Anti-vaccine forces pushing ivermectin. It can be toxic, dangerous, officials say

Don’t take ivermectin, a drug used to treat parasitic infections, to prevent or treat COVID-19, health officials warn.

For months, ivermectin has become touted by people opposed to the COVID-19 vaccine as a way to prevent or treat COVID-19, despite the lack of scientific evidence the drug has any effect on preventing the disease. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved ivermectin to prevent or treat COVID-19.

Poison control centers nationwide said there was a threefold increase in calls related to exposure to ivermectin in January compared to the pre-pandemic period, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As of July, “ivermectin calls have continued to sharply increase, to a fivefold increase” from the time before the pandemic, the CDC said.

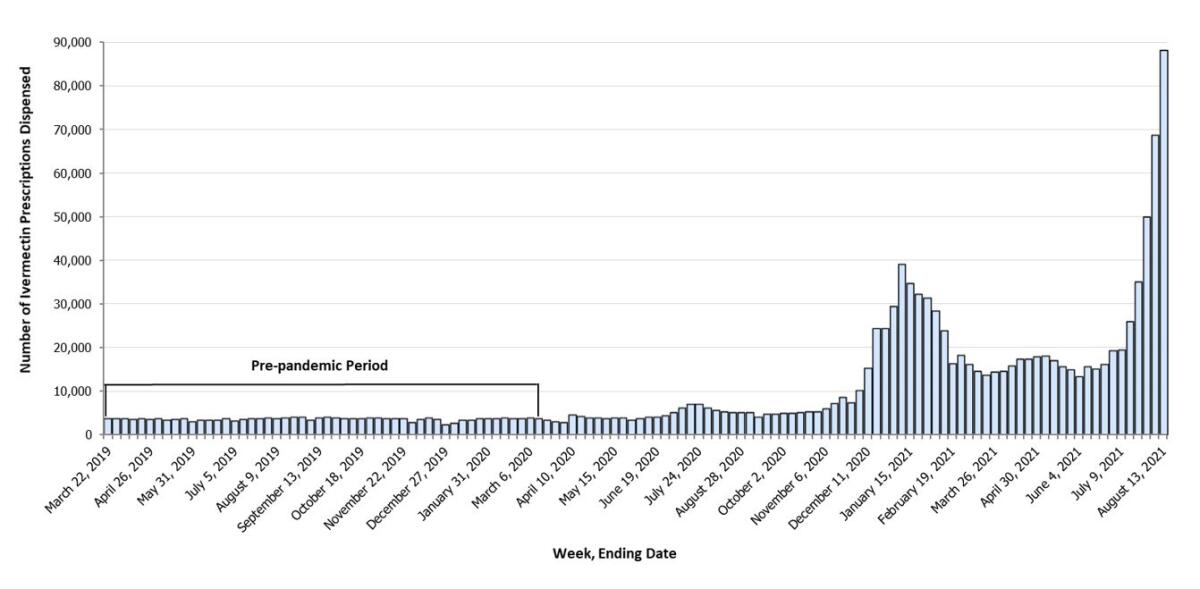

Before the pandemic, outpatient retail pharmacies nationwide dispensed 3,600 prescriptions for ivermectin a week. By early August, pharmacies were dispensing more than 88,000 prescriptions for the drug a week, representing a 24-fold increase, the CDC said.

“In some cases, people have ingested ivermectin-containing products purchased without a prescription, including topical formulations and veterinary products,” including those intended for use in large animals such as horses, sheep and cattle, which “can be highly concentrated and result in overdoses when used by humans,” a CDC health advisory said.

“People who take inappropriately high doses of ivermectin above FDA-recommended dosing may experience toxic effects,” the CDC warned. There’s also been increased reports of emergency room and hospital visits related to ivermectin overdoses.

Ivermectin, touted as a treatment of COVID by the anti-vaccine crowd, has “no effect,” according to a major study.

Dr. Clayton Chau, the Orange County Health Care Agency director and health officer, recently urged people not to ingest ivermectin that is manufactured for use as a lotion for topical treatments, such as to treat head lice in humans.

“Do not swallow ivermectin products that should be used on skin,” Chau said, nor should people consume ivermectin products intended for use on animals.

Symptoms of ivermectin poisoning include vomiting, nausea and seizures, Chau said.

Overdoses are also associated with low blood pressure, decreased consciousness, confusion, hallucinations, seizures, coma and death, the CDC said.

One adult recently drank an injectable version of ivermectin intended for use in cattle, thinking it would prevent a coronavirus infection, the CDC said, and suffered from confusion, drowsiness, visual hallucination, tremors and rapid breathing. The patient required hospitalization for nine days.

Another adult had to be hospitalized after taking five tablets a day of ivermectin — of unknown strength — for five days. The adult, who was disoriented and had difficulty answering questions, was hospitalized. The individual recovered after hospitalization.

Anyone experiencing symptoms of ivermectin overdose should promptly seek medical attention or call the poison control hotline at (800) 222-1222 for medical advice.

Besides veterinary use, ivermectin is FDA-approved for humans in oral formulations to treat diseases caused by parasitic worms; “river blindness,” a disease caused by a worm transmitted through the bites of blackflies, transmitted in Africa and South America; and intestinal strongyloidiasis, in which a roundworm parasite has infected the body.

Ivermectin produced for topical treatments can be used to treat head lice and rosacea, a skin condition.

As with chloroquine, there’s no reliable evidence that ivermectin works against COVID-19. You can’t censor what doesn’t exist.

Ivermectin is not a drug that treats viruses, the FDA said in an advisory in March.

“Taking large doses of this drug is dangerous and can cause serious harm,” the FDA said. “Never use medications intended for animals on yourself. Ivermectin preparations for animals are very different from those approved for humans. ...

“Animal drugs are often highly concentrated because they are used for large animals like horses and cows, which can weigh a lot more than we do — a ton or more. Such high doses can be highly toxic in humans,” the FDA said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.