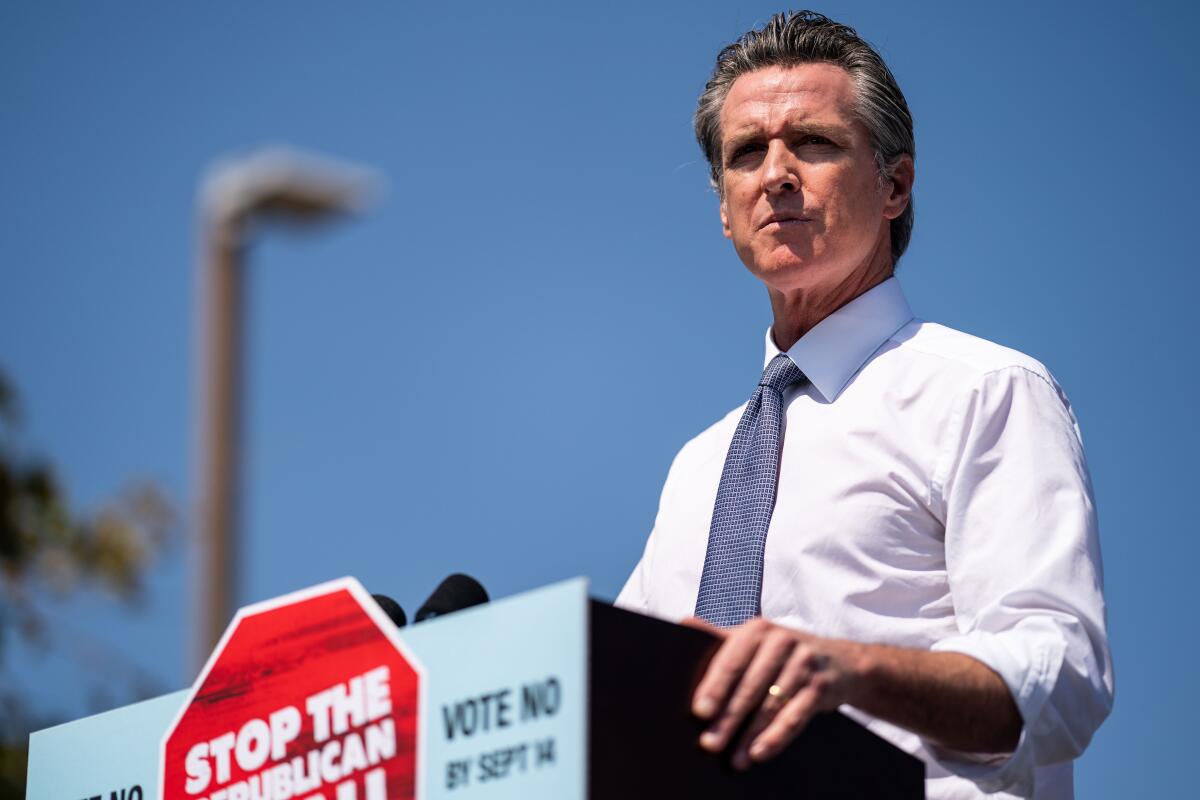

Newsom stakes his future on one simple argument: Fear a GOP governor

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Gavin Newsom warned in the Bay Area that electing Larry Elder would have deadly consequences for Californians amid the still-raging COVID-19 pandemic.

In Los Angeles, he painted the recall as a battle against “Trumpism” that could plunge the state into an uncharted, near-apocalyptic future. And in ads, his campaign has cautioned that failing to vote could mean the state ends up with an “anti-vax Republican governor.”

As he barnstorms the state, Newsom’s strategy to generate fear about a GOP takeover appears to be working to turn out Democratic voters, allowing the governor to avoid more complicated conversations about his own record.

With his governorship beset by record wildfires, poor marks on addressing homelessness and an 18-month struggle to contain virus transmission in the state, Newsom and his political advisors have sought to reframe the election as a vote on Republicans since before the recall even qualified for the ballot.

“It was about making the campaign a referendum on the opposition, not just kind of a dunking booth exercise on the incumbent and making a campaign about the stakes, what this means for California if this recall were to go through,” said Sean Clegg, a senior political advisor to Newsom.

If Newsom prevails on election day, political observers say his survival should be credited to cut-throat strategy, a multi-million dollar advertising blitz and a little luck.

Newsom’s campaign team successfully kept other well-known Democrats off the ballot, a move that ensured the governor wouldn’t lose votes to an intra-party rival and gave him the ability to cast the recall squarely as a GOP power grab led by Trump supporters and radical right-wing groups.

Then, just as polls this summer raised the specter that anti-Trump messaging might not be enough to overcome Republican enthusiasm for the recall, Elder walked into the race and embodied everything the governor was trying to make Californians afraid of.

“It proved this was not just rhetorical scare tactics, that there really is someone who is as dangerous as Trump and would be governor if this recall succeeds,” said Dan Newman, a spokesman for the governor’s political campaign.

Newsom’s team of political consultants say they modeled the campaign after former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s successful offensive against labor unions that sought to oust him in a 2012 gubernatorial recall. Instead of defending his own record, Walker shifted the conversation away from himself and attacked his opponents.

Gar Culbert, a professor of political science at Cal State Los Angeles, said it’s often easier to inspire turnout with negative campaigns against an opponent than positive campaigns touting a candidate’s achievements. In a state where registered Democrats outnumber registered Republicans nearly 2-1, the recall will hinge on which side does a better job of inspiring its base to vote.

But Culbert said generating fear about Trump after Democrats mobilized to vote him out of the White House in 2020 is more difficult than it seems.

“They’re done,” Culbert said. “They won their battle. And now they’re ready to enjoy it. You’re now asking people to turn out again, and the people who are paying attention are the people who lost in 2020.”

When Newsom’s campaign launched their scare tactics early this year, Kevin Faulconer, a moderate Republican and former mayor of San Diego, was the biggest known threat on the ballot.

Now, with Elder on the ballot and in the headlines, Democrats joke that Newsom could quit campaigning all together. But things weren’t looking good for Newsom’s campaign before the conservative talk radio host announced his candidacy in mid-July.

Anticipating that California would come “roaring back” from the pandemic before the state’s reopening, the governor’s campaign launched a positive ad in May touting Newsom’s budget plan to give stimulus payments to families and businesses, expand free prekindergarten and invest in solutions to homelessness.

The positivity was short-lived. The Delta variant emerged and eliminated any hopes California would move past the pandemic by election day. In late July, a UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll suggested Californians were almost evenly split on whether to keep or remove Newsom from office.

Newsom’s political advisors said the rise of the Delta variant forced the campaign to move away from the rosy messaging around the governor’s budget comeback plan. But it also provided them with an opportunity to trumpet Newsom’s leadership on COVID-19 and label Elder his antithesis.

“The Delta variant changed everything and it became the line of scrimmage in this election,” Clegg said.

Elder has vowed to immediately rescind the state’s public school mask mandates and vaccine requirements for state and healthcare workers. At the same time, the governor polls above 50% for his pandemic response.

“He peddled deadly conspiracy theories and would eliminate vaccine mandates on day one, threatening school closures and our recovery,” claims an ad that has also run in Mandarin, Korean, Cantonese and Spanish and feature a picture of Elder standing next to Trump.

“There’s a clear binary choice,” Newman said. “We can keep on the progressive path recovering from COVID or wrench the wheel hard right and go off the COVID cliff toward Elder, Trump and Florida.”

In the months before Elder’s campaign kicked off, some within the Democratic Party felt that California needed an insurance policy in the event that Newsom was recalled.

A poll conducted in late April and early May showed twice as many Republicans as Democrats showed high interest in the recall and 57% of voters believed Newsom was doing a poor or very poor job handling homelessness.

In addition, nearly half of Democrats surveyed wanted a prominent Democrat as a replacement candidate in the race. The feeling didn’t go away: A recent poll conducted by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California found that 63% of likely Democratic voters say they still aren’t satisfied with the replacement candidates on the recall ballot.

Subscribing to the theory that Democrat and then-Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante’s candidacy helped sink former Democratic Gov. Gray Davis in 2003, Newsom’s political advisors aggressively opposed the possibility that other well-known candidates from within the party should run. Newsom’s campaign and the California Democratic Party have also told voters not to answer the second question about a replacement candidate on the ballot.

The strategy left Democrats with a choice to keep their governor or recall Newsom and end up with a Republican. And by advising them to not pick a backup candidate, a favorite among Republican voters, most likely front-runner Elder, could end up governing California if Newsom is recalled.

“I think many that are around today were around in 2003, obviously in a different scenario and different landscape than we are today,” said Rusty Hicks, chair of the California Democratic Party. “The idea of the ‘reliable alternative’ was a lesson, good or bad, that many carry. Our focus is not on alternative candidates. It’s on defeating this on the first question and rendering the answer to the second question null and void.”

Garry South, a senior political advisor to Gov. Gray Davis, defended the campaign’s effort to keep other Democrats out.

“Jesus, folks, we’ve seen this movie before,” South said. “Take it from somebody who was there.”

Davis’ campaign similarly tried to label the 2003 recall as a GOP power grab, but Bustamante’s presence on the ballot “mucked up” that argument in the minds of voters, South said.

“The question we got in focus groups was ‘How can it be a Republican recall if his own Democratic lieutenant governor is running against him?” South said.

Some Democratic voters also thought they could trade Davis for Bustamante, but didn’t end up with either as governor.

Former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa raised concerns that he might spoil the Newsom campaign‘s plan to shut out other Democratic contenders when he tweeted in March that California needed to open schools. At the time, Newsom was under fire for not opening schools fast enough and Villaraigosa’s comments created speculation that he might step into the recall race.

In response, Clegg tweeted that his “old friend Antonio will embarrass himself and forever poison his legacy if he runs.”

Mike Madrid, a Republican political advisor to Villaraigosa, said he viewed Clegg’s response as a sign that Newsom’s standing might not be as strong as expected.

“Methinks thou doth protest too much,” Madrid said. “They were overplaying their hand. I don’t think anyone was seriously considering it until they started to show publicly that there was a reason to be concerned. At that point, yeah, we took a look at it. Everyone took a look at it. It was like, what are they afraid of?”

Villaraigosa ultimately decided not to run and publicly endorsed Newsom’s fight against the recall. But Madrid said it’s clear that Newsom’s team knew earlier on what the polls would reveal months later: more motivated Republican voters and his own weaknesses on homelessness and other issues.

Clegg and other Newsom advisors say what some viewed as an enthusiasm gap was more of a voter awareness problem given that the date of the election wasn’t set until July and many Californians are unfamiliar with recall elections.

He also said it’s common for the party in power to deal with apathy and complacency from its base, while the opposition is more energized.

“We’re activated and motivated by things we fear, by negative information more than positive information,” he said. “Larry Elder’s world view is more unpopular than the governor is popular.”

With the emergence of Elder in the race, Newsom’s advertising blitz underway, national Democrats campaigning alongside him and thousands of volunteers knocking on doors and phone banking to encourage turnout, polls suggest the governor may be on strong footing less than a week before the election. And if voters have tired of the fear mongering, they‘re not alone.

“My wife can’t take the negative,” Newsom recently told the Los Angeles Times Editorial Board. “She just wants me to say, ‘Well, tell them everything you’ve done right.’”

The governor has said he’s waiting until his reelection to run on his record, even if he wishes he could be talking more about it now.

“Well, you know, look: I’d love to be making that case 24/7,” Newsom said. “But look, at end of the day, we’ll be judged on the last 18 months, disproportionately. I’m not naive about that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.