L.A.’s quiet archbishop has a message for immigrants, and prayers for president-elect Trump

The archbishop spoke with a patience that belied his frustration.

“My dear brothers and sisters,” he said to the congregation that had gathered at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels on the Thursday evening after the presidential election. “We are here tonight because our people are hurting, and they feel afraid.”

For more than 10 years, Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez has argued that the U.S. immigration system is broken, and now overnight, the terms of the debate had shifted.

The calls for a massive increase in deportations, the political rhetoric of the last year, threatened to become reality, and as he looked out upon the faces of the faithful, he could see their anxiety.

We pray for our leaders, including our President-elect

— Archbishop Jose Gomez

That afternoon, with preparations in place, he had retreated to his private chapel and prayed. Most homilies take days to prepare, and he had a little more than an hour to find the words to ease the fear sweeping through the archdiocese.

He was nervous. Like most everyone, the result of the election had surprised him. What was he supposed to say?

After a year of insults, threats and bombast, the election had laid bare the vulnerability of the governed.

His quiet, amplified voice echoed through the cavernous space as he continued. “We are here to listen to their voices because they feel they are being forgotten.”

The prayer service had been organized at the last minute, inspired in part by a phone call from L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office, and only 100 or so congregants were in attendance. Garcetti spoke, as did leaders representing the Jewish, Muslim and Christian faiths.

But for Gomez, who came to this country from Mexico, the service was an opportunity to show the church’s solidarity with the more than 3 million Latinos in the archdiocese.

“That’s what tonight is about,” he said. “Not politics. It’s about people.”

The words had a personal meaning for Gomez, whose mother’s family was from San Antonio and whose father’s family came from Monterrey, Mexico, where he was born.

As a child, he crossed the bridge at Reynosa, Mexico-McAllen, Texas, to visit his mother’s family during the summer and spring break. His father liked to fish, and they would go to Padre Island in Texas. Even though he had a passport and a tourist visa, “la mica,” he recalls how scary the border crossing was.

“Right now — all across this city and in cities all across this country — there are children who are going to bed scared,” he said.

From 2009 to 2015, more than 2.5 million people had been deported under the Obama administration. Now it appeared that many more were at risk.

In the United States, there are 11.3 million undocumented immigrants, including the almost 750,000 so-called Dreamers, who had been given protection under the federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

The president-elect has promised in the next two years to either pressure them to leave or deport them, which would mean taking 15,000 into custody every day.

“There are men and women who can’t sleep because they are trying to figure out what to do … when the government comes to take them away from their kids and their loved ones,” Gomez said, mindful of families divided, of the children who’ve lost parents, of grandparents disappearing from their lives.

He has long argued that economic desperation drives families to give up their homes and come to the United States. It is what makes Americans unique: not just their citizens’ immigrant past but their acceptance of newcomers. Immigration, he has written, is not a problem but an opportunity to renew the values that founded this country.

After years of pastoral work in Mexico, he was assigned to a parish in San Antonio in 1987. He was ambivalent about going. He describes his ministry in Monterrey as beautiful. At first he applied for an R-1 visa for religious workers, and within six months, he had a permanent resident card, a green card.

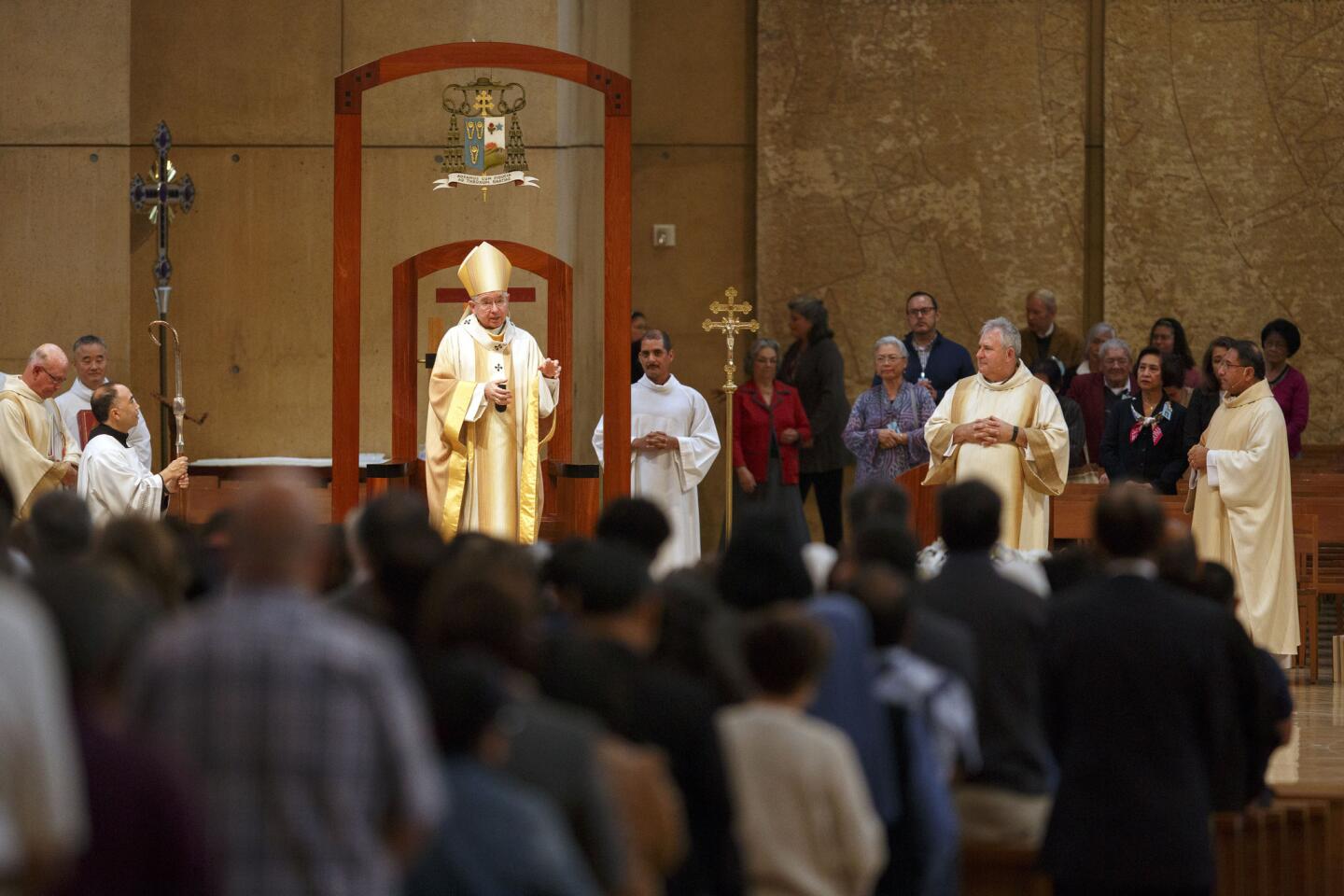

At the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in downtown Los Angeles, Archbishop Jose H. Gomez, along with Rabbi Sharon Brous; Salam Al-Marayati, executive director of the Muslim Public Affairs Council; and the Rev. Najuma Smith-Pollard participate in

In 1995, Gomez became a citizen, inspired, he says, by the chance to make a contribution to the United States.

He says that many immigrants want to do the same. When he thinks about what it means to be an American, he says he thinks about his mother and her respect for others, her willingness to listen.

But in the succeeding years he has watched the generosity of this country grow scarce, he says, reflecting upon the words of Pope Francis who has spoken about “the culture of selfishness and individualism” in society.

In 2011, Gomez testified before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement and outlined the position of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in their opposition of workplace immigration raids and in favor of reform.

Two years later, he represented the bishops’ position before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

That same year he put his thoughts in a short book, “Immigration and the Next America: Renewing the Soul of Our Nation.”

NEWSLETTER: Get essential California headlines delivered daily »

At the time there was the hope that politicians in Washington would fix the system.

“My fear,” he wrote, “is that in our frustration and anger, we are losing our grip and perspective…. I’m worried we are losing something of our national soul.”

His homily echoed this idea but with added urgency.

“We are better people than this,” he said. “We should not accept that this is the best we can hope for — in our politics or in ourselves.”

Carolina Guevara, a spokeswoman for the archdiocese, said she is moved by the passion in the archbishop’s words. She also discerned a feeling of loss, a sense that all the progress advocating for a humane immigration system might be swept away.

The night before the service, demonstrators burned an effigy of President-elect Donald Trump’s head in front of City Hall. Some spray-painted graffiti denouncing the president-elect on buildings and sidewalks, and hundreds stormed onto the 101 Freeway north of downtown, shutting down traffic.

That day, Gomez had tweeted: “True civility means demonstrating real respect for other people, even if we are deeply opposed to their positions or even their worldview.”

Speaking in the cathedral, he needed to be more direct. “The answer is not angry words or violence in the streets,” he said. “It never solves anything; it only inflames things more.”

Yet he understood frustration. He has lived with it through three administrations and doesn’t understand why politicians — against the wishes of their constituents — have been unable to fix the immigration system. It seems to him that they don’t want to.

“Tonight,” he said, “we promise our brothers and sisters who are undocumented, we will never leave you alone. En las buenas y en las malas. In good times and in bad, we are with you. You are family.”

When Ellie Hidalgo of the Dolores Mission heard the words — en las buenas y en las malas, a popular idiom expressing the unbreakable bond, the love within a family — she let out her breath.

She had come to the cathedral with nearly 30 members of her Boyle Heights parish, families who wanted to know what the archbishop would say at such a precarious time. She now felt inspired.

Let’s pray that they can come together, in a spirit of national unity, and agree to stop the threat of deportations — until we can fix our broken immigration

— Archbishop Jose Gomez

“Also tonight — as we come together to pray for unity and to ‘bind the wounds of division’,” said Gomez, borrowing a phrase from the president-elect’s election speech, “we pray for our leaders, including our president-elect.”

“Let’s pray that they can come together, in a spirit of national unity, and agree to stop the threat of deportations — until we can fix our broken immigration system.”

Gomez has never argued for a complete amnesty. He has said that those who are here illegally must be held accountable with fines, maybe community service, and educate themselves about the country’s laws and government. Deportation, he believes, is a punishment that doesn’t fit the crime.

And in the final words of his homily, he called upon the archdiocese’s most enduring symbol of hope and unification, a symbol of faith that endures across borders in times of peril.

“And may Our Lady of Guadalupe — the Mother of Jesus and the Mother of all the peoples of the Americas — may she watch over us and help us to truly become one nation under God.”

ALSO

San Diego judge who mediated Trump University case praised as ‘steady hand’

Border Patrol union welcomes Trump’s proposed wall as a ‘vital tool’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.