A place to sleep, party and kill: Abandoned L.A. buildings become MS-13 gang ‘destroyers’

It looked like just another tired apartment building on Rampart Boulevard.

Emptied of its tenants so a development company could pursue plans to knock the place down and put up a high-rise, the building’s windows were smashed out of their frames and its doors pulled off their hinges. Thieves stripped the place of its fixtures.

Then a group of teenagers and young men slipped inside. They announced their illicit occupancy in white spray paint on the green canvas stretched across a chain-link fence that had been put up: “MS CLCS.”

They were from the Coronado Lil’ Cycos clique of Mara Salvatrucha, the gang widely known as MS-13, and they had turned the abandoned building into a place to sleep, party, host meetings, peddle drugs — “clandestine things they don’t want to hold out in the open,” a Los Angeles police detective explained in court.

The gang has a name for places like this. The building had become a “destroyer.”

The destroyer on Rampart was also a place to kill. Three people were slain within its blighted rooms in 2017 and 2018, detectives testified at a hearing last month in the case of two alleged MS-13 members charged with the murders. Authorities suspect a fourth victim was lured to the building, then driven to the mountains above Los Angeles and stabbed to death.

There is no count of how many destroyers pockmark the city on a given day. Several have been found in the Los Angeles neighborhoods that MS-13 considers its turf — Westlake, Pico-Union, parts of Koreatown and East Hollywood — where the churn of gentrification and neglect from absentee owners give rise to a crop of buildings abandoned or marked for demolition. Hollowed out, they invite members of the gang to make the squalid interiors their own — for a time at least.

Destroyers reflect the wretchedness of daily life in a gang made up largely of poor young men and teenagers, who commonly are homeless or estranged from family. They subsist on petty drug dealing, theft and extortion of innocent street vendors and minor criminals lower on the underworld food chain than themselves. A paranoid, often misplaced, belief that their ranks are seeded with police informants runs deep in the gang, leading members to turn on each other.

The lives cut short inside the destroyer on Rampart were marked by poverty and fractured families — not unlike the lives of their alleged killers. One was both victim and perpetrator: An MS-13 member who took part in the killing of a teenager inside the destroyer was himself beaten to death days later in the same building.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Outside its doors, life tumbled along in Rampart Village, a densely packed Los Angeles neighborhood in the heart of MS-13 territory. Every day, countless people walked and rode past the destroyer, oblivious to its secrets.

On a recent afternoon, two women hawked bags of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos and bunches of browning bananas beneath a canopy on Rampart’s sidewalk. Old men played cards outside an apartment complex in a neatly tended garden full of flowering plants. Children chased one another on the sliver of grass between sidewalk and street.

They were never more than a few steps away from spray-painted reminders of MS-13’s presence. Scrawled on sidewalks, electrical boxes, trees, facades of buildings are the letters “MS X3 CLCS RLS” — shorthand for the Coronado Lil’ Cycos and the neighborhood’s other MS-13 clique, the Rampart Locos.

::

The morning of April 18, 2019, Francisco Madrid was locked up in the basement jail at the Los Angeles Police Department’s 77th Street station in South Los Angeles.

Police suspected Madrid of killing three people whose bound and stabbed bodies had been found in the Angeles National Forest, Elysian Park and South Los Angeles.

Believing his cellmate also belonged to a gang, Madrid, 22, introduced himself as “Lil’ Serio” from MS-13’s Coronado clique, testified Det. Frank Flores of the LAPD. In fact, the man was a paid informant, Flores said, and the cell had been outfitted with secret recording devices.

Detectives listened as Madrid told his cellmate about Raylynn Josephine Deanne Hernandez, who as a teenager had run away from her San Bernardino home and ended up in L.A., where she fell in with Madrid’s Coronado clique, according to Flores’ testimony.

Hernandez had run-ins with police and struggled to support herself. When she was arrested for car theft, she gave police a home address in South L.A., but during one of several arrests for robbery she said she was transient, jail booking records show. She is listed in jail records as a “cleaning lady” or as unemployed.

Madrid told his cellmate that he and others suspected Hernandez, who was 21 at the time, of being friendly with members of 18th Street, MS-13’s bitter rival. Some in the gang worried she had spotted them with a member of 18th Street who later went missing and is believed to have been killed, Flores testified.

Believing Hernandez was a “rat,” Madrid told his cellmate that he and other Coronado members beat her to death with a bat in the Rampart destroyer and then rolled up her body in a piece of carpet, Flores said. Madrid claimed others in the gang removed her body from the building, the detective said.

A motorist was driving along Angeles Crest Highway on Christmas Eve 2017, when he spotted a trail of blood leading off the side of the road. Thinking an animal might have been hit by a car, he pulled over and peered down an embankment. Hernandez’s body was about 10 feet down the mountainside.

Her ankles, wrists and mouth were bound with duct tape. She had been stabbed, struck in the head with a heavy edged weapon, strangled with a ligature and beaten, according to a coroner’s report.

Madrid and his codefendant, Kevin Mejia, have pleaded not guilty to three counts of murder. Mejia was also recorded discussing several killings with a cellmate he believed to be a gang member, detectives testified.

Attorneys for both defendants disputed the accuracy and legitimacy of the recorded statements obtained during the jailhouse sting.

A federal indictment detailing killings by the MS-13 gang’s Fulton clique shows the Central American gang’s bloody tactics could be escalating in the Valley.

::

Destroyers are more than a backdrop to macabre crimes. They reflect the reality that MS-13, for all its violence and fearsome reputation, is made up of mostly poor teenagers and young men whose ties to family are often tenuous or untethered altogether.

MS-13 members commonly come to the United States from Central America as unaccompanied minors with few, if any, relatives in Los Angeles. They often live hand to mouth, scraping out a living peddling drugs and using threats of violence to shake down street vendors and low-level criminals in neighborhoods the gang considers its turf.

Often they have no home. Many are living in “tent cities” in and around Westlake’s MacArthur Park, an LAPD detective recently wrote in seeking a warrant to search the tent of a suspected juvenile MS-13 member on 6th Street.

Other members exist on the periphery of homelessness, said Steven Dudley, author of the recent book, “MS-13: The Making of America’s Most Notorious Gang.” It is “a little-understood portion of gang life,” he said, that runaways, outcasts seeking escape from abusive homes or young men who left behind family to come to the United States can end up at a destroyer, Dudley said.

More than just a place to sleep, they are social hubs where MS-13 members find company and operate “mini-criminal economies”: reselling stolen goods, pushing drugs, running prostitutes, storing weapons, hiding from police, according to Dudley.

“Literally, their name comes from the fact that over time, their activities would lead to the destruction of the property,” he said. “And that name stuck.”

It stuck hard enough, in fact, that MS-13 members, who primarily speak Spanish with each other, still call the buildings destroyers, Dudley added.

::

Miguel Sanchez and Christopher Bernal followed similar paths to the destroyer on Rampart — the place where one would help kill the other and then be killed himself.

Bernal, 22, was a Salvadoran immigrant with no known family in the United States. Arrested near MacArthur Park in 2016, he told the police he was homeless and worked as a “clean sweep,” according to booking records.

To his MS-13 clique, he was known as “Big Killer” and “Maleante,” police testified. Tattooed on his chest were the words: La memoria de los muertos en la mente de los vivos. The memory of the dead in the minds of the living.

At 14, Sanchez left his hometown of Soyapango on the outskirts of the Salvadoran capital, San Salvador. He journeyed north, crossed into the United States with the help of a smuggler and settled in Los Angeles. As a student at Edward R. Roybal Learning Center in Westlake, he began hanging around gang members.

Officer Daniel Cardenas, who works a gang detail in the LAPD’s Rampart Division, testified that Sanchez had told him he was a member of the Coronado clique. The teenager had once lifted his shirt to show Cardenas the tattoo that covered his back. Inked from shoulder to shoulder was a skeletal hand clenched in the gang’s sign: thumb, middle and ring finger joined, index and pinky fingers extended. The sign of the devil, Cardenas explained.

Inside the destroyer, Madrid, Bernal and others in the gang accused Sanchez of being a “PC,” a slang term for a police informant, which is short for protective custody — the special unit in jail that houses inmates who cooperate with law enforcement, Flores testified.

Sanchez had pleaded for mercy, Madrid told his cellmate, mimicking the noises the teen had allegedly made as he begged for his life, according to the detective. Madrid said after he, Bernal and the others killed him, Madrid had driven Sanchez’s car to South Los Angeles and ditched the vehicle with the body inside it, the detective testified.

Days later, the gang turned on Bernal. Detectives listened as Madrid recounted how he and others had confronted Bernal inside the destroyer, calling him a “peseta” — slang for someone who has cooperated with the police, Flores testified.

After killing Bernal, Madrid said they had loaded the body into Bernal’s car and dumped the corpse in Elysian Park near the LAPD’s training academy, pelting it with rocks before driving off, according to Flores. Madrid said he brought Bernal’s car to a mechanic and told him to clean the vehicle, then sell it, the detective said.

Bernal’s body was found the morning of Feb. 22, 2018, sprawled facedown on a hillside in Elysian Park. His wrists and his ankles were bound with shoelaces, and his red shorts were pulled down below his knees. His skull and cheekbones had been shattered and his teeth knocked out of his jaws, wounds consistent with being struck with a baseball bat, a deputy medical examiner testified.

The search for Sanchez, meanwhile, went on. His girlfriend had reported him missing, telling LAPD officers she had last seen him when he dropped her off at work in her white Honda Civic, according to a coroner’s report. He was supposed to have returned to pick her up.

Sanchez had tried to leave MS-13 after getting arrested a year earlier, the girlfriend reported, and she “feared that they may be responsible,” a coroner’s investigator wrote.

The morning of March 1, 2018, LAPD officers checked on a white Honda Civic in an alley near 83rd and Hoover streets in South Los Angeles. It was parked illegally, and a ticket was tucked beneath a windshield wiper.

They found Sanchez’s body in the trunk, wrapped in blankets. His skull was broken. He had been stabbed in the heart.

A trial provided details into the killing of 16-year-old Brayan Andino but could not explain what a prosecutor called “a culture of death.”

::

Authorities have found destroyers in buildings on James M. Wood Boulevard in Westlake, Mariposa Avenue in East Hollywood and Berendo Street in Koreatown.

The structures on Berendo Street — two dilapidated, century-old apartment buildings — are still standing. One, a clapboard building whose upper story was gutted by fire, appeared on a recent afternoon to still be inhabited, although it was unclear who was inside. Sheets of plywood nailed over the windows and doors were spray-painted with MS-13 graffiti. No tenants have lived there for at least four years, according to city planning records.

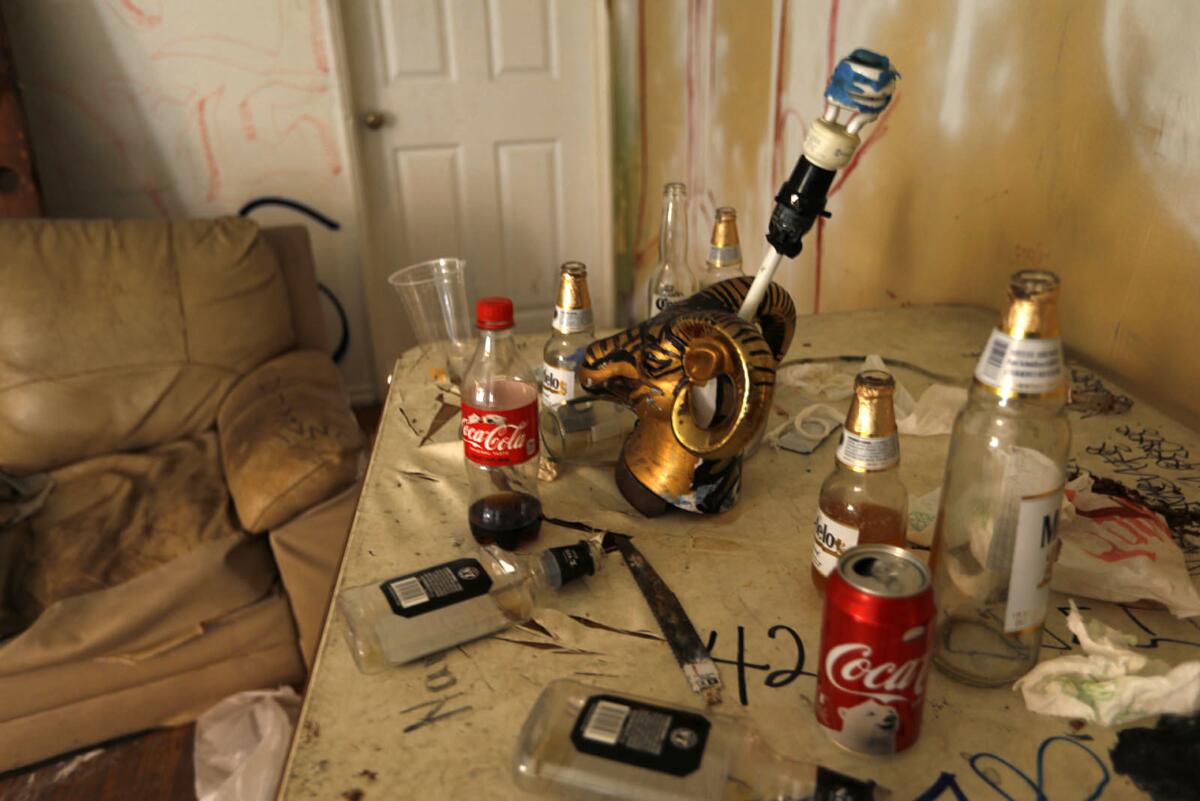

In 2019, a Times reporter gained entry to a destroyer in a deserted building near 8th and Irolo streets in Koreatown. Empty bottles of beer and liquor and an odd lighting fixture in the shape of a ram’s head were strewn on a table. Graffitied on a wall from floor to ceiling were the words: En Memoria Del Perro: In Memory of the Dog.

Today, all that remains of the destroyer where Hernandez, Bernal and Sanchez are said to have been killed is a vacant lot. It is overrun with weeds and a few scraggly trees, littered with empty cigarette packs and faded cardboard boxes of Modelo beer — a missing tooth in an otherwise unbroken row of large, bustling apartment buildings that line the wide boulevard.

The owners of the lot, a development company with offices in Wilshire Park, obtained the city’s approval to demolish the building in late 2017. In its place, they envision raising a six-story, 53-unit apartment complex with a rooftop deck.

Times staff writers Ruben Vives and Brittny Mejia contributed to this report.

Nelson “Mula” Flores, who authorities say is one of MS-13’s most influential members outside El Salvador, is taken into U.S. custody.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.