Leroy Harris Kelly III enlisted in the U.S. Army at age 17. He was married at 18. A father at 19. Dead at 20.

His parents, Guiselle Harris and Leroy Harris Jr., buried their son in the suit he wore to his senior prom at Azusa High School. His father had helped him pick it out — a bright white number with a long jacket, gold buttons and a black turtleneck.

On Sept. 11, 2001, nearly 3,000 people died after terrorists hijacked four jetliners, crashing two into the twin towers of the World Trade Center and a third into the Pentagon. The fourth plane crashed in a field in Pennsylvania after passengers revolted against the hijackers.

The Harrises still live in the townhouse where the young private first class grew up. It is a shrine to their dead child. Every day, Guiselle pins on a big round button that bears her son’s uniformed likeness and the words “Loving Memory Leroy.”

Every day.

For 17 years.

“I carried him for nine months,” Guiselle said. Before he enlisted, “he was with me for 17 years. I wish he was still here. Some people turn around and ask me, ‘Why do you still wear the pin?’ I say, ‘This is my hero. This is my baby.’”

Leroy was killed in Iraq on April 20, 2004, three years into the war on terror, three years after hijacked planes crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and a field in rural Pennsylvania, leaving behind a scar on this nation that has yet to fade and for families like the Harrises remains as fresh as ever.

As the 20th anniversary of Sept. 11, 2001, nears, the toll to the U.S. military in the war on terror — in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere — has reached a terrible peak. With at least 13 troops killed in the August suicide bombing at the Kabul airport, about 7,050 men and women in uniform have died in the “forever war.”

No state has lost as many as California; 776 men and women who called the Golden State home have died, 11% of the nation’s casualties. Nearly 20% of California’s war dead were old enough to die for their country but too young to buy a drink. They left behind 453 children.

A third of the troops who were killed in the Aug. 26 suicide bombing at the Kabul airport gate were Marines from California: Lance Cpl. Kareem M. Nikoui, 20, Norco; Cpl. Hunter Lopez, 22, Indio; Sgt. Nicole Gee, 23, Sacramento; Lance Cpl. Dylan R. Merola, 20, Rancho Cucamonga. It was the deadliest single attack against U.S. forces in Afghanistan in a decade.

Leroy died during one of the two bloodiest months for California’s military, according to California’s War Dead, The Times’ database of all this state has lost to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Twenty-two men were killed in April 2004; another 22 died that November.

The Black, white, Asian and Latino soldiers and Marines who lost their lives that April came from small towns and big cities, beach towns and the Central Valley. Their hometowns spanned from Vacaville in the north to Imperial in the south.

Four were immigrants like Leroy, who was born in Costa Rica and came to Southern California with his parents when he was 3 years old. In a nod to his heritage, he followed the Spanish-language tradition of using the father’s surname followed by the mother’s family name.

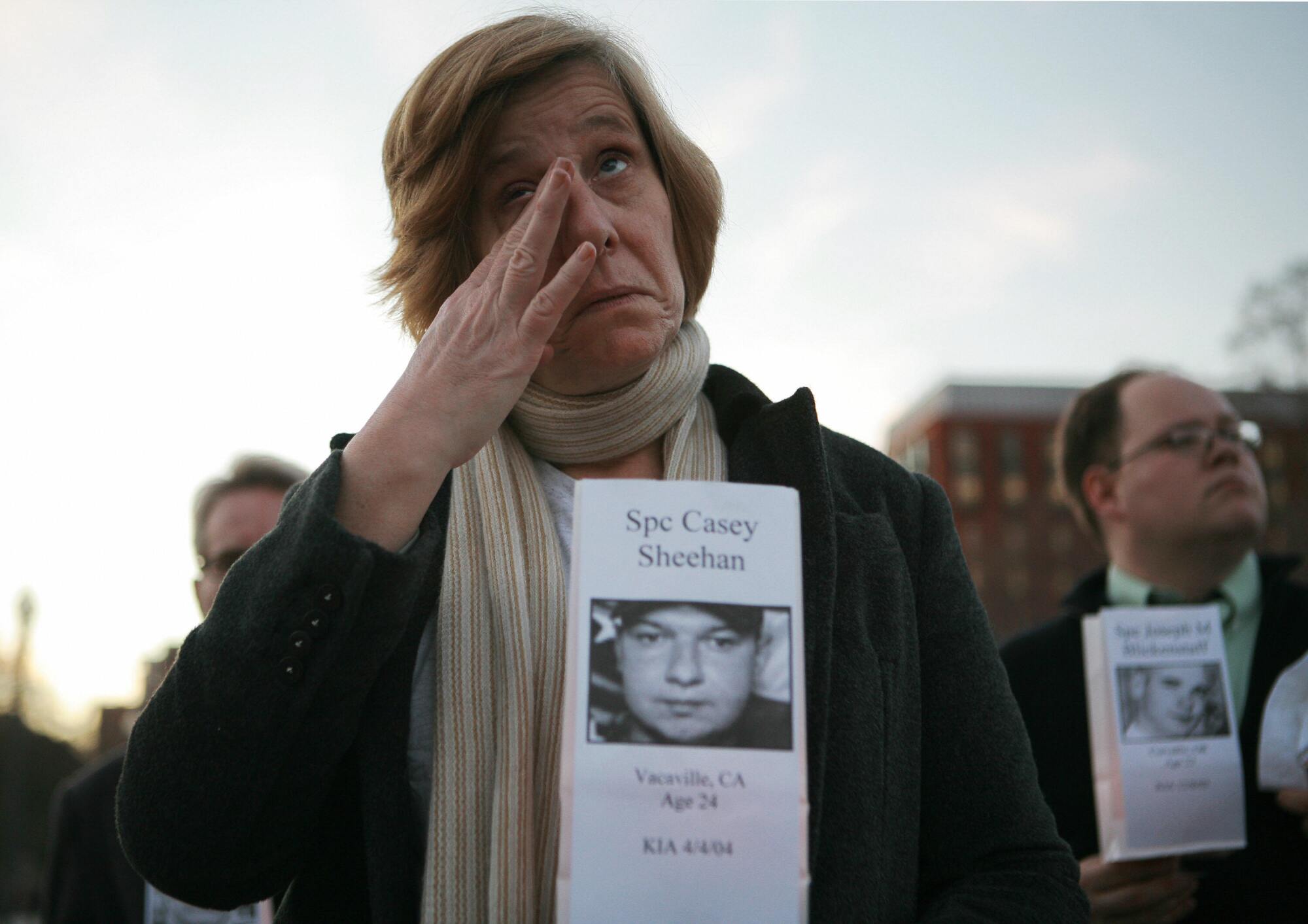

The first two Californians to die that month perished in Sadr City on April 4, known as Black Sunday, the largest casualty count in one day for the Army’s 1st Cavalry Division since Vietnam. Sgt. Michael Mitchell was killed by Iraqi insurgents; eight minutes later, Spc. Casey Sheehan died in the same attack.

Sheehan’s death created one of the fiercest antiwar activists of the era; his mother, Cindy Sheehan, set up a tent outside then-President George W. Bush’s ranch near Waco, Texas, and stayed there for more than a month, demanding an audience. Her years-long protests garnered international headlines.

Among the last Californians to die that month was Cpl. Pat Tillman. Six months after the Sept. 11 attacks, the football star put his NFL career on hold to enlist in the Army with his brother, Kevin. He was killed in eastern Afghanistan on April 22.

The official story? He was shot by enemy forces during an ambush. It was later revealed that Tillman was killed by “friendly fire,” his death covered up by the Army and the Bush administration.

For the families — and the state — the loss from the war on terror is incalculable.

“It’s not just about the soldier that was killed,” Cindy Sheehan said in a recent interview. “It’s about the ripple effect. And how did it hurt the families? How did it hurt the extended families? How does it hurt that all these Californians aren’t here?”

::

This is how it still hurts.

It is an evening in late July. Guiselle Harris has just arrived home from her job as a licensed dental assistant. Leroy Harris Jr. is at work. He’s a floor boss at Bimbo Bakeries USA, working swing shift at the company’s Pico Rivera distribution center.

Guiselle is alone in a townhouse filled with memories. The teddy bear dressed in desert camo a patient gave her in her son’s honor. The traditional folded flag. Her son’s trumpet, inscribed with his name, because the young musician was talented but also absent-minded. The framed letter to his younger sister Guisley; it is signed “Mighty Mouse,” the nickname an affectionate nod to his size and strength.

Then the photographs, so many photographs: Leroy in a tux, Leroy in camo, Leroy in full dress uniform, Leroy holding his newborn daughter Aalexis, his big body curled over her tiny, swaddled form.

Guiselle reaches for her smartphone, searches for the song with a permanent home there. It’s called “Some Gave All.” She hits play. Billy Ray Cyrus’ voice rings out.

All gave some, some gave all

Some stood through for the red, white and blue

And some had to fall

And if you ever think of me

Think of all your liberties and recall

Some gave all

She cries and cries.

::

Just days before the fifth anniversary of Leroy’s death, retired Staff Sgt. Paul E. Dowdle booted up his computer, found the young soldier’s page on The Times’ California’s War Dead website and began to write.

Tragically, I was with PFC Harris Kelly when his accident occurred and the precise moment of his unexpected and untimely death. The extent of his severe injuries were far greater to overcome than the 42 minutes of CPR that I personally administered to his young body along with the assistance of many officers in our unit.

Leroy was assigned to the 596th Maintenance Co., 3rd Corps Support Command, V Corps, in Darmstadt, Germany. His unit, Dowdle said in an interview, equipped and supported combat units, making sure weapons and vehicles were operational and ready for battle. On the day Leroy died, the 596th had finished its tour at the Taji base in Iraq and was in a convoy heading to Kuwait. Heading to safety.

Leroy was driving a truck with a canvas roof supported by “little metal bars,” Dowdle said. Sgt. Tyrone Worthen was in the passenger seat. They were pulling a trailer filled with water. The convoy was “in the middle of nowhere” when a sandstorm struck. The trailer flipped, taking the truck with it. Dowdle and his driver followed in the convoy’s last vehicle. They raced ahead to see what had happened.

“People were digging in the sand with their hands,” Dowdle said, describing the rescue as if it happened yesterday, not 17 years ago. “The guys who weren’t digging were guarding us with their guns.... I reached in and grabbed two male Black hands.”

As Dowdle pulled, one of the hands responded, tried to help Dowdle in the rescue effort. The other hand didn’t move.

Military deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan, 2001-Present.

“I thought, ‘Oh, wow. His arm is broken,’” Dowdle recounted. “I didn’t realize I had two separate people.”

Leroy Harris Kelly III and Tyrone Worthen.

When the truck was righted and the men released from the wreckage, Worthen was alive, conscious, cradling a “messed up” arm. Leroy was unresponsive. Lt. Megan Youngblood started chest compressions. Dowdle administered CPR for what “felt like forever.” A medic later told him it probably wouldn’t have mattered. The young man’s upper body had been crushed.

“It’s hard to think about,” Dowdle said. “I would breathe in. He would breathe it back to me. [The air] couldn’t go in, because he was crushed.... It sounds like groaning.”

Six months before the unit was deployed to war, its 239 troops spent much of their time on guard duty. Dowdle was the supply sergeant responsible for the soldiers’ weapons. As he waited in the basement for people to turn their weapons in, Dowdle said, he always knew when Leroy had arrived.

“I wish you could have heard him when he was coming down the stairs,” Dowdle said. Leroy would do a Michael Jackson imitation, singing “Smooth Criminal.” “He would put our names in the song. I don’t know anybody who didn’t like him.... He always made me laugh. He turned a day into a good day.”

Dowdle has another wish, “that his mother really knew what people did for him that day.”

::

Casey Sheehan’s death certificate reads: “KIA. Hostile fire. Gunshot wound to head.”

But the 24-year-old former altar boy who dreamed of being an elementary school teacher wasn’t the only casualty of that bloody ambush in the slums of Baghdad. When Casey died, his mother said, the Sheehan family died along with him.

“My husband and I got divorced,” Cindy Sheehan said in a video interview from Vacaville. “We were married for almost 30 years when Casey was killed. And I’m positive we’d still be married if Casey hadn’t been killed.... I was like, ‘We can go on, but we have to figure out a different way of being a family. Because we don’t have Casey, you know?’”

Casey was the oldest of four children. When he died, his sister Carly was no longer the oldest daughter. Suddenly, she was simply the oldest, Cindy wrote in her 2005 memoir, “Peace Mom: A Mother’s Journey through Heartache to Activism.” Andy went from being the youngest son to being the Sheehan family’s only son.

And Cindy? Her son’s death plunged her into pain and grief and numbness. She wrote about feeling “like a piece of rotted meat surrounded by flies and ugliness,” of feeling “wrung out and dehydrated by the tears that wouldn’t stop,” of being “paralyzed by my pain and longing.”

Longing for the son who loved pro wrestling and called it “soap operas for guys.” Whose Eagle Scout project involved planting 1,100 trees in the Angeles National Forest. Who, as a 7-year-old studying for his First Communion, would play Catholic Mass with his younger sister, using Wheat Thins for Communion wafers. Who thought about becoming a priest but decided he wanted a wife and children even more.

Who made her laugh. Cindy’s favorite Casey story — one of them anyway — was about dropping the kindergartner off at Catholic school. As they circled the parking lot, the little boy piped up.

Casey: “Look, Mama, there’s a parking space.”

Cindy: “Oh, we can’t park there, that’s a handicapped space.”

Casey: “Oh, that’s right. We’re not handicapped. We’re Catholic.”

It was her daughter, Carly, who helped Cindy claw her way out of the fog of grief. One day, when Cindy was “at her lowest,” Carly asked her mother if she wanted to hear a poem she had written.

As she listened, Cindy wrote in her memoir, she “was transformed from an ordinary human being into a crusader.”

Have you ever heard the sound of a mother screaming for her son?

The torrential rains of a mother’s weeping will never be done.

They call him a hero, you should be glad that he’s one, but,

Have you ever heard the sound of a mother screaming for her son?

::

It is a sacred duty to notify the next of kin when an active member of the military is killed. In the U.S. Marine Corps, the men and women who deliver the somber news are called Casualty Assistance Calls Officers. They try to knock on survivors’ doors within eight hours of learning that a Marine has died.

They arrived on Easter Sunday in 2004, the day 1st Lt. Oscar Jimenez, 34, was shot to death by insurgents in Iraq. Their first stop was the Twentynine Palms home where his wife and three children lived. Next was his mother’s place in San Diego. And, finally, his father’s house in Seattle.

Recounting one especially bad month in the wars following the Sept. 11 attacks.

Vanessa Jimenez, who was 15 when her father died, described how Marines in dark uniforms arrived to deliver the news April 11, 2004, in a poem she wrote not long afterward:

I asked why they were here

and Mommy said, “God has taken Daddy away”

Our big family misses you very much, especially Mommy

But don’t worry,

I will do my best to take care of her

just like you said on the phone.

Vanessa’s poem was included in her father’s Los Angeles Times obituary. He was the 10th Californian to die that month. Twelve more would follow.

Seventeen years later, she and her mother, Alejandrina Jimenez, could not be reached for comment. Sonia Jimenez, Oscar’s sister, is not surprised. She has not seen her sister-in-law, her niece or her two nephews since 2005. She has searched for them to no avail. This extra layer of loss, she said, breaks her heart.

The last time Sonia and Alejandrina spoke, Sonia said, was beside Oscar’s grave at Greenwood Memorial Park in San Diego, where he was buried with full military honors.

“She was grieving, and I’m sure she is still grieving,” Sonia said in a recent interview in San Diego, where she lives with her mother, Maria Noriega. “She said she needed her space, that it was really hard for her, which I totally understand.”

Sonia promised her brother’s widow that the family would respect her wishes. But she had one request: “When you’re ready, please don’t hesitate to call us, text us. Whatever you need, we’re here for you.”

They never heard from her again.

Oscar, Sonia said, was “the glue that held the family together.” Her children’s father was rarely around, but Oscar was always there for her. He was the one she’d call when her son wouldn’t do his homework or balked at doing his chores.

The one who made their extended family laugh. Who would sleep in his clothes as a high school student, because he was always late for class. Who loved Thanksgiving turkey and would give little kids some unauthorized help during family Easter egg hunts. Who brightened any room he walked into.

Since Oscar died, Sonia said, her mother’s health has deteriorated. Noriega, a former housecleaner, was treated for depression and diagnosed with diabetes. She is going blind and has not been able to work.

“The family has never been the same without” Oscar, Sonia said. “That’s for sure. My dad has never recovered. I don’t think he’ll ever recover. He has these random episodes where, again, he shuts everybody out of his life because he misses —”

Her voice trailed off.

Sonia’s living room is hung with pictures of her brother. She keeps a photograph of him in her car, visits his grave several times a year.

Sometimes, around Father’s Day or his January birthday, she’ll find a bouquet of big, red flowers near his headstone. Alejandrina, she knows, has been there first.

Sonia hops in her car. She circles the cemetery in search of the elusive woman her brother loved.

She circles. She searches. She hopes.

Times data and graphics editor Ben Welsh contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.