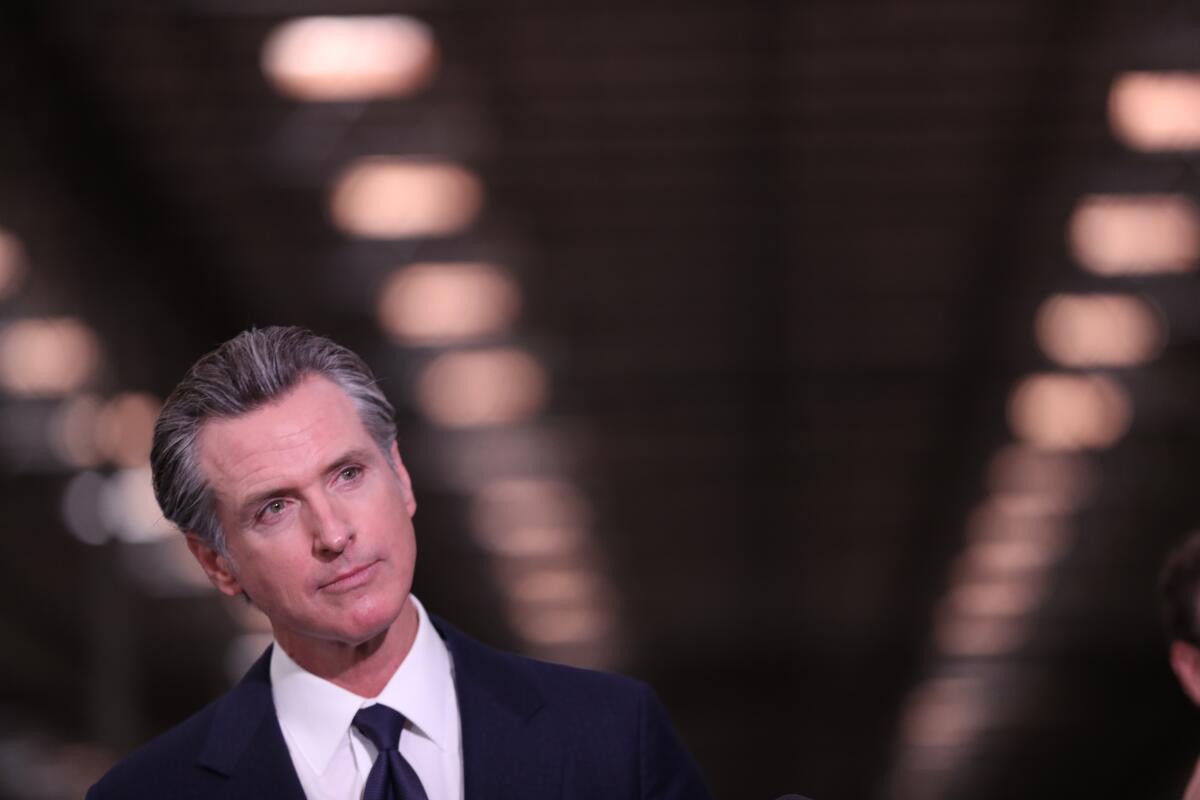

After being tested and singed by fire as California’s governor, Newsom seeks another term

SACRAMENTO — Four years ago, Gavin Newsom delivered an election-night acceptance speech that promised to make California “a place of opportunity, safety and affordability for everyone,” ending a gubernatorial campaign stuffed with audacious policy goals.

Less than 36 hours later, as acting governor, he was leading the state through a trio of tragedies that took more than 100 lives: a mass shooting in Thousand Oaks, a wildfire that barreled through Malibu and the devastating Camp fire in Butte County.

“That’s a bit of baptism by fire, isn’t it? Quite literally, not figuratively,” Newsom said in a recent interview, days before voters cast their ballots in the November election. “Gunfire. Wildfires.”

In the midst of a reelection campaign, Newsom insisted he wasn’t in a reflective mood. But then he drifted back to those fatal events 60 days before he took the oath of office.

That time served as a “preview of things to come” in a first term dominated by extraordinary crises, Newsom said. It prompted a sober realization of his obligation to respond to the problems that arise in the moment, regardless of his ambitious plans to restore California’s grandeur.

Those plans likely did not include declaring at least 54 states of emergency in California in response to wildfire, extreme heat, rainstorms, drought, earthquakes, riots, oil spills, monkeypox and COVID-19 since his inauguration on Jan. 7, 2019.

“I know that there was obvious frustration, and justifiably so, when you want to come in and move things forward,” said Dustin Corcoran, chief executive of the California Medical Assn. “Instead of having a positive vision, you have to deal with how to make the world not collapse. It’s a really hard mantra to go out and say, ‘Well, your life could have sucked more if it wasn’t for me.’”

Ann O’Leary, former chief of staff to Newsom and a longtime staffer for Hillary Clinton, said the underlying tension of the governor’s first term has been defined by his attempts at finding ways to execute his progressive campaign promises amid that near-constant state of disaster.

“I think, immediately, from literally day one of him winning the election, it was very clear that we were going to be having to do both,” said O’Leary.

Newsom, who says he’s always “in a hurry” to take action, refused to allow disasters to beset his agenda and stubbornly rebuffed advice to narrow his policy goals. With California’s booming economy and Democrats’ iron grip on the Legislature, he was eager to take advantage of the state’s flush tax revenue while it lasted.

Over the last four years, Newsom passed a slate of policies unsurpassed by any governor in modern state history: the expansion of Medi-Cal to cover all immigrants, the creation of CARE Court to force the most mentally ill and drug-addicted unhoused Californians into care, a sizable expansion of paid family leave for parents of newborns and those caring for sick relatives, stronger gun safety measures, two years of free community college, free preschool for 4-year-olds and a phaseout of new gas-powered cars.

But his policies have yet to produce the kind of results Californians want to see.

Though the COVID-19 crisis allowed the state to seek new ways to house the homeless, sidewalks in big cities are still lined with tents, and the number of unhoused has grown. Newsom has fallen far short of the progress needed to meet his campaign promise to build 3.5 million homes by 2025, a goal he redefined as a “stretch” after the election.

The governor’s opponent in this year’s race, state Sen. Brian Dahle (R-Bieber), has repeatedly criticized Newsom for worsening crime rates. The California Department of Justice’s recently released 2021 crime report showed that homicides and aggravated assaults shot up, driven largely by gun violence, from pre-pandemic figures.

“I would give this governor an ‘A’ for effort and an ‘A’ for sizzle,” said David McCuan, chair of the political science department at Sonoma State University.

He describes “sizzle” as Newsom’s knack for attention-grabbing, first-in-the-nation announcements and the news conferences he held during the pandemic, in which he unveiled initiatives sometimes on a daily basis.

McCuan gives Newsom a “C” for execution.

“I think he reflects the dilemma that is California: On the one hand, delivering this robust bounty and envisioning and epitomizing that American dream and, on the other hand, framed by chronic challenges of homelessness, housing, affordability.”

Newsom’s desire to write his own narrative became widely apparent from the moment he took office.

In his first three days as governor, he sent out a flurry of announcements taking on Medi-Cal prescription drug costs, promoting equity in assessing wildfire risks in communities, expanding the state’s healthcare system for low-income Californians and reinventing the “troubled” Department of Motor Vehicles, which had come under scrutiny for long wait times and subpar service.

But in his second week, his administration was hit by its first major crisis, when Pacific Gas & Electric announced its intent to file for bankruptcy.

The bankruptcy placed Newsom in a perilous political position. He had to appear tough on a company that has been responsible for numerous wildfires and, at the same time, push the Legislature to require ratepayers to shoulder $10.5 billion in costs to protect the utility’s financial future amid pressure from Wall Street.

“Credit ratings companies painted all these doomsday scenarios,” said Mark Toney, executive director of the Utility Reform Network. “The governor was between a rock and a hard place.”

The Democratic Legislature passed the law with overwhelming support, demonstrating the first signs of Newsom’s ability to sway lawmakers and advocacy groups to support his controversial causes. But Toney, whose group supported the bill, is frustrated that Newsom’s office didn’t stick to its word and require higher transparency standards for a new entity created to hold utilities accountable.

“We feel like there were promises made that haven’t been kept by the governor’s office,” Toney said.

That notion of overpromising became a common criticism of Newsom in his first year, which supporters and foes felt was more frenzied and uneven than anticipated as the governor took on dozens of issues at a time.

Daniel Zingale, one of Newsom’s top advisors during his first year in office, counseled the governor to narrow his priorities. But Zingale now says Newsom was right to ignore his advice.

“Each governor is unique,” Zingale said. “And as it turns out, this governor in these times didn’t have the luxury of choosing a few things.”

The troubles would only get worse for California as time went on.

“The second year, COVID slammed down on us,” O’Leary said.

Without direction from President Trump, Newsom on March 19, 2020, announced the most consequential government action in modern state history: Nearly 40 million residents were ordered to shelter in place until further notice.

Effectively shutting down the world’s fifth-largest economy carried enormous political risk and marked a watershed moment for Newsom and California. Newsom and his aides felt it was necessary to slow the spread of COVID-19 — a mysterious, deadly disease with, at the time, no vaccine or known effective treatment — to prevent hospitals from being overrun with sick and dying patients, as was happening in New York and other parts of the world.

In the coming months, California saw a much less deadly first surge of COVID-19 than other parts of the United States. Newsom held daily news conferences and won national praise for his leadership, as he was hailed among Democrats as the antithesis to Trump.

But the accolades for Newsom began to dim as weary Californians struggled through months of restrictions and closures that froze lives in place, devastating businesses and putting millions out of work, postponing weddings, isolating the elderly and forcing children into distance learning.

Newsom’s decisions increasingly came under scrutiny. Bolstered by his choice to dine with lobbyist friends at the Napa Valley’s French Laundry restaurant while advising Californians to avoid mixing with other households, Republicans forced a vote to recall the governor the following year. Rolling blackouts, extended school closures and his administration’s complicated web of requirements for businesses to reopen frustrated and confused voters.

Newsom portrayed the campaign to oust the governor as a “life and death” battle against Trumpism and far-right antivaccination activists, and he seized on the top Republican trying to replace him, conservative talk radio host Larry Elder.

He attacked Elder for being a political ally of Trump, with whom Newsom publicly sparred during his first two years in office. Newsom criticized Elder for his opposition to abortion rights and to COVID-19 vaccination and mask mandates.

The approach worked, and Newsom beat the recall by more than 3 million votes, but the Republican-led effort hardened him, he said, and showed him “a ruthlessness on the other side that I understand now.”

Newsom quickly launched an offensive against Republican governors across the country, accusing Ron DeSantis of Florida and Greg Abbott of Texas, among others, of bullying immigrants and LGBTQ Americans and trying to dismantle civil rights protections.

Those high-profile attacks stoked speculation about Newsom’s presidential ambitions and endeared him to Democrats who want to see their party do more. His focus beyond the state inspired criticism from Dahle and others that he’s more devoted to running for president than to fixing problems in California — which Newsom denies.

As for governing through crisis over four years, the 55-year-old said it was easier than serving eight years as lieutenant governor, in a largely ceremonial position. Stepping into the role of governor the day after the election, even in an acting position, was a “very familiar, interestingly comfortable space,” he said, and felt similar to his days as mayor of San Francisco.

“That’s the space,” Newsom said. “That’s why you go through the process of politics. Finally, that position where we can do something about it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.