A California in crisis awaits Newsom after landslide win in recall

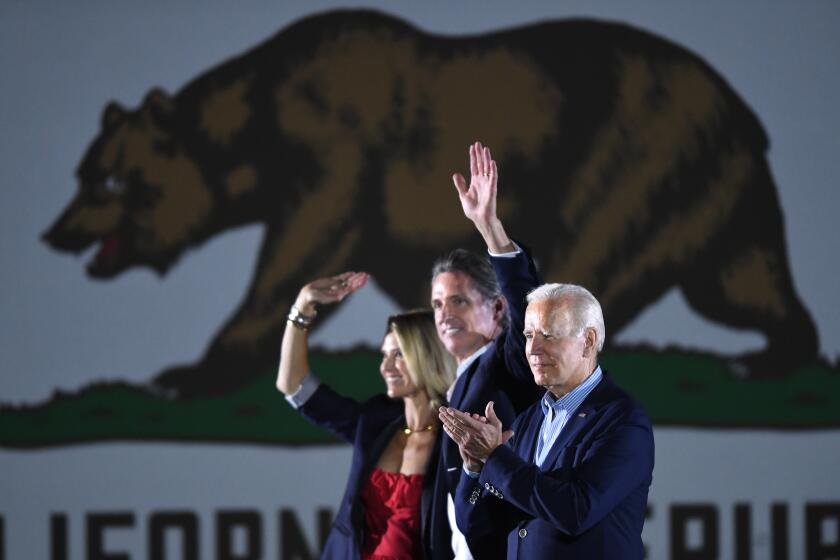

SACRAMENTO — Standing in an elementary school classroom in Oakland, Gov. Gavin Newsom paused when asked if he felt vindicated after voters saved his political career the night before and handed him a landslide victory in the recall election.

“I feel enlivened. I feel more energized, and I feel a deep sense of responsibility because people are counting on us and they need us. They need government, effective government,” Newsom said. “I’m also mindful of this: Challenges are in abundance in these positions.”

California voters and Newsom’s political allies stepped up to defend the governor from the GOP-led recall, delivering a win that helps pave the way to his reelection next year. Battle-tested but not bruised, the 53-year-old reaffirmed the mandate he walked into the governor’s office with three years ago after notching what appeared to be an even greater margin of victory Tuesday.

But just as wildfires, punishing drought, record homelessness, a housing shortage, a once-in-a-generation pandemic and a learning curve at the Capitol have challenged much of his term in office, Newsom returns to work facing those same problems and more.

“He has the same things to deal with today that he dealt with yesterday, minus the recall election,” said Dana Williamson, who worked as Cabinet secretary to former Gov. Jerry Brown. “I would think the election gives him a boost of confidence. He’s coming out of this in a stronger place than when he entered it, and it leveled his political playing field.”

With at least $24 million in his 2022 reelection campaign account and an activated army of union volunteers, Newsom will be a formidable incumbent when voters return to the polls next year, raising doubts that a well-known intraparty rival will step up to challenge him.

The recall campaign against Gov. Gavin Newsom was supposed to unify California Republicans. Instead, it deepened divisions between the party’s grass-roots conservatives and moderate establishment.

Newsom could also end up running against a cast of Republican candidates similar to the one he trounced Tuesday, some of whom have already announced their intentions to challenge him.

“There is no reelect after this,” said Dustin Corcoran, chief executive of the California Medical Assn.

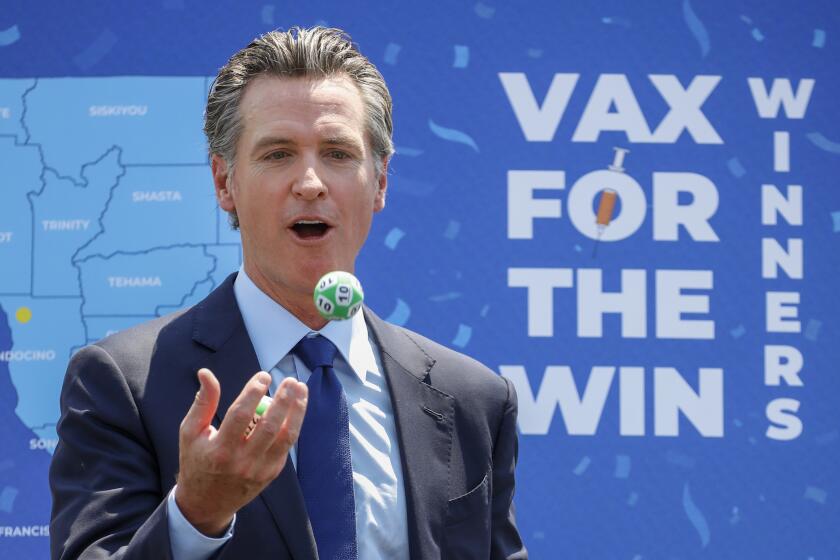

Newsom’s campaign framed the recall as a proxy war against Trumpism playing out in a deep-blue state, shifting the focus off Newsom and his own record.

The governor took advantage of Larry Elder’s candidacy to contrast his leadership during the pandemic to the conservative talk show host’s promises to rescind mask mandates in schools and reverse the vaccine and testing rules Newsom ordered for healthcare workers, state employees, and teachers and school staff.

The decision to attack Elder’s position on vaccines proved smart in California and provided Newsom with an opportunity to tap into fears about the Delta variant and frustration with the unvaccinated. A recent preelection poll from the Public Policy Institute of California found strong support for requiring proof of vaccines for large outdoor events and to enter indoor businesses and predicted 80% of likely voters would be vaccinated.

“The campaign seized on that to create a simple choice for voters,” said Ace Smith, one of Newsom’s political advisors.

A week before the election, Smith argued that Sept. 14 would give Newsom “a clear mandate not only against the recall, but for sanity on something as important as public health.”

As a “final seal of approval” for his handling of the pandemic, Newsom’s triumph will also make it harder for Republicans to gain any traction during his reelection campaign with claims that he was too restrictive or took away personal freedom, said Juan Rodriguez, Newsom’s campaign manager.

Higher vaccination rates correlated with higher support for Gov. Newsom in the recall election, and vice versa, analysis of voting data shows.

The first governor in the nation to issue a statewide stay-at-home order, Newsom might be emboldened by Tuesday’s win to accelerate his approach to fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

Democratic strategist Robin Swanson said many Californians, even Newsom supporters, are still frustrated from the school closures and shuttered businesses. She said the governor would be smart to acknowledge those feelings.

“People want to be heard in elections and the most gracious victors hear what their opponents say and hear what people say who didn’t vote for them,” Swanson said. “That’s how you build the sort of unity and healing that our state needs.”

In his brief election night speech, Newsom said he was humbled and grateful to the Californians who exercised their right to vote and expressed themselves “by rejecting the division, by rejecting the cynicism, by rejecting so much of the negativity that’s defined our politics in this country over the course of so many years.”

He extended more of an olive branch Wednesday.

“Coming out of this recall, I want to turn the page and express respect and a deep sense of responsibility not just to those that voted no on this recall, but those who voted yes,” Newsom said. “They matter. I care and I want them to know I’m going to do my best to have their backs as well.”

Newsom said very little during the campaign about his agenda for the final year of his first term, demonstrating an unusual discipline for a governor who earned a reputation for overpromising in the run-up to the 2018 election and for taking swings at every pitch once in office.

His governing style led to criticism that he was a scattered leader with more priorities than his staff could handle, resulting in incremental progress instead of the blockbuster results he promised and that Californians came to expect from him. Even before he took office, Newsom predicted in a New Yorker article that his “biggest threat to being a successful governor is my profound incapacity to distill what I want to accomplish into one or two issues.”

The campaign is over. And what Gov. Gavin Newsom takes from what happened — what he does or doesn’t learn from it — will affect millions of Californians.

In an interview days before the election, Newsom rejected the idea that he should refocus on a smaller plate of objectives.

“Oh no. Because, to me, it’s not a criticism I embrace or accept,” he said. “It’s not a self-criticism, quite the contrary.”

On Wednesday, the governor said he had asked the elementary school students to name the top three issues in the state of California.

“I’m not making this up,” Newsom said. “They said, climate change, homelessness and education funding, and then they added in, to their credit, sexism, racism and healthcare. You don’t need focus groups. You don’t need public opinion polls to tell you what you need to focus on. And I want folks to know that’s exactly what we’re focused on in this state.”

The governor added that the election gave him a greater awareness of the limited time he has to accomplish the goals he campaigned on in 2018. He’s mentioned his renewed sense of vigor to address housing, homelessness and climate change, in particular.

In a state battered by worsening drought and uncontrollable wildfires, Newsom has tough decisions ahead.

He spoke often in the final days of the campaign about the climate crisis, which some of his aides said will become more of a focus as he finishes out his first term and begins to step out of the shadow of Brown’s climate legacy.

Facing expectations that the drought will only get worse next year, Newsom will likely have to do more than ask residents to voluntarily cut their water usage.

Newsom won by stoking fears of the GOP to turn out his base, and by touting his handling of the pandemic. Would the strategy work outside California?

“The dire situation of this year’s drought is really just a prelude to a much more consequential drought next year,” said Daniel Zingale, a former adviser to Newsom who serves on the Delta Stewardship Council. “This is the year where a lot of our storage is being depleted, but it really hits the state harder next year and it will require the governor and others to figure out how we’re going to deal with that.”

At the same time, Newsom will be forced to contend with the ever-present threat of wildfire. The number of acres burned this year is currently behind the total at this point in 2020. But strong winds and dry conditions in the fall could mean more devastating fires on the horizon.

And despite sky-high promises by Newsom in 2018 to fix homelessness and build more affordable housing, more people are on the streets and homeownership continues to remain a pipe dream for many Californians. Newsom campaigned on single-payer healthcare three years ago and Democrats in the Assembly could push a bill next year to establish the model in California.

Ultimately, whether Newsom can use the recall to make progress on the biggest problems largely hinges on whether he chooses to lead as the captain of the Democratic team and shore up some of his rocky relationships with the Legislature and interest groups at the Capitol.

The Service Employees International Union pointed out the day after the election that rank and file workers and grassroots volunteers deserve credit for turning out voters. In a Zoom event Wednesday morning, they said their efforts resulted in over a million conversations with voters in the eight weeks leading up to election day.

“Last night’s victory was for a victory for working people and by working people,” said Max Arias, executive director of SEIU Local 99.

Arias said workers didn’t campaign for Newsom with any specific asks or expectations of him going into the next year.

“They turned out because that’s exactly how we build power,” Arias said. “We expect and hope that the governor will continue to work in partnership with working people to continue to improve the lives of working people and the lives of all Californians.”

But three months earlier Arias and union workers rallied for childcare workers at the Capitol, calling on Newsom to finalize their contract and raise rates. The leaders of the state Senate and Assembly spoke at the rally in agreement with the workers.

At the time, Arias said childcare workers supported the governor but were “disappointed and confused” by his lack of action and “ready to fight.”

The governor eventually reached an agreement with the union, but the episode epitomized the tensions in Sacramento. The governor’s go-it-alone approach to dealing with the pandemic and the scramble to figure out the details of his policies at times heightened those feelings of distrust and frustration.

The recall election required the governor to rebuild a diverse coalition of unions, Realtors, developers, tribes and other groups that have funded his campaigns, and it’s also given him the benefit of a clean slate.

“You don’t enjoy these things when you’re going through them, but sometimes, you know, when you look back, you could be at the beginning of something better,” Zingale said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.