Newsom recall election tests the California dream

California has always been on a fast track to the future. Let other Western states slowly come into focus, the 31st arrived fully formed on the merits of gold and the thousands of immigrants who pursued it.

Their dream was simple, difficult and commonly shared. They wanted to discover the happiness that economic security affords. Some succeeded; many more did not. But the lessons of that engagement have endured.

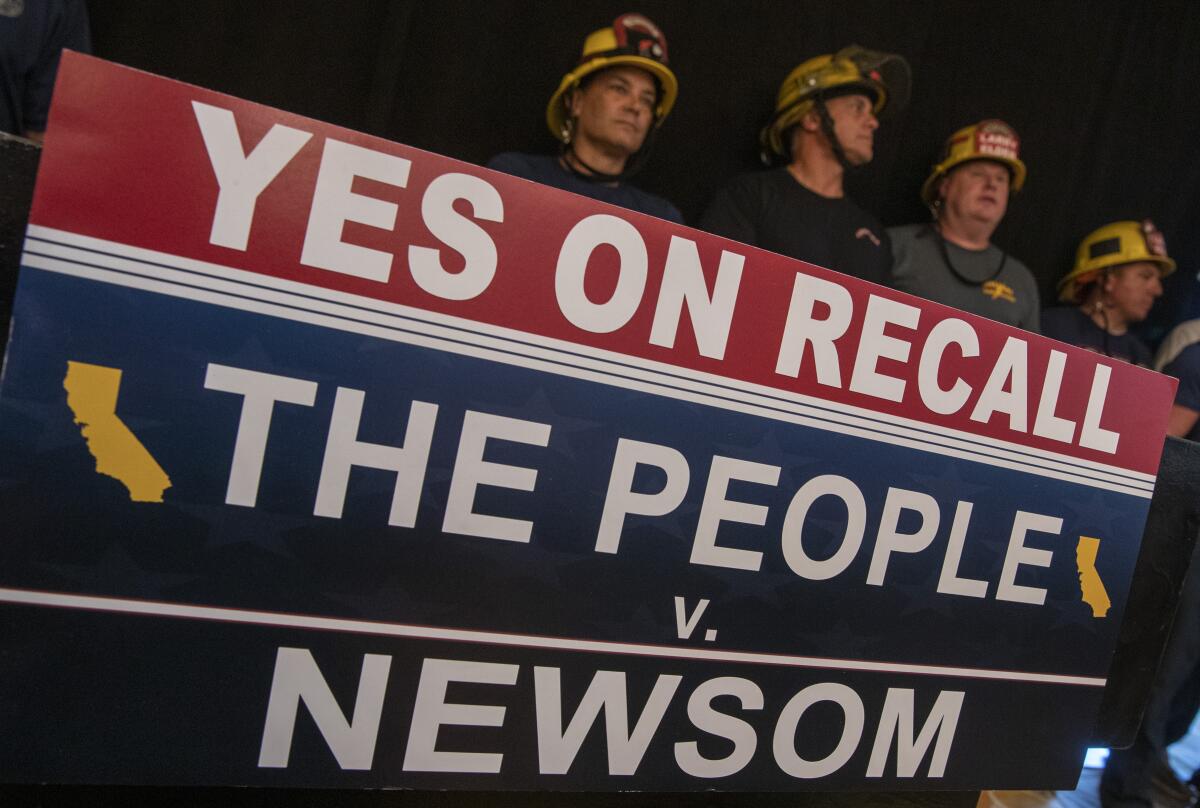

When 1.6 million voters signed a petition to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom, they signaled their indebtedness not just to century-old political reforms but also to a spirit of restless reinvention that took root 170 years ago.

“Californians,” said historian H.W. Brands with the University of Texas at Austin, “have learned to be impatient with patience. The idea of sticking to an unsatisfactory status quo doesn’t stick.”

Taking risks was the quickest path to success and evidence of failure was reason to move on and try again, an impulse that has cut a deep channel in the California psyche. Evidence can be found in today’s recall election, said Brands, author of a history of the Gold Rush.

“If you don’t like this governor,” he said, “don’t wait until the end of his term. Throw him out.”

As voters cast their ballots, some may sense that the reason for the recall effort has less to do with the governor’s performance than a broader dissatisfaction with 10 years of Jerry Brown’s and Newsom’s administrations.

With Democratic supermajorities in Sacramento and a Democratic governor, those voters might have felt slightly removed from the partisan rancor dividing other states, but the last five months — with a $276-million projected expense and 46 candidates making their case — have spoiled that illusion.

Filter out the static and a bipartisan picture emerges of an electorate struggling to address the most challenging issues California has had to face. Climate change and catastrophic wildfires, a housing crisis and a homelessness crisis, income inequality and racial inequities have reached a point where any proposal that doesn’t lead to a fix is reason to mobilize.

“Much of everyday life seems at risk,” cultural historian D.J. Waldie said, “and Californians are not accustomed to being fearful of the future.”

Californians amended their Constitution 110 years ago to allow ballot initiatives, referendums and recalls.

Little does it matter that the odds for the recall are long — of past attempts only one has succeeded — or that problems festering for decades often take longer to fix. Hopelessness and resignation challenge the notion of California’s exceptionalism and another aged trope.

“Not many states have the word ‘dream’ associated with them,” said Mark Baldassare, president and chief executive of the Public Policy Institute of California. “We have the American dream, but there is something special about the California dream. We are better, we can do better, and we aren’t. That’s pretty disappointing.”

Never mind that the dream seldom matched the reality.

Once considered a state of rugged, can-do individualists, California was built by federal subsidies that developed its water resources, electrical grid and agribusiness empires, and during its most golden age, the boom years from the 1950s through the 1960s, economic and educational opportunities were restricted by race and ethnicity.

Yet the dream endures. Like miners standing at a millrace, Californians look for speedy solutions, so the idea that change takes time is “lost in translation,” Baldassare said. “We are less sensitive to markers of progress than we are demanding some conclusion.”

By undoing what Newsom has done — “implemented laws which are detrimental to the citizens of this state and our way of life,” according to the petition to recall — advocates believe removing him from office will address the problems facing the state. Their rallying cry is familiar; it lies at the intersection of race, political opportunism and the economy.

The petition specifically charges the governor with endorsing laws that “favor foreign nationals, in our country illegally, over that of our own citizens”; imposing “sanctuary state status” on California; and failing to enforce immigration laws.

Jessica Kim, a history professor at Cal State Northridge, recognizes the subtext. “There is a common trend in California politics of thinking about limited resources especially in terms of what those perceived as being foreign are taking from us,” she said.

In the 1870s, when an economic depression hit California, workers in San Francisco headed by an Irish demagogue attacked Chinese and other Asian immigrants living in the city.

In the 1930s, when drought and dust storms forced thousands to migrate to California in search of work, Los Angeles Police Chief James Davis sealed off the border, and in Sacramento, a bill was introduced banning “indigents.”

In 1994, when faced with a lingering recession and reelection, Gov. Pete Wilson ran ads of people running through the San Ysidro border crossing with a voiceover, “They keep coming.”

Today, the COVID-19 pandemic with lockdowns and mandates for businesses and schools has become the face of the recall effort.

But, Kim said, it has also become an “aperture to express long-standing political frustration, economic resentment, feelings of loss on the part of conservative whites who have watched the state within their lifetimes swing farther to the left.”

She cites the demographic shifts in the state over the last 30 years that have brought more Latino officials into office and led to a defiance of federal immigration agencies and an extension of benefits to immigrants in the country without authorization, including in-state tuition for those attending the Cal State universities.

Despite these refutations of former policies and political agendas, California’s emerging strength — its increasing diversity — has become its greatest challenge.

“When you have a place that has become as ethically, racially, linguistically and culturally diverse as California,” Waldie said, “you will find people who regard all of that as a risk to their expectations of whom they can become or a risk to what their children can become.”

Rapid change has left the electorate not so politically divided — the state is still solidly blue — as it is conflicted over what being blue means.

Pete Peterson, dean of the Pepperdine University School of Public Policy, sees the recall campaign not as the “last gasp of a Trumpist GOP” but “our first glimpse into a political realignment that has been developing over the last several years.”

By favoring “wine and cheese” constituents at the expense of its “beer and pretzel” voters, Peterson argues, Democrats have provided an opportunity for the Republican Party if it can “establish itself as the landing place for these disaffected Democrats and newly right-leaning, no-party-preference voters.”

“I’m not sure that will happen,” he added.

Former Assembly Speaker John A. Pérez sees a struggle taking place in the conscience of Democrats and Californians who are trying to understand what it means to be “the most multiracial, diverse and forward-looking state.”

“We pat ourselves on the back for diversity, but we struggle on how to make it real and equal,” he said, citing high COVID-19 mortality rates in communities of color as “an example of how we are still struggling with the tension around who we say we are and how we represent that.”

Pérez believes the answers will require a different perspective: “The challenges in the political discourse forward will not align with political discourses that have expressed themselves in the past.”

If so, then come Wednesday morning, Californians will find that the recall election brings little resolution, and maybe that will be fine.

This year, researchers at UC San Diego released results of a survey of 3,063 Californians, including 295 who responded in Spanish, meant to answer the question: Who still sees the California dream as working for people like them, and who sees the Golden State as tarnished?

At the time, the census had reported a decline in the state’s population; a congressional seat had been lost, and businesses and residents were relocating elsewhere.

Voters decide in California’s recall election whether Gov. Gavin Newsom will stay in office.

The numbers confirmed that while people in middle-income groups were the least optimistic, said Thad Kousser, a professor of political science at the university and a coauthor of the study, only 23% of the respondents said they were seriously considering leaving the state.

Perhaps the loudest voices in the room do not make a majority. Perhaps too a new California identity is being forged.

“Maybe some people in 2021, maybe those who are unable to reason through the risks and crises we experience, are not cut out to be Californians,” Waldie said.

To be a resident of the state is to be adaptable and to realize that California is not the land of popular ease. “California is a hard place to be,” he said. “We have to transform ourselves, and people don’t transform themselves easily.”

Reflecting back upon the experiences of the gold miners, historian Brands noted that embedded with their restlessness was the belief “that things can get better.”

Such optimism, he said, not only belongs “to those who went west to California but to every immigrant who went from one point to another.”

Fatalism, he added, is for “the ones who tend to stay home.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.