As a boy in Compton, Richard Perry raised pigeons that were bred to tumble in the air. Now, as he lay in a hospital bed fighting to breathe, drifting in and out of consciousness, he saw his birds somersaulting across the sky.

For the four weeks that COVID-19 tried to kill him, Richard had nothing to do but wander through his mind. Thoughts of death and leaving his wife and daughter to struggle sent him into a panic. So he traveled back.

He was playing football in the street with his brothers Ray and Ronald, waiting for their mom to call them to dinner. He was letting his birds out of his backyard loft, a burst of squeaky wings. He was building bikes from scrap parts with his best friend, Dwayne, trading rims for handlebars, a rusty chain for grips, riding to the old Pike in Long Beach.

From his hospital bed in the weeks after he arrived Jan. 5, he thought about working on his first car with his dad. The hours together wrenching on a broken-down 1965 Chevy Impala — the spare words and scraped knuckles — set him on the path to become the man he would be.

At 58, Richard had a solid union job transporting and assembling satellite parts at Boeing Co. He was the one to whom his siblings came for help, the one his dad picked to take care of their mother if he died first. He had a wife of 34 years, Audrey; a grown daughter, Aushlie; and a house in Compton that he spent his weekends tirelessly remodeling and expanding into a family palace, with a rumpus room, sprawling patio and three barbecue pits to cook chicken and ribs for his brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews.

Richard claimed his berth in the middle class the way most Black people do — by sheer drive and against the odds, with little or no generational wealth to lean on in a crisis.

His father, Lapolum Perry, had left Jim Crow-era Arkansas for something bigger than a clearing in the woods with a rough-hewed cabin and an outhouse. When he landed in Los Angeles with a wife and young children in 1958, he worked as a truck driver for Shell Oil and in a year had saved enough to buy a little house in a tract of west Compton that was built for Black families aspiring to the middle class. Richard’s parents took a big step up in that purchase, and he took a big step up from that.

“I’m afraid I’m going to lose everything I worked all my life for. The moment I got sick, everything just started falling apart.”

— Richard Perry

Now COVID-19 was showing how rickety this ladder was. By mid-January, Richard was watching the virus rip through nearly every aspect of his life, as it was doing to home after home, block after block in Latino and Black neighborhoods from Wilmington to Watts, Pomona to San Fernando.

If he died, his family might fall into poverty. His mother would be crushed. Then he worried that his own negative thinking was going to be the final blow. He needed to keep his mind aloft. And so off he went, sorting through his memories for meaning.

“I’m afraid I’m going to lose everything I worked all my life for,” he told a reporter visiting him in the hospital one day. “The moment I got sick, everything just started falling apart.”

He hadn’t returned to work since the Christmas holiday, and the paychecks had stopped coming in — while the bills did not.

Audrey lost her job cleaning airplanes at Los Angeles International Airport. He told her to turn in his leased Jaguar so they could pay the mortgage. Their Lincoln Continental would be next. They had been in the process of refinancing their house when he got sick. When the lender learned he had stopped working, it canceled their application.

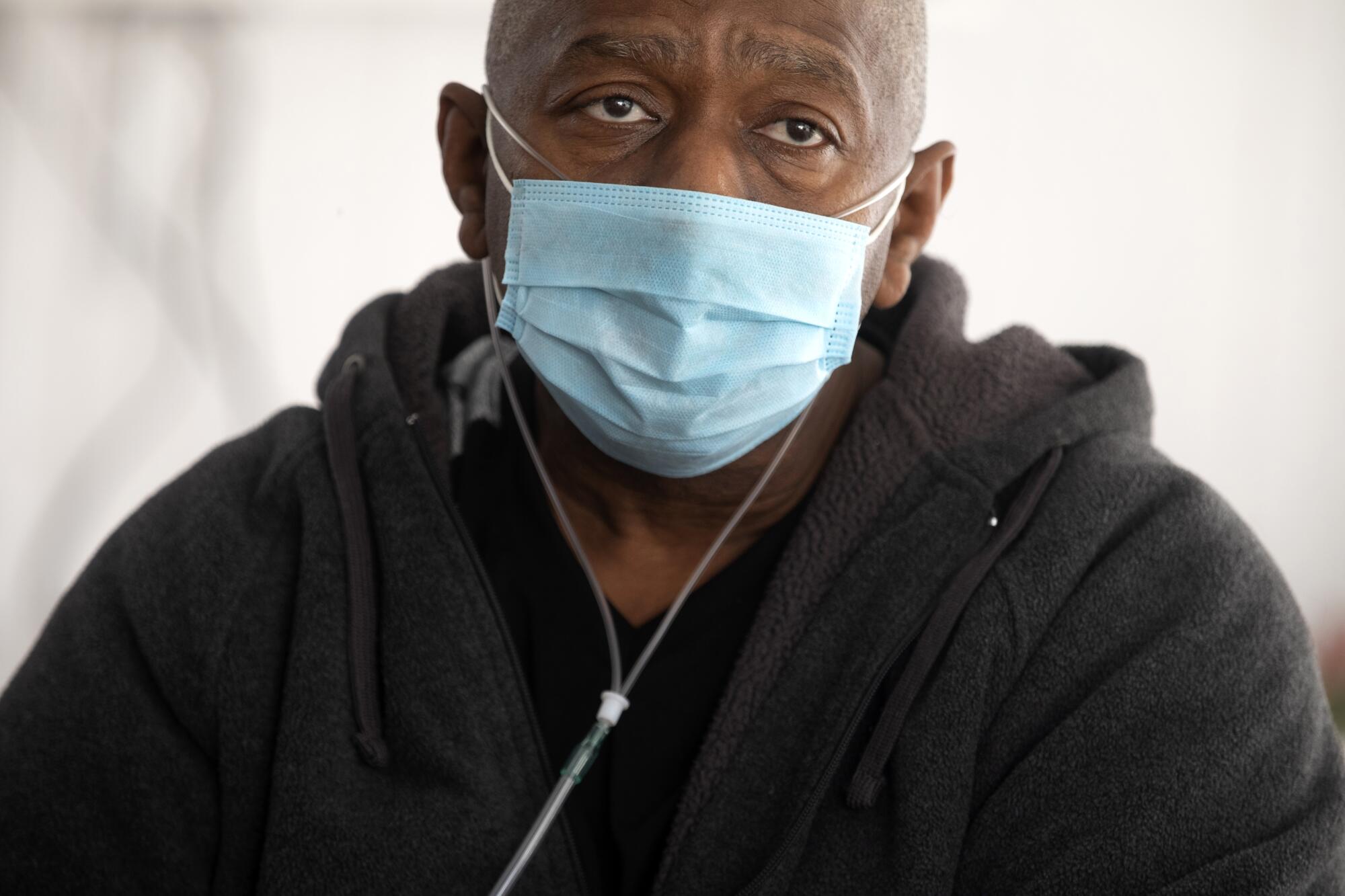

Richard didn’t have the energy to make the phone calls and navigate the web to get his disability paperwork in order. He had no laptop. His brain was foggy. He couldn’t even sit up in bed without his blood oxygen dropping dangerously low. Normally clean-shaven and well-groomed, he had a thick gray beard and a painful ingrown toenail.

He was simply trying not to die.

It seemed that every call from home brought a new burden to bear.

One day it was the plumbing.

“I’m trying to see who I can call,” Audrey told him. “It’s still backed up right now, the toilet, the kitchen, everywhere.”

Richard closed his eyes and exhaled. His face was sunken. He lay flat on the bed, on his side to get more airflow.

He lifted his oxygen mask off to be heard.

“So we need to get a plumber out,” he said.

The words came out weak and shallow. His blood oxygen numbers dropped on the monitor by his bed. He replaced the mask and inhaled deeply.

“I don’t see how we can afford it to do that,” she said. “You’re in the hospital.”

He again pulled the mask below his chin.

“Well, you got to get it done.”

Normally, Richard would snake out the clog himself. It pained him to hire any type of handyman. At home, he did everything — appliance repairs, tile work, mowing the lawn.

He thought about asking his oldest brother, Lapolum Jr., to help, but he had also contracted COVID-19 and was just out of the hospital on supplemental oxygen.

“So is my unemployment complete?” he asked.

“No,” Audrey said. “The check’s smaller than the last time. I’m trying to find out what’s going on. Because it’s real small. I’m going to call her first, then I’ll call the plumber.”

“I wish I could make all these calls,” he said. “I know I’m relying on you to do everything.”

After these conversations were over, he often fell into despair. Two nights early in his hospital stay, he had felt he came so close to dying that it haunted him every day after.

::

Richard started feeling sick on New Year’s Day. By Jan. 5, he was lying on a gurney in the back of an ambulance, shaking uncontrollably and gasping for air.

His brother Ray peered in from the back of the ambulance, head hung down, looking scared and forlorn. Ray was Richard’s older brother by a year but was the sweet, jovial kid who never quite grew up. He never married or moved out of his parents’ home, and he was as gentle a soul as Richard knew. The expression on his face made Richard tear up.

“I gotta go,” Richard said. “Bye.”

Richard arrived at the emergency room of Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital with blood oxygen saturation of 56% — a level low enough that it would normally kill a person within hours, if not minutes.

Doctors put him on high-flow nasal oxygen. If his saturation did not rise to a safe level, they would have to induce a coma, intubate him and put him on a ventilator. The intensive care unit was full, so they couldn’t fit him in. They put him in Room 533 on the fifth floor and had him lie prone.

He was stunned when doctors talked to him about next of kin and his wishes for being put on a ventilator if his organs began to fail.

Nurses and doctors checked on him, gave him his medications, brought him his food. But mostly he lay belly down, face to the bed railing, alone.

His mind meandered as the hours passed, his sense of time fell away. He wondered why his dad bought that broken Impala when he was 17. Richard was an usher at the Vermont Drive-In Theatre in Gardena and gave his dad enough cash to buy a working car, as he had done with Richard’s two older brothers.

His father was a bit of an enigma to his city-reared children. Part Cherokee, he grew up on a tenant farm in the bottomlands south of Pine Bluff along the Arkansas River. As a boy, his parents had sent him out with .22-caliber rifle or cane pole to catch a squirrel or possum or catfish for dinner. Out of sheer poverty, he learned how to fix anything with his own hands. And all his life, he refused to go to a restaurant, for the waste of money it represented.

As a child, Richard couldn’t grasp how hard his dad was fighting to keep his family afloat in Compton. At one point, Lapolum was driving his own big rig all over the West, hauling recycled paper. He lamented being away from his family five days a week, but he had to pay the bills. When trucking wasn’t earning enough, he took a job as a foreman at a metal polishing business and spent his nights and weekends fixing up old cars and motorcycles for resale.

The Impala arrived on a tow truck one day in 1980.

“I gave you $800 for a car that don’t run,” Richard told his dad.

“Yeah, you got to put another transmission in, you got to rebuild the motor, put shocks on it.”

“I got to rebuild the whole car!”

“That’ll make you stronger.”

That fall, Richard and his dad took the cylinder heads off, lifted the engine block, removed the pistons, put on new rings, replaced the rods and bearings, adjusted the valves. They rebuilt the carburetor and installed new brakes and shocks. After four months, they were nearly finished. Richard sanded down the body and primed it. He couldn’t wait to show it off to his friends, and to girls at Compton High School. His first drive was to his drive-in job, the V-8 engine rumbling nice and throaty, Kool & the Gang pumping, as he cruised down Vermont like a king.

Just before he pulled into work, an old man ran a stop sign at full speed and T-boned the Impala’s fender on the driver’s side.

The car was totaled.

Richard stood on the corner, not sure whether to weep or rage.

Now, so many years later, in his hospital bed, he confronted this same feeling of grand injustice on a cosmic level.

His coughing was getting worse, and he was starting to panic for air again.

Richard’s oxygen levels dropped to 69% in the early morning of Jan. 7. He coughed so hard he vomited. Nurses rushed in and added a re-breather mask that increased the oxygen he inhaled through his mouth. They patted him on his back. “You’re going to get through this.”

A doctor from intensive care considered putting him on a ventilator but held off.

Richard prayed day and night.

Look, God, I been doing everything I can all my life to do the right thing. I followed the rules. I didn’t do drugs. I didn’t drink. I always respected everybody. And you want to take me? Give me another chance. I want another chance in life.

The next day, Audrey told him that his brothers Ray and Ronald were both taken to the hospital with COVID-19. She and their daughter Aushlie had also caught it, but their symptoms were not bad.

As he lay there after the call, he remembered playing slot cars with Aushlie when she was a little girl. They loved that. He regretted that he never introduced her to roller pigeons. She texted him a photo of them together to cheer him up. His eyes welled up looking at her smile.

On Jan. 14, Audrey called with terrible news. His older brother Ray had died.

Richard fell into a sinkhole of grief. He kept seeing Ray’s saddened face peering into the back of the ambulance. He was angry that Audrey told him. He couldn’t fight this disease and grieve at the same time.

“Don’t call and tell me anything else,” he told her. “The more you tell me, the more I stress out.”

As best he could, he tried to put Ray in a compartment to mourn later when he was healthy.

His lifelong friend Dwayne called to try to lift his spirits, remembering their bike treks to Long Beach and Redondo. So did a co-worker at Boeing, Raymundo Mena.

A shy man, Mena, 57, always appreciated how Richard went out of his way to make sure he was included, whether on business trips or just going out to lunch. When Mena was in the hospital for a heart problem, Richard was one of two people to call and sent a get-well card that he had everyone at work sign.

Now, Mena texted Richard photos of their travels together, delivering satellites to countries including Kazakhstan, Peru and French Guiana.

In Kazakhstan, the locals had treated Richard like a celebrity because he was the first Black man they had ever seen. They lined up to pose for pictures with him and ask for autographs. Texting, Mena reminded him of the haircut he got there, from a woman who had never seen a Black man’s hair, much less cut it. She mowed a bare landing strip up the backside of his head before he could stop it. He and his crew laughed over that the rest of the trip.

These reveries forced him to focus on getting better.

He started doing exhaustive breathing exercises on an incentive spirometer to expand his lungs. He managed to put his socks on by himself and sit up on the edge of his bed. He made progress one day, only to fall back the next.

Doctors were still deeply concerned that he might not make it. He had been struggling on the high flow of nasal oxygen now for 20 days, and that put potentially deadly strain on his organs. They’d seen people in his state, improving, only to suddenly fall into kidney failure or cardiac arrest.

On Jan. 27, he learned that his brother Ronald had been put in a coma and hooked up to a ventilator. Ronald was the tightly wound, argumentative counterpoint to laid-back Ray. A common family description of him is “roostery,” and Richard had had his clashes with him. But Ronald had a tender spot for children and was always there for anyone in need. He and Richard had the same deep bond they did as children, playing football on West Tichenor Street with Ray, under the Japanese elm their dad had planted.

He tried not to sink into a sense that the worst was inevitable.

When a Times reporter and photographer visited the next day, he showed off a photo of him and Aushlie buying her car.

“Reminds me what I got, and hopefully I still have this stuff when I get back. I don’t know what I’m going to have. I fight so hard. I do whatever they tell me to do. Because I want to see my wife and my daughter again.

“She loves to hang out with her dad.”

On Feb. 3, he woke up without fatigue. His mind was clear, and he wanted to exercise. The next day, he did arm lifts, stood in the walker for 10 seconds and sat on the edge of the bed for 10 minutes.

Feb. 5, a month after his arrival, he successfully walked from his bed to the window and back.

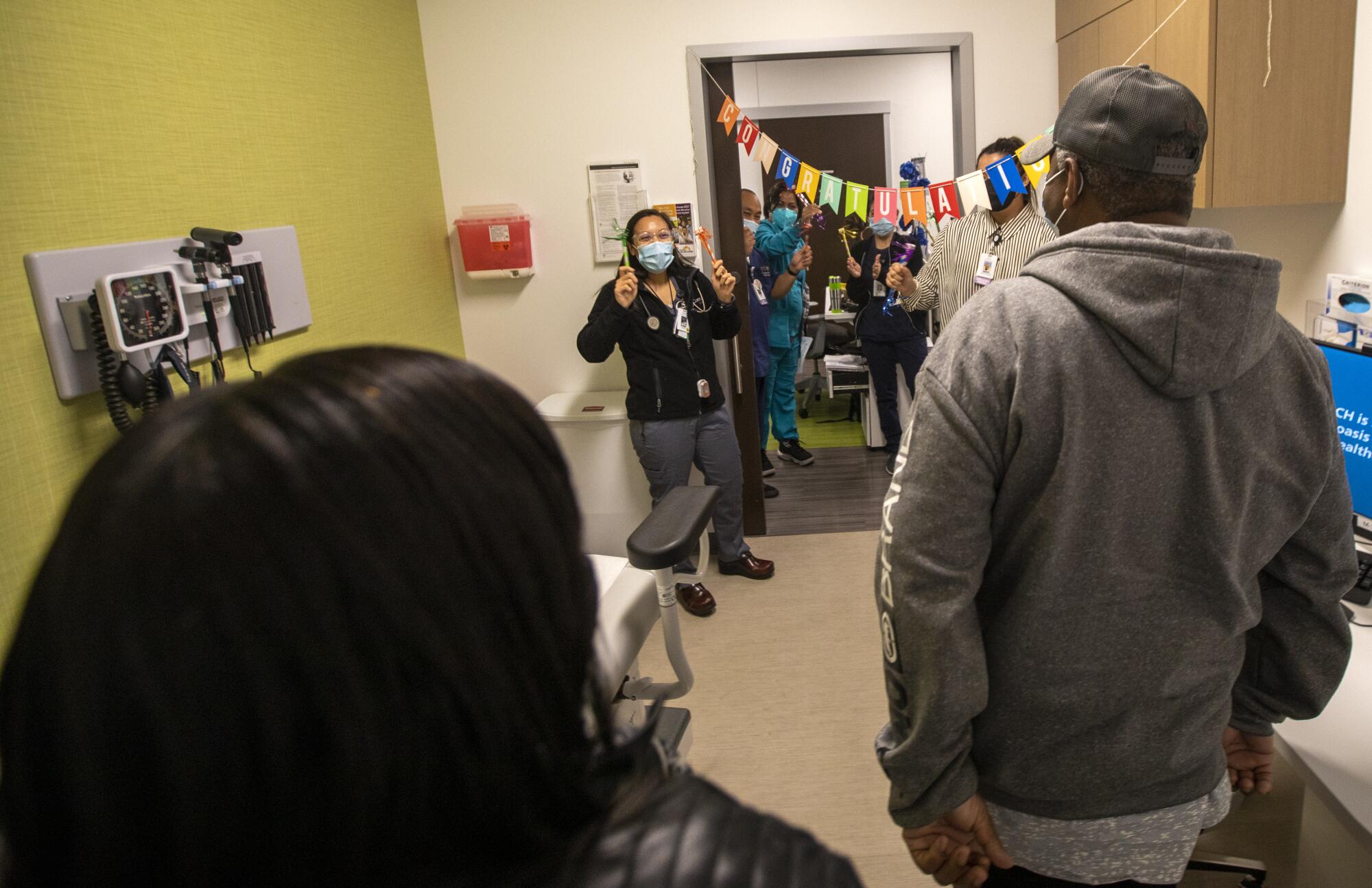

From that point on he walked farther and farther — until he was finally released Feb. 12.

As he was wheeled down the hallway with an oxygen tank, his nurses and doctors and therapists, who had seen so much death over the last two months, lined up to applaud him and wish him well.

At the entrance of the hospital, Audrey threw her hands up when he was wheeled out.

“Hi, honey, is that really you?” she asked.

“Yes, it’s me, I made it.”

She bent down to hug him. He rested his head on her shoulder.

::

Richard couldn’t go to Ray’s funeral because he couldn’t walk up and down the hill, even with the oxygen canister he towed behind him.

His friend Dwayne brought him breakfast while his wife and daughter attended the memorial. They laughed and cried and talked about old times. It felt like Ray might walk in the door any second. Richard still felt that about his dad, who died three years before.

He missed the old man. Richard had done everything he could to get him the best medical treatment, and then secured him a nice resting spot under trees at Rose Hills Memorial Park. His dad loved trees from his days in Arkansas.

Ronald died March 1, after more than a month on the ventilator.

Now Richard worried about his mom. Ruby Lee, 90, was devastated about losing two sons, both of whom were living with her in the old family home on Tichenor before they were taken to the hospital. With them gone, she started showing signs of dementia, calling Richard regularly in the middle of the night to say somebody was trying to get in, screaming that she didn’t want to die alone in a nursing home.

Richard couldn’t return to work unless he recovered fully. He still felt that he was on the precipice of financial collapse. The disability checks he’d received were a small fraction of his salary.

He had come so far from where his dad had started — hunting game for dinner as a youth. Now his footing still seemed so shaky.

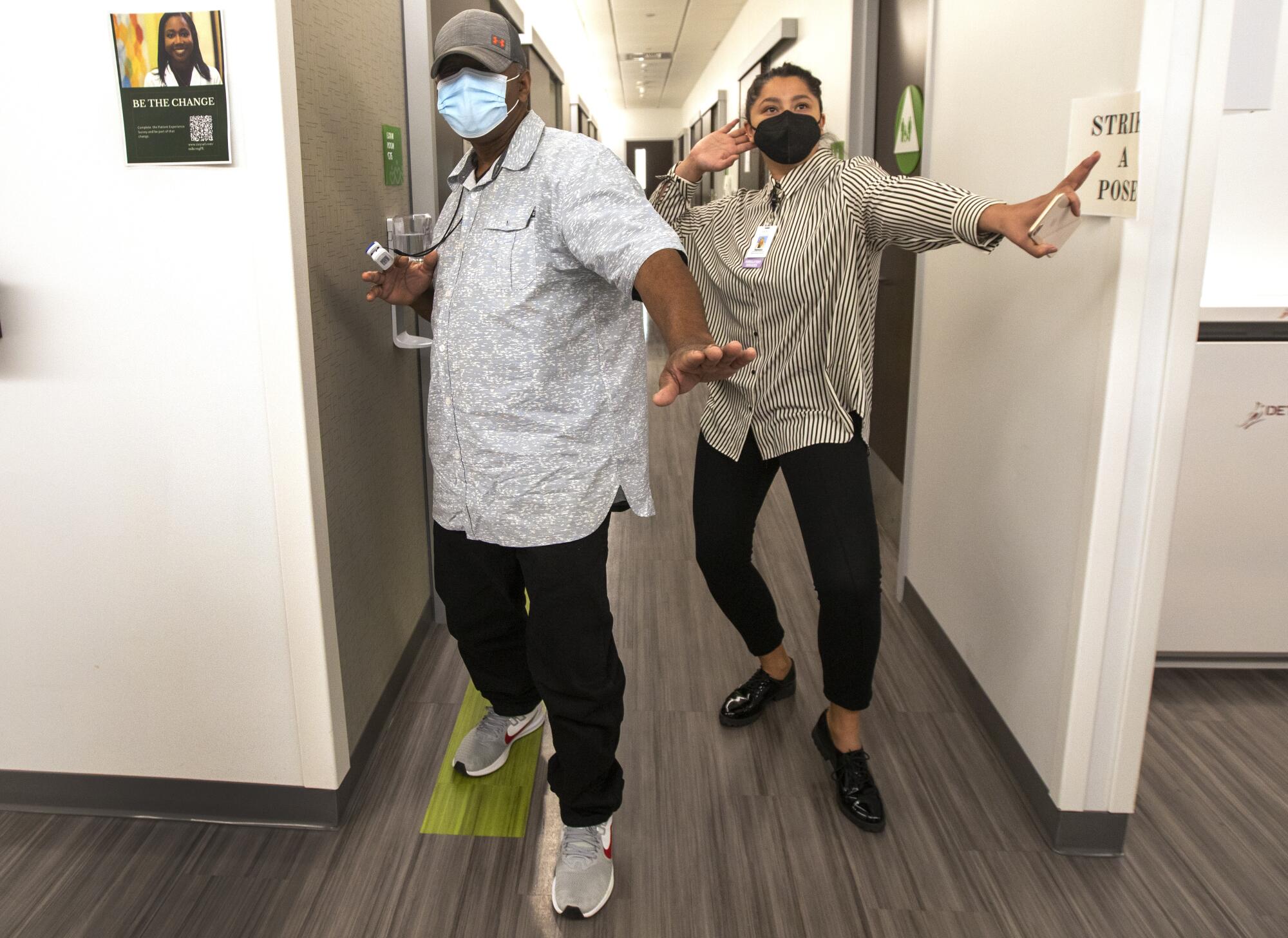

Once a week he visited Martin Luther King’s COVID-19 ICU post-discharge unit for doctors to check his progress. Dr. Erin Dizon, an infectious-disease specialist, marveled at his recovery and, perhaps most important, helped him get all the forms filled out to receive his full disability payments.

By March, Richard no longer needed the supplemental oxygen, and the disability checks were coming in. His mother was in the hospital after several strokes. He would take care of her like his dad told him to do.

He figured he could make it now. That existential dread had receded. He thought of the Impala from time to time. The driver who totaled it was an old man with trembling hands who said he was racing home to get to his medicine. He promised his insurance would pay — and it did.

Richard bought a cool, clean 1973 Monte Carlo — maroon, with cream leather seats. He wooed Audrey in that car and made a life he was determined to keep.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.