REDDING — It was a slow night in the trendy Market Street Blade and Barrel restaurant when line cook Nathan Pinkney, a budding comic and Black Lives Matter activist, spotted Carlos Zapata at the bar. He knew it meant trouble.

For weeks, he had been making political parody videos of Zapata, a high-profile militia member and a leader in a movement to recall a trio of Republican Shasta County supervisors who supported Gov. Gavin Newsom’s pandemic health orders.

Soon after the two saw each other, Zapata threw a drink at Pinkney, according to police. It escalated from there. That night, the BLM activist ended up with a black eye after two associates of Zapata allegedly assaulted him at the rear entrance of the restaurant while Zapata was present, according to police and interviews with people involved.

While the events of May 4 are disputed, the altercation involving Pinkney and Zapata has intensified tensions in this Northern California town. Known as the “second sunniest city in the U.S.,” Redding now feels to some like a tinderbox, with Shasta County residents divided over the health risks posed by the pandemic, government’s power and the degree that armed citizenry should take matters into their own hands.

Speakers at supervisors’ meetings have repeatedly threatened violence, militia members have attended racial justice rallies carrying concealed weapons and opponents of the far right say they are increasingly afraid to speak out, fearing retribution.

Zapata has been at the center of this fray, becoming a literal “poster boy” for a media campaign that hopes to redirect the energies of Trump supporters into local politics, and spread civic revolt nationwide.

Zapata, a 42-year-old Marine Corps combat veteran, made his viral debut in August. At a Shasta County supervisors meeting, he warned of potential violence if elected officials did not drop pandemic health restrictions. “It’s not going to be peaceful much longer. ... Good citizens are going to turn into real concerned and revolutionary citizens real soon,” he warned.

Pinkney and his supporters say they’ve long cautioned that militia members could turn their threats into action, and are watching to see how authorities will now respond.

On Monday, Redding police issued a statement about the bar fight that effectively held both parties responsible for what it described as a verbal argument that escalated into punches being thrown, adding that “none of the involved parties sustained any significant injuries.” No charges have yet been filed in the case, which has been referred to the district attorney.

The Times found several inaccuracies with the police version of events, which a police spokesman later acknowledged. Pinkney is also frustrated that sheriff’s deputies have not served a temporary restraining order he obtained against Zapata on May 6. Pinkney, who lost his kitchen job over the incident, said he’s become the victim of a “political hate crime,” a claim Zapata disputes.

Zapata, who owns the Palomino Room bar and restaurant in nearby Red Bluff, said he sees bar fights “eight times a night” that never make the news. He said he never laid a hand on Pinkney, adding that the local media has blown the altercation out of proportion and has taken Pinkney’s side.

The Shasta County Sheriff’s Office confirmed it had received the temporary restraining order against Zapata, who said he had not been served with it as of Tuesday. Pinkney’s lawyer, Lisa Jensen, said in addition to the sheriff, she tried to hire two private agencies to serve the order, which would require Zapata to relinquish his guns, but both declined, one citing a conflict of interest.

Zapata struck a brash note when asked about the order Tuesday. “There is not a person in this county who is going to serve that f— thing,” he said.

A Shasta County supervisors’ meeting was faced with verbal threats to government officials and talk of civil war. “You have made bullets expensive. But luckily for you, ropes are reusable,” one person threatened.

South of Redding, residents formed the Cottonwood militia more than a decade ago when five local businesses in the town were robbed on five subsequent nights, according to one of the group’s founders and leaders, Woody Clendenen. It has since grown from 11 members to a sizeable political force, including Zapata, with an increasingly savvy media reach across Northern California and beyond.

Its members are well-known in the community, offering a scholarship each year, hosting a boys’ camp, and sometimes being called in lieu of the police, said Clendenen.

“It grew into almost kind of a political action committee,” said Clendenen, a Cottonwood barber and bit actor in Hollywood B-movies. Candidates for office would call and court militia members for support, he said. Before the pandemic, he said, “our fundraiser dinners, the sheriff and the supervisors come.”

Over the last year, the militia has become more visible in its political action. This summer some of its members, including Clendenen, showed up at peaceful George Floyd protests, carrying concealed firearms, he said.

For some at the protests, including BLM activist Keito Obadiah, the presence of militia members was unnerving.

“People were scared,” Obadiah said. “Several came across the street, getting in our face.”

In response, Clendenen said his group was there, along with “stinking cowboys” and “bikers,” to help protect local businesses, and carrying concealed weapons was nothing out of the norm. “I’m carrying if I am out of the shower, so it doesn’t matter if I’m at that or shopping,” said the barber, who was armed with a Glock 26 while cutting hair at his shop during an interview with The Times.

During the pandemic, Shasta County Sheriff Eric Magrini made clear he would not enforce restrictions on businesses. Even so, the mandates became a rallying cry in Shasta and other counties statewide as “patriot” groups claimed their liberties were being trampled. Driven by that outrage, the Cottonwood militia has also backed efforts by an unaffiliated group to recall three conservative supervisors and replace them with like-minded “constitutionalists,” using videos to target elected leaders and “snitches” suspected of reporting businesses defying coronavirus restrictions.

In a video last year, Clendenen and Zapata issued a warning to those who informed on businesses defying health orders.

“Don’t think we are going to forget who you are because we are not going to. We know who you are,” Clendenen says in it, while he is seen sitting next to Zapata.

Zapata continues, saying his group is also collecting “intelligence.”

“We also have people on the streets. We know where you live. We know who your family is. We know your dog’s name,” Zapata says. “So if you think for one second that we are going to let you spy on us without us doing our due diligence and spying on you, you are absolutely wrong.”

As he has before, Zapata rejected claims that the statement was intended to threaten anyone, saying that “peace and safety” was a priority for his coalition.

“We’ve been accused of being insurrectionists and domestic terrorists, and calling for violence. No. All we’ve ever done is talk about the reality of, violence can happen if we fail,” Zapata said.

Critics say they are trying to have it both ways, claiming they are nonviolent even as they blast out incendiary messages around the recall and the pandemic.

“Their agenda is, ‘If you don’t agree with us then we have to get rid of you,’” said Leonard Moty, a former Redding police chief and county supervisor being targeted for replacement. “I am concerned for individuals in our community.”

Emboldened by their earlier video efforts, Zapata and Clendenen have recently transitioned to more slickly packaged content, including a 10-part documentary series, “Red, White and Blueprint,” aimed at an audience far outside Shasta County.

Marketed as the real-life journey of patriots determined to take back local control of their county, the series opens with dramatic music and drone shots of the mountains on an overcast day, someone in a field waving an American flag, and men in cowboy hats riding horses. The camera then tightens its focus on a woman firing a gun, followed by the sign outside the County of Shasta Administration Center, where the supervisors meet.

Each of the primary cast members — including Zapata; Clendenen; Terry Rapoza, a leader in the State of Jefferson secession movement; and recall organizer Elissa McEuen — now has an IMDB page, and the first episode drew more than 40,000 YouTube viewers. The series poster features a photo of Zapata in a cowboy hat. Coproducer Jeremy Edwardson, a Christian music producer, said the purpose of the documentary is “to expose a broken system.”

There also is money to be made. The sale of merchandise — including branded hats, T-shirts and camouflage drink koozies — is helping the project raise cash, as are local fundraisers, including a spring event that drew hundreds of people paying $100 per ticket.

“People may say, ‘These guys are capitalizing off it,’” Zapata said. “Yeah, we’re capitalizing. We’re capitalists. This thing has to fund itself. These documentaries are not cheap to produce.”

Moty said he is concerned that “Red, White and Blueprint” is raising large sums of “dark” money for its endeavors, and that the organization is acting as a political campaign that should be reporting its contributions and expenditures. He and the two other supervisors targeted by the recall filed complaints with the California Fair Political Practices Commission. Tuesday, the FPPC announced it would investigate those claims.

Congressman Doug LaMalfa (R-Richvale) attended a March event for the series premiere, gave a speech, and posed for a photograph with Clendenen and Zapata.

His spokesman, Bradley Jaye, said in an email to The Times that he “was in the area that day and was invited to come by as a guest. He was asked … to say a few words but was not part of a program or a listed/advertised speaker.”

Zapata — a jiu jitsu black belt who has offered martial arts training for law enforcement with a business partner who is a part-time police officer in the Siskiyou County town of Etna — said “Red, White and Blueprint” events have drawn officers “from every agency” in the local area.

“They know that if they start allowing all these social justice warriors to take root here, that turns into antifa. That turns into BLM,” he said. “Of course law enforcement is going to gravitate toward us.”

Spokesmen for both the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office and the Redding Police Department denied any affiliation with militia members, and stressed that the agencies treat all citizens fairly and equally.

“There is no strong ties to any group by any means,” said Redding Police Capt. Jon Poletski, who runs the detective division that investigated the altercation involving Zapata and Pinkney. “We want everyone in our community to feel safe.”

Supervisor Patrick Jones — a gun store manager who supports the recall and appeared on horseback in “Red, White and Blueprint” — said that anger festered during the pandemic, and that public comments from both sides can get volatile. He said someone who accosted him at board meetings recently made a death threat against him and his sister that he reported to authorities.

The effort to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom resonates in conservative Northern California, which has long been skeptical of leadership in Sacramento.

In Shasta County, there are wide views on whether Pinkney, a former Air Force Security officer who goes by the stage name Nathan Blaze, is a victim of extremist politics, or a provocateur. The comic has made more parody videos of Zapata since the fight, which was first reported by local independent journalist Doni Chamberlain. Multiple people contacted a Times reporter to allege Pinkney has engaged in harassment, profane language and threats online. Pinkney acknowledged postings that contained profanity, but denied issuing threats.

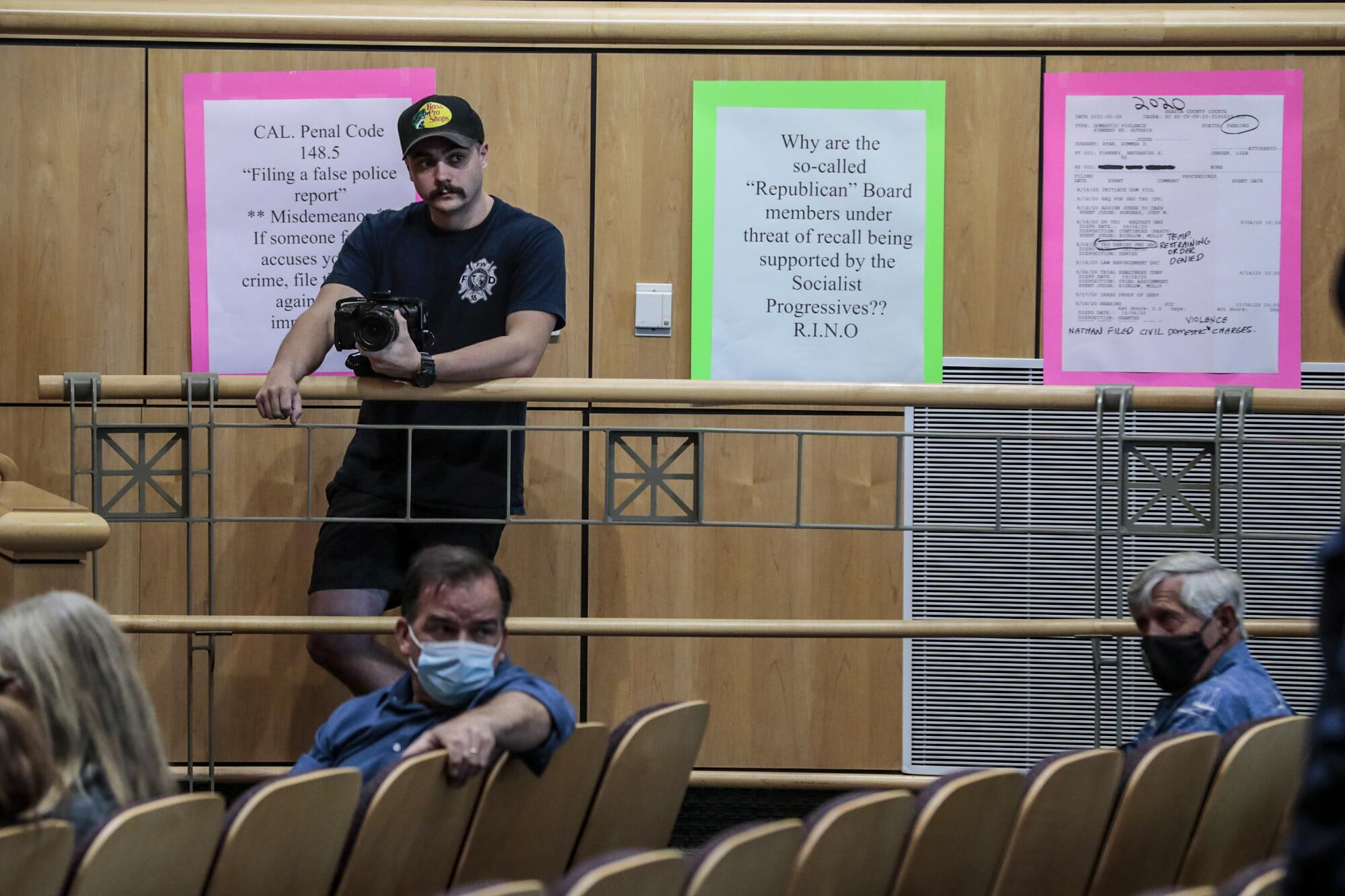

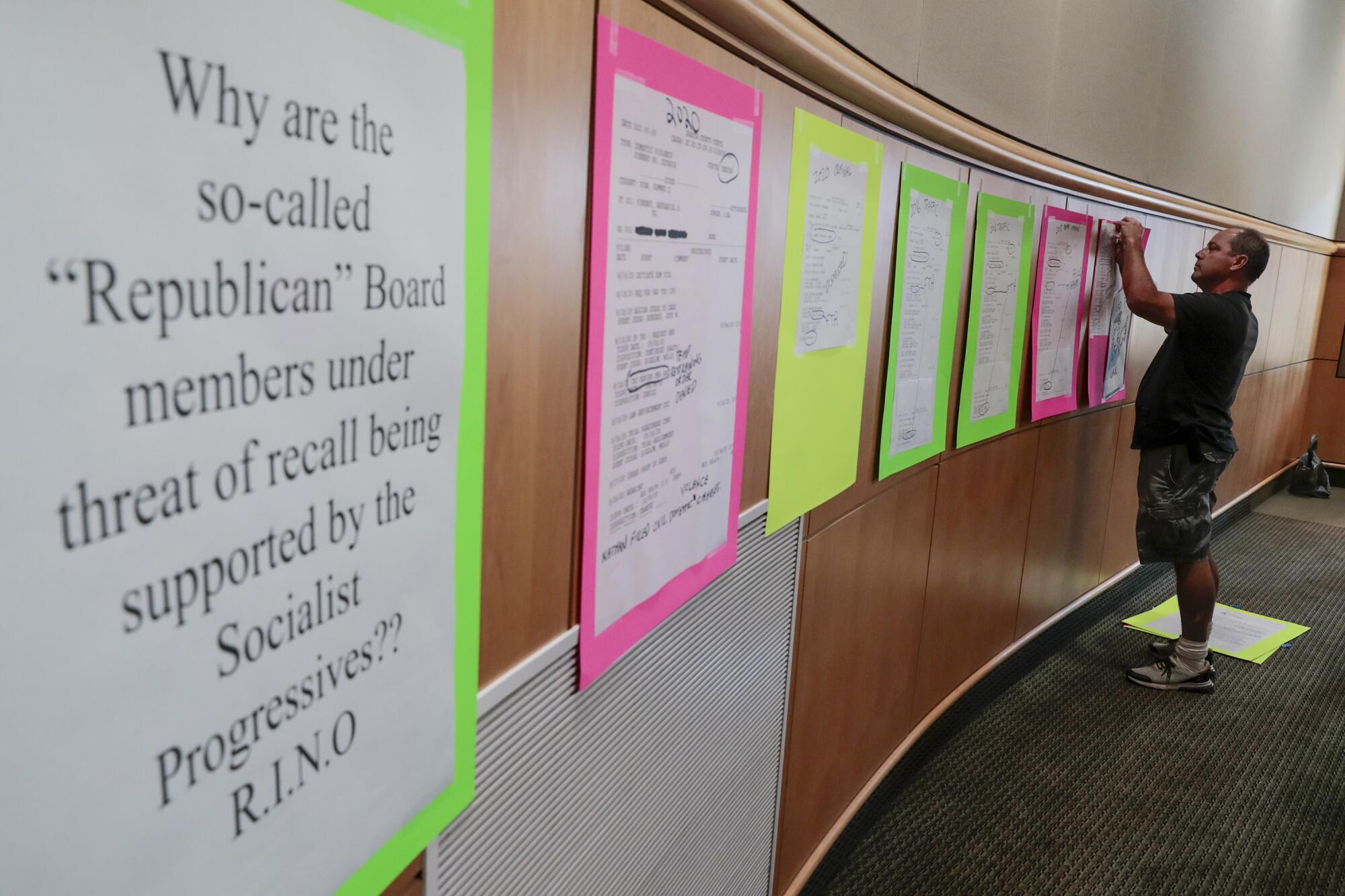

At the same time, he has been doxxed online with racist memes targeting his father, who is Black. At last week’s supervisors meeting, a recall supporter taped blown-up copies of Pinkney’s court record onto neon poster boards and hung them on the wall, including traffic tickets, notice of a restraining order against an ex-girlfriend who allegedly hit Pinkney with a frying pan, and a parody Facebook post in which Pickney says he is going to cook a steak using embers from an “antifa” fire he started.

“They are just bullies, you know,” said Pinkney of his opponents. “They are all so sensitive and volatile.”

In a Monday press release, Redding police made statements about the bar fight that Poletski, the police captain, later confirmed were inaccurate. These include details about where the altercation took place and claims coworkers had to “disarm” Pinkney after he retrieved a legally owned handgun following the assault.

Other details were contradicted by those involved.

Zapata said Pinkney did not follow him out of the restaurant and engage in a second verbal altercation as police claim. Instead, Zapata left in his car without seeing Pinkney outside, he said. Elizabeth Bailey, an associate of Zapata involved in the incident, confirmed she called Zapata to return after he had left.

Though police claim the incident took place in a parking lot, Poletski later said Bailey and her boyfriend Christopher Meagher confronted Pinkney at the back door to the restaurant where Pinkney works. It was there, Poletski clarified, that Bailey allegedly grabbed Pinkney’s shirt.

Meagher stepped inside the restaurant, Poletski said, where he punched Pinkney and hoisted a “large CO2” bottle, according to the press release, and held it toward Pinkney and his coworker, Kenneth Cornelius, in a “threatening manner.”

Poletski also clarified that Pinkney voluntarily gave the legally owned gun to a coworker when asked.

Cornelius, who is Black, said he heard the N-word repeatedly during the confrontation. Unsure if he was being targeted, he said he punched Meagher, which police confirmed. Poletski also confirmed that the police investigation documented racial slurs uttered during the encounter.

All these contradictions and turmoil have some local residents fearing more serious days ahead, and while many are urging county leaders to act, some are wary of putting their names in public.

The day Pinkney said he was assaulted, a woman in a wide-brimmed hat and face mask, her voice shaking, appeared at a county meeting. She said she had been harassed by people connected to the recall movement who believe she was one of those who spoke out against businesses that defied shutdowns.

Her property has been vandalized and people have parked on her street and watched her house, she told the supervisors.

Some readers see Doni Chamberlain and her website as a defender of civil society; others in Shasta County reject her as a liberal ‘laughingstock.’

“What I believe a true patriot is is somebody who loves his community members and doesn’t talk about taking up arms against them,” she said.

She then spoke directly to Supervisor Les Baugh, a pastor who is not a target of the recall effort, saying she was disappointed he was supporting people who had been threatening. An extraordinary exchange followed.

“I’m so disappointed, Les, because I really believed in you. I really did. And you support people that have made my life a living hell.”

“So, would you like to introduce yourself?” Baugh asked.

“They know who I am,” she responded.

“I don’t. I have no idea who you are,” Baugh said.

“Ask your buddies. Do you really think that I could openly say my name and walk out of here without a target on my back?”

“I have no idea,” Baugh said, as people in the audience pushed the woman to say her name.

“Don’t be goaded into revealing your name,” said Moty. “You don’t have to.”

Baugh did not return requests for comment, but the woman did. Her voice still wavers after what she said was a humiliating and frightening experience. She said she still feels compelled to speak out but dreads the consequences, especially if extremists take control of the county.

“They want to make this a place where only their kind is welcome.” she said. “It feels like a matter of time before they know who I am.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.