Collecting memorabilia from biker gangs, he earned friends — and death threats

Mother Ruthe.

It was a name Bo Bushnell had heard again and again as he sought out memorabilia from the outlaw motorcycle clubs that thrived in Southern California during the 1950s and ‘60s.

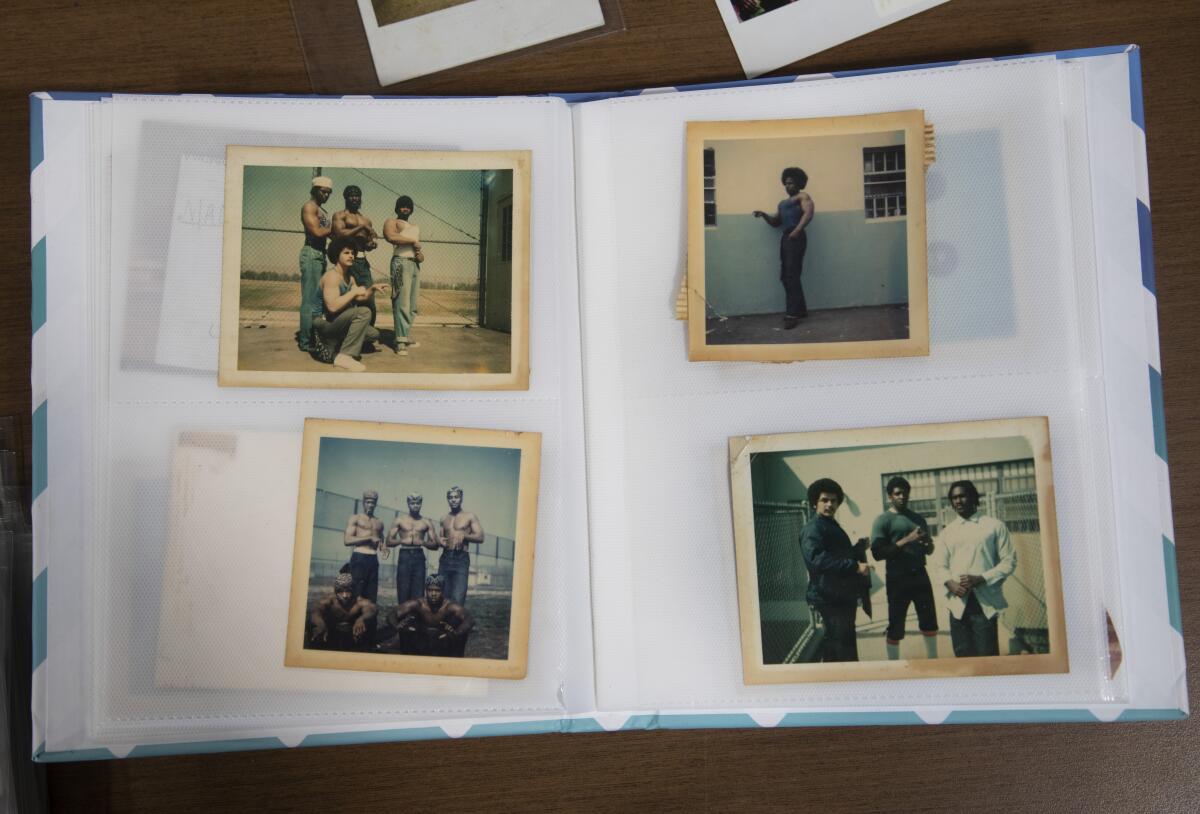

Since he’d started collecting, he’d bought photographs, clothing — even a couple of motorcycles. But the bikers he talked to often told him he should try to find out what had happened to Mother Ruthe’s scrapbooks.

She had lived in La Puente, located conveniently halfway between biker clubhouses in Venice and San Bernardino, and acted as sort of a den mother to riders who stopped at her house. She fed them, patched up their wounds, let them crash for the night. And she photographed them and collected news clippings about them.

The problem was, she had died, and no one Bushnell had talked to knew her full name.

::

In the beginning, back in 2013, Bushnell hadn’t even been interested in motorcycles. He wasn’t looking to collect photos of outlaw biker gangs. And he certainly wasn’t looking for trouble.

Bushnell was working for punk memorabilia collector Bryan Ray Turcotte, who had hired him to work on Turcotte’s “Art of Punk” documentary series for L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art and to help him build his collection.

When Bushnell was first offered a batch of pictures of 1960s Southern California motorcycle riders, he wasn’t interested.

But when he later learned that some street gang photos he knew had recently been purchased for $2,500 were resold a short time later for $45,000, he went back to the seller with the biker photos. With Turcotte’s help, in November 2013 he paid $7,500 to acquire the collection, which had belonged to two Venice members of the Straight Satans.

After acquiring that first cache, Bushnell was hooked. He began tracking down former members of the various clubs, befriending them, asking them to tell their stories and offering to buy their memorabilia from years past.

Turcotte was impressed with his determination. “He was obsessed in a hyperfocused way, like, one glimmer of light and he’s down the rabbit hole,” the punk collector said. “The dude just doesn’t care.”

But Turcotte also worried. The biker gangs Bushnell was dealing with didn’t shy away from violence, and Turcotte recalls telling his friend, “I don’t know how you do this without pissing people off.” Bushnell was unmoved.

It was the bikers and their stories that Bushnell loved, and he spent enormous energy tracking them down.

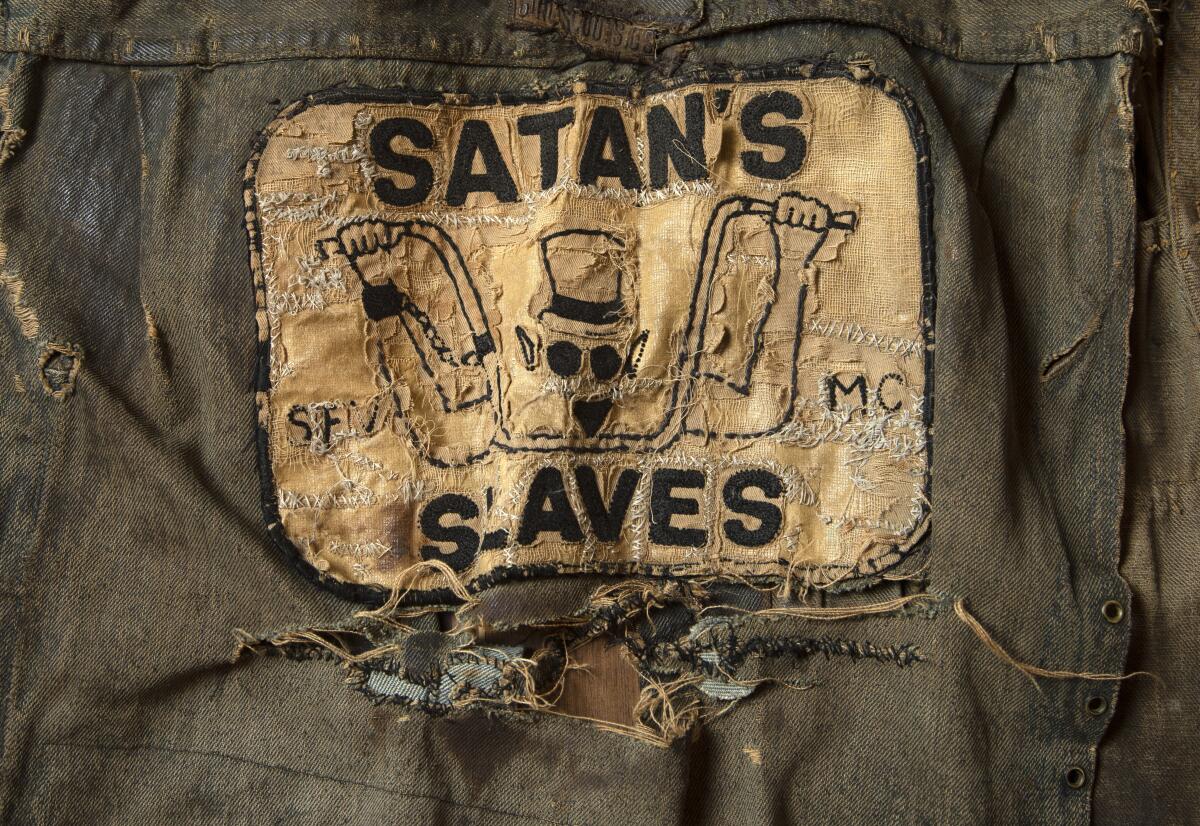

Early on, he met a man named Droopy, who was dying of cancer but agreed to talk to Bushnell about the old days, eventually bringing out pictures from his time as a Straight Satan. Later, he agreed to sell Bushnell his patches, which bear the club insignia and logos. Fledgling members must earn their patches, and they are never to be given away or sold under threat of serious reprisal from the club.

In early 2014, when word got out that he had the patches, Bushnell says, he got a call from a man who identified himself only as Doug and told him he was messing with the wrong people and was going to get hurt. Bushnell figured out Doug was a Hells Angel who went by Dougie Poo, so he called the biker back and convinced him to meet. Through Dougie Poo, he began to meet other riders as well, including Buzzard, Raunchy Pat, the Judge and Bill the Shark.

Though he found some of the stories they told him appalling, Bushnell related to the bikers as human beings, recognizing them as fellow outsiders.

The men told him about the early days of motorcycle gangs. Back then, he says, “it wasn’t about being a steroided-out monster looking for a fight.” They saw themselves as “a bunch of 20-somethings who wanted to ride, get loaded and live like 12-year-olds, forever.”

Over time, Bushnell began to record the stories they told him on audio and videotape.

Buzzard told him about the night he got Dougie Poo and a woman he was with high on booze and pills. When they passed out, he handcuffed them together in a compromising position, then called Dougie Poo’s girlfriend and asked her to come take him home.

This was revenge, Buzzard explained, for the night Dougie Poo had urinated on his leg at a bar.

The women who rode with the clubs had their own stories. There was Yum, so named because she danced at the Yum Yum Celebrity Club (“Always Open, Never Clothed”). She ran with Lil Bob, originally a Hells Angel and later a Coffin Cheater. There was Lil Bit, aka Margot, who rode her own chopper and was married to Coffin Cheater co-founder Lil Tom.

::

As Bushnell heard their personal histories, he grew determined to find Mother Ruthe’s scrapbooks.

In early 2015, a chance introduction from Dougie Poo led him to Harold, a former Hells Angel who’d been married to Ruthe decades earlier.

Harold knew Ruthe’s last name, and he knew she had died. But he had no information about whether she had living children, or where they might be.

Months of painstaking research using online databases led Bushnell to two women living in Florida who turned out to be two of Ruthe’s three daughters. They told Bushnell their mother’s things were in storage somewhere in Los Angeles, under the control of their other sister, from whom they were estranged. It took Bushnell months to locate her and persuade her to meet with him, he says.

She showed him some of what she had — scrapbooks containing hundreds of candid snapshots of bikers, along with clothing, membership cards and patches. But while she was willing to let him take some things to be photocopied, she said she couldn’t part with the memorabilia without the permission of her sisters — and Bushnell had to promise not tell them that he had found her in L.A.

It took months, but after almost a year on the hunt, Bushnell persuaded all three sisters to let him have the photos. The sister in California didn’t want any money. Bushnell sent the Florida sisters $1,500 each.

::

Today, Bushnell’s collection has grown to about 35,000 items. And in building his archive, he has rescued a significant chapter of Southern California history from the trash heap and become a respected authority on local bike clubs, the outlaw biker movement and the birth of the Hells Angels.

The soft-spoken, heavily tattooed (partly by L.A. ink artist Dr. Woo) Bushnell, born Robert Addison Bushnell III, was destined to be a collector. His beloved granddad was a successful Boise businessman obsessed with acquiring original Remington statues, Central European copper pots and other collectibles. His father went for Steuben glass and Tiffany lamps.

As a child, Bushnell developed his own obsessions — hot rods, skaters and punk rock. He subscribed to Low Rider magazine when he was 9 and began attending rock concerts before he was a teenager. He struggled with ADD, was prescribed Ritalin in the third grade and found school difficult, said his mother, Laura Bushnell, who described him as “mind-blowingly intelligent” but “not exactly normal.”

After a year of college and a series of jobs developing internet sites and reality TV shows, he met Turcotte and found his calling.

Early on in his collecting, Bushnell published some of the photographs he’d collected in a series of zines to raise money to acquire more material. In late 2015, after acquiring Mother Ruthe’s collection, he made plans to bring out his first book, “Halfway to Berdoo,” which would feature Mother Ruthe’s snapshots along with stories he had collected from the bikers she photographed.

Not long after, says Bushnell, the pressure mounted. Word reached the Hells Angels organization that Bushnell was intending to publish his book. Two members who had told Bushnell their stories were called into a meeting, Bushnell said, and told that if the book was published and contained details they’d provided, the members and their families would be killed. Bushnell received the same message.

According to former Hells Angels attorney Fritz Clapp, who for 30 years represented the club in trademark cases and became an early Bushnell supporter, the threats were real and credible.

“He had death threats — actual death threats,” Clapp said. “He was afraid for his life.”

The two club members begged him not to publish. Friends advised him to back down. Former club member and Bushnell fan Bill the Shark, who had also been a Galloping Goose, said he was worried. “I grew up in that world,” he said. “I saw some crazy s— go down.”

Bushnell took the threats seriously. His mother says that when she posted a happy birthday message to her son, in her own name, on his Outlaw Archive Instagram page, he called and said, “Mom! Never do that! They’ll find you!”

But despite his fears, he had no intention of backing down. Having spent all his savings and maxed out his credit cards acquiring material, he was living out of his car, showering at his gym and staying occasionally in Airbnb rentals. He needed the money that would come from the book.

“I was sort of hiding out, but I felt like, if they wanted to kill me, they could definitely find me,” Bushnell says now. “I didn’t think they would.”

As an insurance policy, Bushnell posted proof of the threats on his Instagram page. Former club attorney Clapp contacted an Angels representative and tried to talk the club down, Clapp said. He put Bushnell in touch with the club’s criminal attorney.

After Bushnell published, and the Angels were sent a copy, the furor died down.

A Hells Angels Motorcycle Corp. attorney in San Francisco agreed to contact club members to see if they would comment for this story. She said none of them responded to her request. Hells Angels leader Sonny Barger, reached by text, declined to answer questions, saying, “There is really nothing to comment on.”

::

Bushnell’s biker archive, which he named the Research Institute of Contemporary Outlaws (or RICO), is now being professionalized with funding from a local entrepreneur and the help of two former UCLA archivists. It is stored inside an unmarked red brick warehouse near downtown Los Angeles, behind a 2-ton bank-vault door in a hardened metal room, encased in four feet of steel, rebar and concrete.

Also in the showroom are several Harley-Davidson choppers in varying stages of decay, which Bushnell acquired from club members, and a beautifully customized ’64 Chevy Impala — because he’s still into lowrider cars.

For a recent visitor, Bushnell took out prized documents, pieces of clothing and other collectibles, including belt buckles, knives, roach clips, wallets and a Star of David sissy bar (the metal backrest for a passenger) handmade by a Jewish club member named Angel Marc. Bushnell especially values the meticulously crafted Zippo-style custom lighters that a craftsman named Andy made for the Ventura Hells Angels chapter.

Bushnell is proud of his collection, in part, because of the relationships he has built in the process of acquiring it. He recalls, for example, the time he got a phone number for former Hells Angel Allen “Gut” Turk, a graphic artist who designed album covers, T-shirts and posters for the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and others. When Gut said, “I’m in Reno. Come up some time and we’ll talk,” Bushnell drove through a blizzard to get there the next day.

Bushnell visited Gut repeatedly over the next two years, orchestrating a reunion between the biker and musician David Crosby, who had been Gut’s friend in the 1960s.

When Gut was close to death, Bushnell, without asking for permission, contacted Gut’s brother and one of his long-lost friends, neither of whom Gut had seen in decades. They were able to visit him before he died in 2018, and later the brother offered Bushnell Gut’s personal items, which included his Hells Angels “colors.”

With 135,000 followers of his Outlaw Archive Instagram account, Bushnell now has people with biker memorabilia reaching out to him, and he still finds treasures in unexpected places. While negotiating the price of an Eames chair from a seller on Ebay, the seller mentioned that he also had some files he said came from a former gang cop. In it were the names of all active Hells Angels members, with photographs, case numbers, dates of birth and more. From that, Bushnell was able to locate relatives of members who had died or disappeared, and purchase still more material.

Building the collection has gotten easier since Bushnell met the successful personal injury attorney Paul Zuckerman, well known in the car world as sidekick to Spike Feresten, the former “Seinfeld” writer who now hosts the podcast “Spike’s Car Radio.” Zuckerman was following Bushnell’s Outlaw Archive feed and reached out. They quickly became friends.

“He invited me to this little house where he was staying, and I saw a genius,” said Zuckerman, who later bought and equipped the warehouse that now contains the archives and hired the archivists to tend it. “He had done what journalists and historians should have been able to do, but never had done, which was to enter that world and really learn about it.”

Zuckerman was shocked to hear that Bushnell was so broke he couldn’t even publish new editions of his books to raise money, and he offered to bankroll the collector and his archive. The two reached an agreement: Zuckerman would spend whatever was needed to house, protect, preserve and expand the archive, and would become half-owner of the collection, past, present and future.

It’s a gentlemen’s agreement, with nothing on paper, and the details are a little fuzzy. When asked about the arrangement, Zuckerman sounded surprised to learn his co-ownership included things collected before he arrived on the scene. “He said that?” Zuckerman asked. “I’m glad he feels that way. We never discussed it.”

The exceptions are the items Bushnell acquired with Turcotte. Of those, Bushnell said, “Paul gets half of my half.”

What’s all it worth? Bushnell and his archivists can’t say, since there are few similar collections, and too few records of sales, for experts to make easy estimates. At one point, Bushnell said, a museum offered $750,000. Later, an appraiser guessed it might be worth $3.5 million. Bushnell and Zuckerman once said they wouldn’t part with it for $10 million. Now, Bushnell has doubled that: Not for $20 million.

The real value of the collection is its capacity to correct the monstrous image of outlaw bikers and give them their true place in history, said Paul d’Orleans, motorcycle historian and curator of the influential bike culture website the Vintagent.

“These few hundred club members had an enormous impact on our culture at large by their mere existence, and they also created a unique and peculiarly American folk-art movement with their custom motorcycles,” D’Orleans said. Like it or not, he added, “That movement evolved into a billion-dollar worldwide custom motorcycle industry.”

George Christie, former head of the Ventura Hells Angels chapter and for decades the de facto second in command to club leader Barger, agreed. “The historical record he’s keeping is important,” Christie said. “If I was still representing the organization, I would try to nurture a relationship with him, so this stuff can be categorized and put on display.”

Christie, now 74, and Bill the Shark, 79, a successful entrepreneur no longer active as a club member, also spoke to the urgency of Bushnell’s work. The original club members are old, and dying, and their heirs may not appreciate the value of their stories.

“We are the last of the Mohicans,” Bill said. “One-way Pete is gone. Judge is gone. Dougie Poo is gone. I’m still friends with Buzzard. Everyone else is dead.”

After the books and the Instagram handle brought Bushnell attention, Hollywood came calling. Bushnell has fielded interest from multiple interested parties.

But red flags come up immediately, said producer Alex Ott, who has worked with Bushnell on turning the collection into a film or TV series. When people hear the words “motorcycle club” or “Hells Angels,” despite the success of the long-running biker soap opera “Sons of Anarchy,” they think rape, murder and mayhem. “But there’s so much more to their stories,” Ott said.

Bushnell may face similar suspicions with his other collection. Having established what is surely the world’s largest collection of 1960s and ‘70s California outlaw biker memorabilia, he is now amassing a growing collection of photographs and personal effects of the earliest years of L.A. street gangs such as the Crips and the Bloods, which he is slowly sharing on his Instagram feed called the Streets.

It’s not that he’s obsessed with gangs any more than he was with motorcycle clubs.

“The gangs and the clubs, they’re just the backdrop,” he said. “It’s the people, and the personal stories, that fascinate me. I have always been interested in outsiders and outlaws, and these are the ultimate outlaws.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.