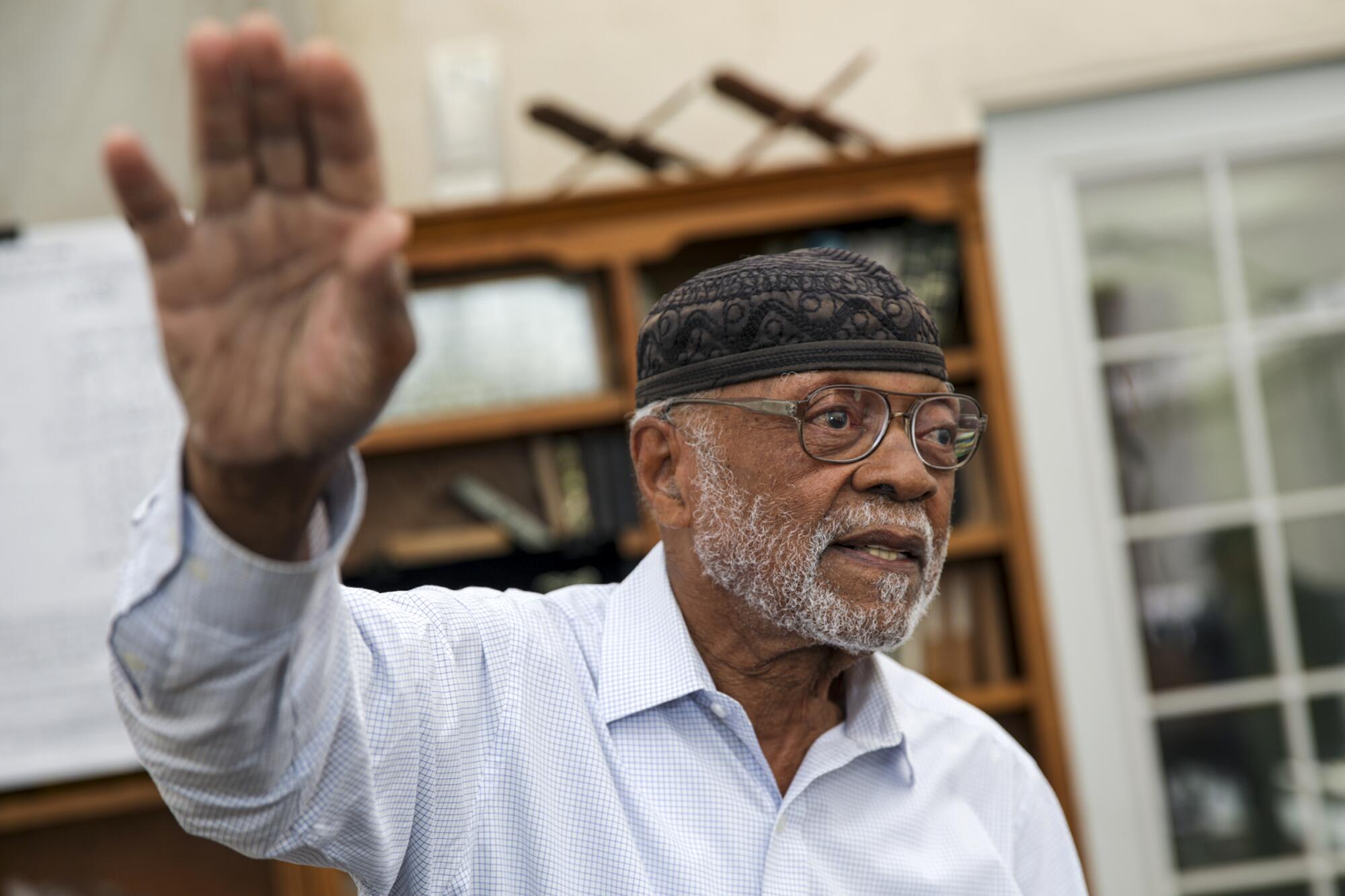

Beneath the glinting green dome of a mosque off Malcolm X Way in South Los Angeles, a spiritual leader in his late 80s is hammering home a vital message: African American Muslims must be engaged in their community and not let others make decisions for them.

Imam Abdul Karim Hasan embraced Islam more than 60 years ago after hearing Malcolm X. He recalls listening, mesmerized, as the fiery Muslim minister and civil rights leader recounted the history of slavery in America — and that many of the Black captives were Muslim.

The inspiration that Hasan drew from that wintry night in Connecticut still shapes his conviction that African American Muslims must dive into the politics that shape their lives.

“Malcolm was my teacher,” says Hasan, 89, the slender leader of Masjid Bilal Islamic Center. The mosque founded a half-century ago is a place for spirituality, Hasan says, but worshippers must live in America — not the masjid.

“Why are you sitting back and letting other people make the rules, and you don’t attend a council meeting to see what they’re doing or saying?” Hasan asks. “You’re not going to change anything sitting in your living room.”

About five miles away, in a boxy tan building across the street from a barbershop called the Shave Parlor, stands another masjid and community center, Islah LA. Founded in 2013, it is led by Imam Jihad Saafir, who is 49 years younger than Hasan.

Together, the mosques and their imams represent the challenges — demographic, economic, political — as well as the potential of African American Muslims, a faith community that often receives less attention than immigrant Muslims, but whose U.S. roots stretch back centuries.

Hasan’s decades of service are memorialized on a sign at the intersection of Central Avenue and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard: “Imam Hasan Square.” Saafir hopes to expand on the legacy of Hasan and other elders while drawing in a youthful generation seeking spiritual sustenance and political guidance.

“We are products of their stories. We’re younger, we want to move a little faster, we want to take a few more chances,” Saafir says. “Imam Hasan, alhamdulillah, he is an elder to me. He is a very important part of, shoot, even why I’m here.”

For Saafir, that means revering the past while providing services that help South L.A. today. “You can invoke Malcolm all you want, talk about him and his speeches,” Saafir continues. “But these are some Malcolms here that you need to invest in.”

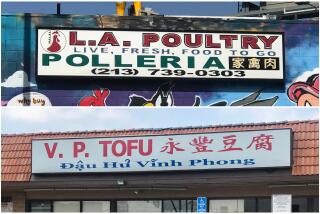

African American Muslims represent nearly one-third of Muslims in the U.S., data show, and about 15% of mosque attendees in Southern California. Though many congregants at the handful of mosques in South L.A. are Black, worshippers of various ethnicities fill their halls.

“The only thing that can separate us is fear and ignorance,” Hasan says. “African American Muslims know there is a common bond between Muslims everywhere.”

African American mosques made up 13% of all U.S. mosques in 2020, according to the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. That’s a drop from 10 years ago, when they accounted for 23% of all masjids.

“The community is on the decline, so we have to put a robust effort towards keeping our youth and making sure that there are new Muslims also converted,” Saafir says.

Researchers cite various reasons for the decline: fewer Black converts to Islam, the inability of mosques to attract and retain young adults and the overall aging of African American Muslims, many of whom converted in the 1960s and 1970s.

Many of those converts were heeding not only a spiritual call, but the urgent voices of the civil rights and Black Power movements resisting racist oppression. In South LA, community leaders say, the priorities for many in the Muslim community still center on social justice, strengthening the family and obtaining economic parity.

“No. 1 for us is economics and being behind financially. Two is families — making them strong,” says Imam Rushdan Mujahid-Deen, associate imam at Bilal. “I feel the pain of Palestinians, and the Burmese [Rohingya], but that’s not the No. 1 issue for us. We support their cause and want to help free their people, but we have to help free our people too.”

::

Following prayers at Islah LA on a recent Friday afternoon, congregants embrace Saafir or shake his hand in gratitude for his sermon.

The imagery on the walls surrounding them is a reminder of what’s possible for the youth Saafir helps shepherd, both in ministry and through Islah’s school: laminated pennants from historically Black colleges and universities, an apple tree made of tissue paper, with students’ photos pasted on the hanging fruit.

A line beneath it reads, “They tried to bury us. They did not know we were seeds.”

Islah was born out of Masjid Ibaadillah — a community led by Saafir’s father, Imam Saadiq Saafir — on West Jefferson Boulevard that was established to serve its predominantly African American attendees. The Islah LA community center, a secular nonprofit charity, started “safe-place programming for children and families” in 2014, and opened its academy that fall, offering a curriculum specializing in social justice, Quranic studies and “21st century leadership.”

The center has about 150 members, Saafir says. Many who attend “have been injured by mass incarceration.”

“Some of them are now business owners. We have one of our brothers, he did over 10 years. And he was a gang member in this neighborhood. And now he has a trucking company.

“Islah is used as a word in the Quran,” Saafir adds. “It means to revive, renew, restore something, right. But it also means to restore relationships between people.”

The “dream of the inner city,” he says, is to couple a house of worship with a dynamic center that serves multiple kinds of congregants — including the younger set who have asked for more activities. To answer that call, Islah diversified its programming, with both the fun (paintball tournaments) and the inspirational (field trips to local businesses and the opportunity for youths to shadow store owners).

“They need to see the possibilities that they can end up fulfilling, to see their potential self,” Saafir says. “It’s meaningful experiences that they will never forget.”

“The community is on the decline, so we have to put a robust effort towards keeping our youth and making sure that there are new Muslims also converted.”

— Jihad Saafir, Imam at Islah LA

Kenyatta Bakeer, a member of Islah who helped launch its school, says the organization’s community work is born out of “a duty in our own space.”

“We need to look at what is happening right in our own backyard,” she says. “Whether they convert to Islam or not, our priority is being able to be a sanctuary in the middle of South Central.”

::

Although Islam had been practiced in the New World for centuries, a new permutation of African American Islam emerged in the 1930s, when a salesman named Wallace D. Fard founded the Nation of Islam in Detroit as a Black separatist movement with a doctrine that bears little resemblance to mainstream Islam.

In the socially turbulent decades bracketing World War II, other Black separatist, Black nationalist and Pan-African organizations arose, claiming various degrees of affinity with Islam.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, under the mentorship of Nation of Islam’s new leader, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X helped the organization raise its profile through messages like the one a young Imam Hasan heard, speeches that encouraged Black economic self-reliance, pride and self-determination.

American Islam made a broader cultural and political impact in the ‘60s, when Malcolm X embraced orthodox Islam, and heavyweight boxing champion Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964. A decade later, the Black Muslim community splintered when Imam Warith Deen Mohammed succeeded his father, Elijah, as leader of the Nation of Islam. Mohammed rejected the Nation’s more controversial beliefs and founded the Muslim American Society.

As increasing numbers of African and Middle Eastern Muslims immigrated to the United States in recent decades, the makeup of America’s Muslim communities changed yet again. A 2019 study by the Pew Research Center found that just 2 of every 100 Black Muslims surveyed identified with the Nation of Islam. Most U.S. Muslims who are Black either identify as Sunni — 52% — or with no particular denomination, the study said.

To Imam Hasan, the move to mainstream Islam under Warith Deen Mohammed represented “evolution” for the community.

“If we had the wrong concept of Islam, I wanted to get the right concept,” Hasan says. “I didn’t want to go on the same old path because I couldn’t learn anything from that.”

There were also those who chose not to follow Warith Deen Mohammed. Some broke away to follow the Nation of Islam’s new leader, Minister Louis Farrakhan, who preached Black pride in speeches he sometimes laced with antisemitic and homophobic comments.

The growing diversity of the U.S. Muslim population has altered societal perceptions of what it means to be Black and Muslim. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer, a Purdue University professor and author of “Muslim Cool: Race, Religion and Hip Hop in the United States,” said that there is a sense of erasure among many in the community because of “silence in popular discourse around Black Muslims.” In her book, Khabeer writes that her research challenges the “racialization of Muslims as foreign and as perpetual threats to the United States.”

“Mainstream media generally ignores Black Muslims, even though everyone loves Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali,” she says.

It’s a feeling that Saafir knows well. At times, Saafir says, to be Black and Muslim can feel like the “invisible man,” overlooked during conversations about Islam in the U.S. despite the Black community’s contributions to the faith.

“It’s the African Americans,” he says, “who put Islam in the spotlight.”

::

An enduring sense of duty to the community also permeates Masjid Bilal, which sprouted from a community first led by other ministers in Muhammad’s Temple of Islam #27 on Broadway more than 50 years ago. Imam Hasan took the reins in 1971, and the community purchased Bilal’s current property in 1973.

The building that once stood there was demolished in the 1980s due to earthquake damage, and the mosque has been expanding since 1999. The center finished building a charter school on its grounds in 2007. Most of the students are Latino, Hasan says, and the majority are not Muslim.

Bilal doesn’t keep count of how many people attend the mosque. Hasan’s flock skews older than Saafir’s, and worshippers trickle in from the neighborhood and beyond — some driving from as far as Bakersfield for Friday prayers.

“The only thing that can separate us is fear and ignorance. African American Muslims know there is a common bond between Muslims everywhere.”

— Imam Abdul-Karim Hasan

The masjid is raising funds to add a mixed-use building with businesses and low-income apartments. The new masjid and community center are still under construction, though its new minaret, more than 70 feet tall, towers over the street. When completed, the facility will encompass an entire city block.

Part of the fundraising comes through the pastries that Hasan wakes up around 6 a.m. to bake: bean pies. The pies are symbolic and tasty tether to his days in the Nation of Islam and date back to the 1930s, when Elijah Muhammad told followers to stick to a healthy diet and promoted eating navy beans.

When Nation of Islam members started to open restaurants, the pies were prominently featured. Some young men also sold them on the street.

Hasan’s recipe is his own, adapted from an imam he knew in New York (whose recipe, he says, had “too many ingredients”). Every Tuesday, he steps into the kitchen at the masjid, dons a white apron and throws the mini pies into the oven to raise money for the masjid.

He raised $14,444.25 for the Islamic center’s construction fund in two years — a figure he shares with as much pride as he has for the pastries themselves.

The pies have earned a reputation in the community. About two years ago, Saafir recalls, Islah held a bean pie contest during a festival. Hasan entered. And won.

“For me, that’s a beautiful thing,” Saafir says with a laugh. “Imam Hasan has put in a lot of work. When I’m older, I want to make some pies.”

The young imam refers to his elder with reverence, affectionately shortening Abdul Karim Hasan to “Imam A.K. Hasan.” As he gets older, Saafir says, he has come to appreciate and wonder how someone “can stay in position of power that long.”

“I’m interested in what sustained him in that position, after having experience now,” he says. “When I see him, it’s like my uncle. I have the utmost respect. That is where it all started, right there.”

Earlier this summer at a celebration of Eid al-Adha, which honors Ibrahim’s obedience to God in being willing to sacrifice his son Ismael, Hasan walks among the congregants who have gathered under white canopies pinned with pink and turquoise balloons in Bilal’s parking lot.

“Hasan is valuable to us. He has so much goodwill going for him,” says Aadil Naazir, executive director of the Center for Advanced Learning, the school on Bilal’s campus.

To Naazir, Hasan “represents our history.”

“We were youth when we started with him,” says Naazir, 72. “He’s a connection to the past and present.”

Naazir pauses, then nods in the direction of Islah mosque five miles away. While Hasan links his congregation to the last century’s great social justice struggles, he says, Saafir is looking for new ways to carry that faith forward.

“He represents the future over there,” Naazir says.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.