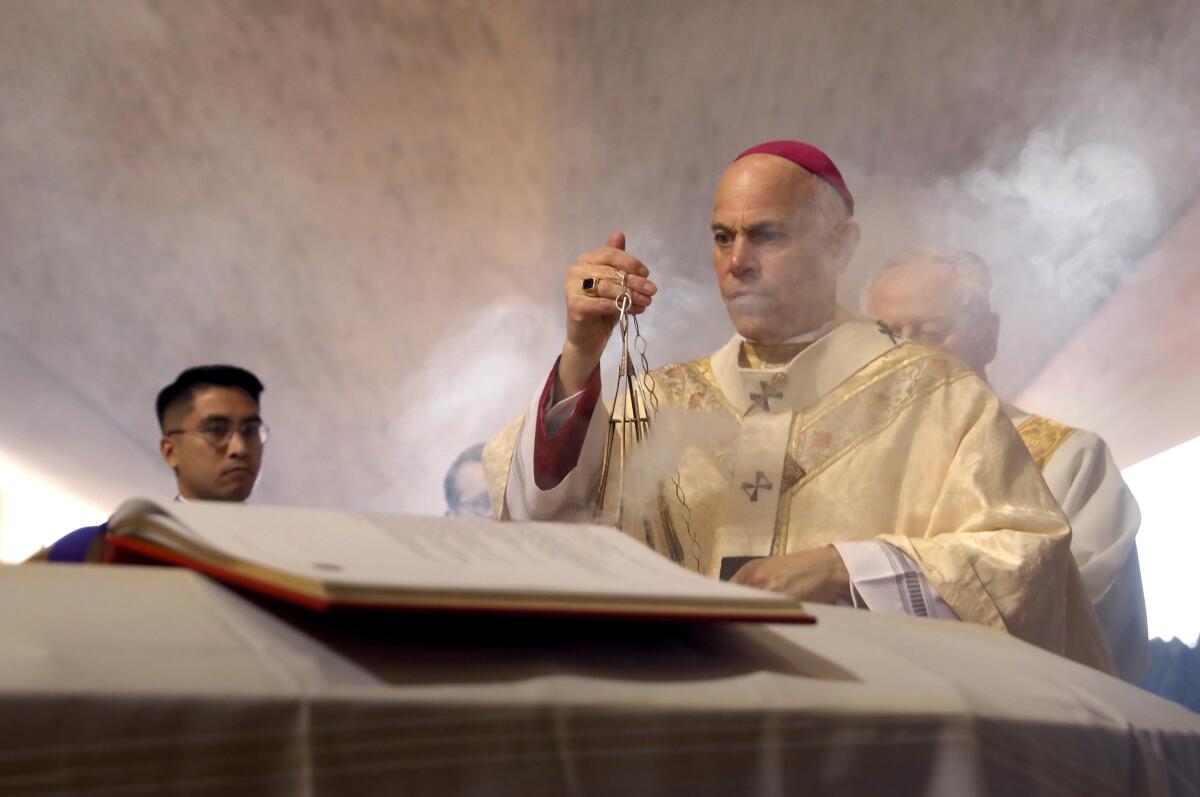

Decrying ‘evil’ of abortion, L.A. archbishop became public face of plan that could deny Biden Communion

“Brothers,” Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gómez addressed his colleagues, “before we come to the end of our meeting, I have an announcement to make.”

It was the middle of November, two weeks after Joseph R. Biden Jr. was elected president, marking only the second time that a Roman Catholic was headed to the White House. And the U.S. Conference of Catholic bishops had gathered virtually for a meeting amid a growing push by conservative bishops to withhold one of Christianity’s holiest rites from the man about to occupy the Oval Office.

“This presents certain opportunities,” Gómez, in his usual soft tone, said of Biden’s election, “but also certain challenges.”

Gómez, the group’s leader, told the bishops at the November meeting that Biden had given them reason to believe he’d support what the archbishop characterized as “good policies” on immigration reform and climate change, and against racism and the death penalty.

But the incoming president also had voiced support for what Gómez has described as “certain policies that would advance moral evils,” chief among them “the continued injustice of abortion” — a scenario that Gómez said could sow “confusion with the faithful about what the church actually teaches.”

So, after getting input from many fellow leaders, Gómez, a skilled conciliator, announced that he’d decided to launch a working group to examine the issue.

“This is a difficult and complex situation,” Gómez told the gathering, according to a recording of the meeting posted on YouTube.

In the months that have followed, the depth of that complexity has become abundantly clear, revealing sharp disagreements among the bishops themselves and laying bare deeper concerns about the future of the church amid a continued slump in attendance among U.S. Catholics.

Tensions rose higher leading up to the bishops’ June meeting, when they overwhelmingly approved a controversial plan to draft a teaching document that could lay the groundwork for denying the sacrament of the Eucharist, also known as the Holy Communion, to Biden, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other Catholic politicians who support abortion rights. The head of the bishops’ doctrine committee, which is drafting the still-unfinished document, has repeatedly stressed that the statement isn’t intended to be directed toward any specific Catholic or about any one issue.

Although the bishops’ actions have drawn support from conservative Catholics and anti-abortion activists, they have deeply disturbed some lay Catholics, as well as a faction of bishops who have argued that the step could weaponize the Eucharist and alienate many members of their flocks.

As president of the bishops conference and leader of the nation’s largest archdiocese, Gómez — who through representatives declined one request to be interviewed for this story, and failed to directly respond to two other such requests — has found himself at the center of a bitter dispute at the intersection of faith and politics.

“I don’t envy his job,” said Father David Garcia, who often interacted with Gómez in San Antonio, where he was archbishop before moving to Los Angeles. “He’s in a tough position.”

The Vatican weighed in on the fray through Pope Francis’ top doctrinal official, who in a May 7 letter warned the U.S. bishops that their actions could spawn “discord rather than unity.” The timing of the bishops’ pending statement — they are expected to vote on whether to approve the draft as early as November — could further strain the certain-to-be-fractious 2022 midterm election.

Despite the church’s long-standing public opposition to abortion, more than half of U.S. Catholics — 56% — say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to a Pew Research Center poll. Another Pew poll found that 67% of U.S. Catholics asked about Biden’s views on abortion said they thought the president should be allowed to receive Communion.

Mary Ziegler, a professor of law at Florida State University and author of “Abortion and the Law in America: Roe v. Wade to the Present,” said that in recent years many Catholic leaders have taken a don’t-ask-don’t-tell approach on abortion. They haven’t publicly wavered in their opposition, she said, but there appeared to be an understanding, especially in progressive cities like Los Angeles, that at least some of their parishioners don’t share the leadership’s more restrictive views.

“It’s a question of, do you try to have a bigger, more diverse community at the expense of some doctrinal purity?” she said, adding that, given the church’s long public stance on the topic, she doubts that the bishops’ step will change many rank-and-file Catholics’ views on abortion.

“In some ways it’s old news,” Ziegler said. “It’s Bishop Gómez trying to drive home a point that’s been true for a while.”

::

His extremely public role as point man on the issue is in some ways unusual for Gómez, who’s generally been a less visible public presence than his voluble predecessor, Cardinal Roger Mahony, whom he succeeded in 2011.

The son of a homemaker and a physician, Gómez grew up in Monterrey, Mexico, where he served as an altar boy — an early indication of his lifelong passion for his faith, which years later took him to Spain, where he earned a doctorate in theology, before moving to the United States to minister.

Through the years — during leadership stints in Denver, San Antonio and now Los Angeles — Gómez, the first Latino to lead the bishops’ conference, has established himself as a quiet but powerful figure. He isn’t fiery and doesn’t often speak in as overtly political terms as many of his counterparts.

But Gómez has long exerted his influence on issues he feels passionately about, including immigration and abortion.

Father Garcia said the archbishop’s leadership style was often guided by his focus on upholding church doctrine. During his first year as archbishop of San Antonio, Gómez remained largely in observer mode, Garcia recalled, but when he eventually started suggesting things he thought should be done differently, he always came prepared with documentation.

“It wasn’t just his personal preference,” Garcia said. “It was, ‘Here is what the church tells us to do liturgically.’ He preferred us to stick by the book.”

And yet, Garcia said, Gómez is far from inflexible.

“A lot of people have this idea about him that he’s just super conservative and very rigid. My experience? Yes, conservative. Yes, by the book. But not rigid. I found him willing to talk, willing to listen,” said Garcia, who added that, above all, he’s been extremely grateful for Gómez’s strong leadership in advocating for rights and compassion for immigrants.

In 2005, Time magazine named Gómez one of the most influential Latinos in the nation, saying his views on immigration held sway in Rome and within the federal government. In the years that followed, Gómez, who became a U.S. citizen in 1995, has preached and written extensively on the topic.

“In my opinion, immigration is the human rights test of our generation,” he told Crux, a news service covering the Catholic Church, in 2017, for a piece that examined how Gómez didn’t fit neatly into the simple, often reductionist, labels of leaders as either liberal or conservative.

Gómez also has commented extensively on abortion.

In 2008, four years into his time as archbishop of San Antonio, he publicly criticized a local Catholic university for inviting then-presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton to campus, citing her support of abortion rights. Later that year, he wrote a column calling abortion the foundational issue of our time and expressing displeasure with Catholic politicians who he felt had made misleading statements on the topic. He mentioned only one politician by name: Biden, then a senator.

In a statement issued on Biden’s Inauguration Day, Gómez said he was praying for the new president, whose piety and personal story he found hopeful and inspiring. And yet, as a pastor, Gómez wrote, he had an obligation to proclaim truths even when they are inconvenient.

In the months that followed, two other leading California Catholics — San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone and San Diego Bishop Robert McElroy — waded in on opposite sides of the increasingly divided public conversation.

In early May, Cordileone, known for his willingness to push hot-button cultural issues, including his role as a key player in the passage of Proposition 8 — the 2008 anti-gay-marriage California ballot measure — released a 17-page pastoral letter on abortion, Communion and Catholics in public life. In the letter, he argues that in situations in which a Catholic leader persistently supports abortion rights it is appropriate for his or her priest or bishop to temporarily exclude them from receiving Holy Communion.

“This is a bitter medicine, but the gravity of the evil of abortion can sometimes warrant it,” Cordileone wrote in the letter, which didn’t single out anyone by name, but was interpreted by many observers to possibly carry hefty implications for one of his parishioners, Pelosi, who supports abortion rights.

Four days later, McElroy published a piece in the Jesuit magazine America under the headline, “The Eucharist is being weaponized for political ends. This must not happen.”

Any national policy of excluding pro-abortion-rights political leaders from the Eucharist would erode unity within the church, McElroy wrote, adding that many Catholics would no doubt see the move as deeply partisan. He also took issue with what he saw as applying sanctions selectively and inconsistently — focused largely, as he saw it, around the issue of abortion and, at times, euthanasia.

“Why hasn’t racism been included in the call for eucharistic sanctions against political leaders?” wrote McElroy, who through a spokesman declined a request to discuss the topic in greater detail.

In an interview with The Times last month, Cordileone stressed that while he and other bishops take several issues very seriously, including immigration and racism, he views abortion as in a “category all by itself.”

“This is the greatest human rights issue of our day,” he said, bristling when asked about figures showing that a majority of Catholics support abortion. “Polls do not dictate what’s right and what’s wrong.”

While there is, indeed, a camp of leadership who argue that it’s wiser to keep people in the door and continue to edify them, Cordileone is not among them.

“Seems to me we’ve been trying that approach for the last 50 years and it hasn’t been working,” he said.

Asked about Gómez’s leadership style in recent months, Cordileone credited him for navigating “all kinds of pressures” without getting rhetorical or taking sides.

“I think he steered a very even-keeled course on this.”

::

In his letter to the American bishops — whom Pope Francis has publicly admonished before — the pope’s top doctrinal officer, Cardinal Luis Ladaria, urged them to have “extensive and serene dialogue” on the topic and warned that it would be misleading to draft a statement that gave the impression that abortion and euthanasia alone were the issues that demand the fullest accountability.

During public comments at the virtual meeting in June, several bishops spoke passionately about why they intended to vote against the proposal, often saying they feared it would continue to disrupt unity and get mired in partisan strife.

“Such a path will be profoundly alienating for immense numbers of the faithful,” said Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, N.J.

Bishop Robert Coerver of Lubbock, Texas, questioned the speed at which the process of voting on whether to draft a document appeared to be unfolding.

“I can’t help but wonder if the years 2022 and 2024 might be part of the rush,” he said.

The bishops, who cast their votes privately, ultimately approved the proposal by a wide margin.

Soon after the vote was made public, Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) tweeted at the bishops conference, saying he was a Catholic who supports both contraception and a woman’s right to choose.

“Next time I go to Church,” he tweeted, “I dare you to deny me Communion.”

Similar comments soon began popping up in the replies on Gómez’s Twitter feed.

“Looks like I’ll be leaving again,” wrote a man who said he’d recently returned to the church.

But others praised Gómez, including someone who tweeted, “In the face of opposition thank you for not bowing to the pressure!”

Among the archbishop’s supporters is Frida Plata, a high school senior in Cypress and a devout Catholic.

“I’m pretty proud of him,” she said. “I’m really in awe.”

Plata remembers feeling bowled over by the power of God’s love several years ago while attending classes in preparation for her Holy Communion. These days her faith often shapes her conversations — she sometimes chats up her public school teachers about her favorite saints or debates with friends about abortion.

Plata said she was especially pleased with Gómez’s Inauguration Day statement referring to “moral evils,” adding that she would be happy if he spoke publicly about abortion even more often.

She is deeply inspired by Father Frank Pavone, an outspoken opponent of abortion rights, who lent fierce, controversial support to former President Trump, whom Plata said she intends to vote for if he ever runs again.

“He is really strong in defending the unborn,” she said, adding that many members of her Mexican American family are big fans of Trump, in large part because of his stance on abortion.

But for other Catholics, like Sara Ortega Roliz, the recent steps by the bishops conference felt like a disappointing, exclusionary step.

“I feel like it’s the church’s role, especially while it’s bleeding membership, to open its arms and welcome people in and rebuild itself,” said Ortega Roliz, 40, who grew up in Los Angeles attending Catholic schools and now runs a coffee roasting business with her husband in San Francisco.

“As society becomes more progressive, but the church isn’t willing to hear that side of the story, they’re essentially becoming that grumpy old man in the corner kicking dirt,” she said.

On a recent weekday, Rameses Arce sat among 50 or so other worshipers distanced from one another during the midday Mass at the Cathedral of our Lady of the Angels in downtown Los Angeles.

Arce, a 50-year-old hairdresser who lives in Rancho Cucamonga, said he has universalist faith views, but was born into the Catholic faith and still considers it his “main base.”

The bishops’ move seemed well within their rights, he said, comparing it to a parent disciplining a child. He saw how the church leaders could frame the move as saying, “We’re not taking Christ away from you. You’ve turned away from Christ.”

And yet, he said, such a decision needed to be handled with great sensitivity.

“It does sound bad,” he said. “‘We have to take away Communion from you.’ It sounds horrible.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.