Suspected MS-13 leader’s capture offers window into gang’s structure

On May 20, in the border district of San Ysidro, Mexican authorities quietly turned over a 49-year-old member of MS-13 to the FBI.

The handoff of Nelson Alexander Flores came with none of the ceremony that typically accompanies the capture of MS-13 gang members. There was no photo-op, no press conference, nothing like the recent spectacle in the Oval Office, when President Trump and his attorney general announced they would seek the death penalty against an MS-13 member accused of killing two teenage girls with baseball bats and machetes and charge another with terrorism.

In driving a hard line against illegal immigration and crime in the country’s big cities, Trump has sought to cast MS-13 as his administration’s foil, a direct threat to the American public that has seeped out of Los Angeles and El Salvador and into the nation’s heartland. MS-13 is “an evil group of people,” Trump said in the Oval Office, “sick” and “deranged.” Atty. Gen. William Barr, standing alongside him, likened the gang to “a death cult.”

Yet Flores, known by the nickname Mula, has never been accused in any of the macabre slayings for which MS-13 has become known. Instead, law enforcement officials said in interviews, he filled a quieter, more essential role in the organization supplying MS-13 cells with narcotics, smuggling juvenile MS-13 recruits into the United States and sending money back to the gang’s leadership in El Salvador. The officials requested anonymity because they weren’t authorized to discuss investigations into Flores and his associates.

Crucially, the officials said, Flores serves as a liaison with the Mexican Mafia, the crime syndicate that acts as an arbiter in the Southern California underworld that MS-13 occupies. For these reasons, he is perhaps the gang’s most influential member outside of its leadership in El Salvador, the officials said.

Flores is under indictment in Ohio, charged with extortion and money laundering. He has yet to enter a plea. A lawyer who represented Flores during an initial appearance in San Diego federal court didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The Times traced Flores’ story, rising from an obscure MS-13 cell in Nevada to being groomed in prison by the Mexican Mafia to establishing and operating a base of operations in Tijuana, through a review of court records and interviews with law enforcement authorities.

Born in El Salvador, Flores was a child when the country descended into civil war. Two of his sisters were killed in terrorist attacks, and when Flores was 15, marauding fighters robbed the family’s home and shot his mother in the stomach, his attorney wrote in a sentencing memo.

He left El Salvador at 16 to live with his brother in Reno, where he joined a gang, his lawyer acknowledged in the memo. While she didn’t identify the gang by name, authorities said it was MS-13.

Founded in the 1980s in the dense, impoverished districts just west of downtown Los Angeles, MS-13 metastasized when the U.S. government deported much of its membership to El Salvador in the 1990s. The gang is now entrenched in the small Central American country, leeching its economy through extortion and driving up its homicide rate, which ranks among the highest in the world.

A faction within MS-13 used gruesome tactics to kill seven people in the L.A. area since 2017, prosecutors said.

In 2000, Flores himself was deported after serving a prison term in Nevada for a felony firearms conviction. He reentered the United States illegally and made his way to Columbus, Ohio, his attorney wrote in court papers.

Investigators in Columbus first noticed MS-13’s presence in the mid-2000s, an FBI agent wrote in support of a search warrant. Flores was a leader in an MS-13 clique in Columbus, a law enforcement official said. He and other alleged MS-13 figures shook down victims in Columbus, then wired “some, if not all” of the money to members and associates in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, according to an indictment and an FBI agent’s affidavit.

MS-13 leaders in Central America used the funds to buy weapons and support the families of gang members who had died or been incarcerated, the agent, Thomas J. Gill, wrote.

By appearances, however, Flores seemed a hard-working man with a new wife and a child on the way, according to a sentencing memo and letters submitted to a judge.

He juggled three legitimate jobs in Columbus, working for a painting company, a metalworking plant and a flooring contractor, who described Flores in a letter to the court as a “well-mannered, respectful and punctual employee.” Employed at the metalworking plant under the name David Aguilar and a fake Social Security number, he made $12 an hour and sent money to his ailing mother in El Salvador, according to his sentencing memo and payroll documents filed in court.

His double life fell apart in 2004, when he got in a minor traffic accident and told the Columbus police his name was Toni Pachecho, a federal agent wrote in an affidavit. The police learned his real name and found there was a warrant issued for his arrest, the affidavit said. He was turned over to immigration authorities, charged in federal court with illegally reentering the country and sent to prison for nearly six years.

Far from serving as a deterrent, those years in the federal Bureau of Prisons opened new vistas of criminal opportunity for Flores, who to this point was essentially a midlevel manager for a backwater chapter of MS-13, law enforcement officials said.

While incarcerated in Kentucky, Flores met a particularly influential member of the Mexican Mafia — Jose Landa-Rodriguez, a native of Michoacan and chieftain of the South Los street gang, one official said. Landa-Rodriguez, known as Fox Tapia, groomed Flores to work with the Mexican Mafia, the official said.

MS-13, like nearly every Latino street gang that operates in Southern California, answers to the Mexican Mafia. A syndicate of about 140 men, most of them incarcerated, the Mexican Mafia exacts “taxes” — its term for extortionate cuts of drug sales and other street-level crimes — from the gangs beneath its umbrella, including MS-13. In exchange, the Mexican Mafia offers protection in the jails, prisons and streets it controls.

After finishing his prison term, Flores was deported. By no later than 2014, he had made his way north to Tijuana, where he began working with Robert “Peanut Butter” Ruiz, a Mexican Mafia member and ally of Landa-Rodriguez, law enforcement officials said.

Investigators in L.A. caught a glimpse of Flores’ operation while probing a series of killings between 2013 and 2015. Their focus had narrowed on the Park View clique of MS-13, and they obtained court approval in 2015 to monitor the clique’s phone calls, court records show.

Investigators listened to conference calls between Park View members, MS-13 leaders in Salvadoran prisons and representatives of MS-13 chapters nationwide, including in Houston, Virginia, Fayetteville, Ark., and Mendota in California’s Central Valley, a law enforcement official said.

Authorities learned that Flores was smuggling juvenile MS-13 recruits and narcotics into the United States, three officials said. Flores was also overheard instructing the Park View clique to deliver rifles to Tijuana, which he intended to ship south to MS-13 fighters battling Salvadoran security forces, one of the officials said. The plan never materialized, as far as investigators could tell.

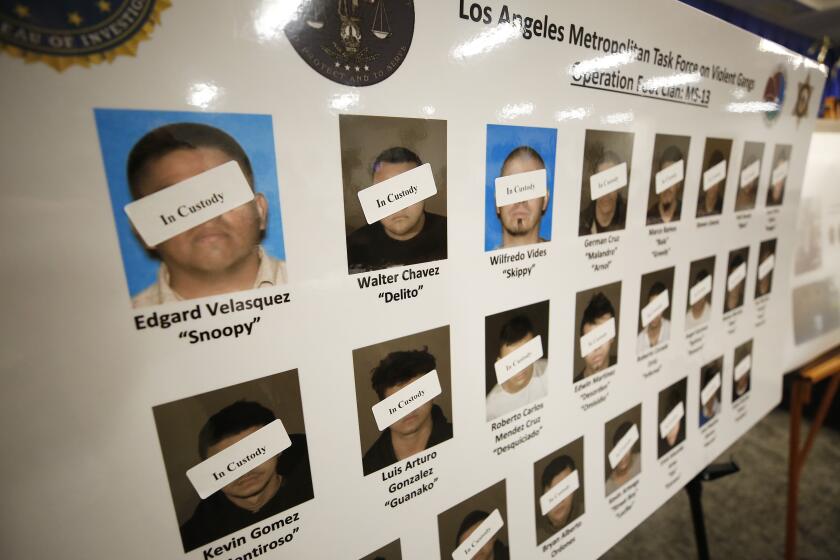

Ten reputed Park View members and associates were swept up in 2015 and charged with murder, attempted murder and extortion. Their cases, filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court, remain open. Flores wasn’t charged in the investigation.

It is unclear when Flores was apprehended in Mexico, but he did not enter U.S. custody until May. He made an initial appearance in federal court in San Diego before his case was transferred to Columbus. He faces an indictment returned there in 2017, while he was living in Tijuana, charging him with extortion and money laundering.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.