Behind the new show ‘Them’ is the ugly and true history of L.A.’s racist housing covenants

A new horror anthology TV series, “Them: Covenant,” is making news for its grisly depictions of violence against a 1950s Black family in their new home in the then-white city of Compton. Without the supernatural elements, the decades-long stories of Black people trying to take up residence in Los Angeles County’s white neighborhoods are more than scary enough.

L.A. didn’t start out that way. Of the 22 adults among the pobladores, the first settlers, who set up housekeeping and created Los Angeles in 1781, 10 had African ancestry. And the last governor of Mexican-ruled California, Pio Pico, was of mixed race.

And that was pretty much the end of that chapter.

As more people — mostly white people — found their R-1 paradise in Los Angeles, neighborhood after neighborhood, house after house decided to keep out the “undesirables,” meaning anyone not like the people living there. It didn’t really take burning crosses, although they appeared now and again.

No, something called “restrictive covenants” is all it took — language written into deeds to keep a piece of property from being bought by or sold to a non-Caucasian. Restrictive covenants were walls made of paper and ink.

To break down those paper walls took years of persistence. It took actresses and activists. It took courageous families and stubborn ones, and long, slogging decades through the courts and the voting booths.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

California entered the union in 1850 as a free state, not a slave state. For a long while, the percentage of Black Angelenos was low — about 2% in the 1910 census, peaking at above 11% around 1990.

Still, in 1913, the Black intellectual and writer W.E.B. Dubois brought the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People here and was impressed enough to say of L.A. that “nowhere in the United States is the Negro so well and beautifully housed.”

Yeah, well. Some exceptions applied.

A hundred or so California cities — among them Hawthorne and Glendale — were “sundown towns,” where Black people and sometimes other minorities dared not be found after dark, lest they be run out of town, run into jail or worse.

Also not for Black Angelenos: some of those darling Spanish houses or Craftsman bungalows along the city’s spreading edges. Restrictive covenants helped to ensure that the growing Black population was kept bottled up in many of the same neighborhoods of 1910, when the census showed that an astounding 36.1% of Black Angelenos owned their own homes.

Nat Laws was a babe in arms in 1910 when his parents, Henry and Anna, moved here. L.A. hadn’t changed for decades after the Laws family arrived, according to how Law described it to The Times almost 40 years ago: “Out in Hollywood and West Los Angeles, Negros couldn’t live in those neighborhoods. And Huntington Park? Man, a Negro couldn’t walk the streets in Huntington Park.” Signs on street corners in Huntington Park informed Black and Asian people that they were unwelcome, Laws said. “It was almost as bad in Culver City.”

In 1964, the Black writer Lynell George’s family went house hunting around Inglewood, and at the second house they stopped to see, someone down the street hollered the N-word at them. (At the first look-see appointment, the man who opened the door said he was too busy watching “Perry Mason,” and shut the door in their faces.)

This R-1 segregation was taken so much for granted that it was news in 1926 when a Black shipping clerk named Mentis Carrere bought a house in the 700 block of West 85th Street in Los Angeles. Feelings against him and his family, as The Times put it genteelly, “were aroused,” and so a white colleague named Harry Grund “became almost a bodyguard” for the Carrere family. One night, so the cops said, Grund fired off a pistol to make it seem like the Carreres were under attack. One bullet broke a window across the street, and, surprise, the very next day some high-pressure negotiations began to get Carrere to sell.

In 1917, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that governments couldn’t officially enforce racial segregation but wink-wink, nudge-nudge, the door was still wide open for private neighborhood segregation, one deed at a time — a “covenant” of agreement that, for sure, I won’t sell to any of those people, will you, Bob? No sir, not me; Tom, are you with us?

And that’s how it worked. Sometimes “those people” extended to Jews, or Asians, or Armenians, but first and last, they meant Black.

There followed more court decisions propping up segregation by redlining and other means. In 1928, California’s Supreme Court overruled two Los Angeles judges and said that a Black L.A. couple, A.D. and Mattie Kinchlow, could own the house in the restricted Crestmore neighborhood, on West 30th Street. They’d bought it from a white man who, as The Times put it, had “kicked over the traces” of the restrictive covenant to sell to them. But the judge also decreed that the Kinchlows could not live there. Our “Solomon” had officially halved the baby.

Downtown Los Angeles is but one ‘center’ of a city that grew out, rather than up. That was (mostly) on purpose.

It wasn’t until the end of World War II that L.A.’s restrictive covenants finally took a big kick in the pants, and thanks to some dauntless Black residents of a fine and fancy neighborhood they called Sugar Hill — a spot near USC named Adams Heights.

Same old, same old. Eight white neighbors brandished their restrictive covenant deeds and went to court. Let this continue, they shrilled, and their property “would lose value and racial clashes would inevitably ensue.”

But this time, their “objectionable” neighbors were more famous and probably richer than they, L.A.’s Black aristocrats, led by a formidable trio of Sugar Hill neighbors: the Oscar-winning actress Hattie McDaniel, actress Louise Beavers and blues singer Ethel Waters. They had the numbers, they had the money, and in the end, they had the law.

Superior Court Judge Thurmond Clarke had taken the time to take a look around Sugar Hill, and on Dec. 5, 1945, he made his decision: “It is time that members of the Negro race are accorded, without reservations or evasions, the full rights guaranteed them under the 14th Amendment to the Federal Constitution. Judges have been avoiding the real issue too long.”

So welcome home, Mesdames McDaniel, Beavers and Waters, et al.

What Clarke did in 1945, the U.S. Supreme Court reinforced in 1948, using the same 14th Amendment.

Quickly, and embarrassingly, a Los Angeles real estate organization joined other California real estate organizations in an effort to amend the U.S. Constitution to uphold covenants “to protect American family life, stabilize home values, avoid widespread home depreciation, avert racial tensions.”

When that went nowhere, they tried the same in California. Real estate interests put on the 1964 ballot an initiative to overturn the Rumford Act banning housing discrimination and to use the state Constitution to protect property bias.

I’m sorry to say that The Times endorsed it, and that Californians voted for it 2 to 1. But once again, the U.S. Supreme Court invoked the 14th Amendment to invalidate it, and in 1974, a different California electorate repealed it.

Housing bias still bubbled to the surface, like ugly globs in an oil spill.

A Black aerospace engineer named Kenneth C. Kelly had to use a white colleague as an intermediary to buy a house in a white neighborhood in Gardena, and again in 1962 when he moved to Northridge, where he became head of the Valley’s Fair Housing Council and encouraged other Black Angelenos to not to get deterred from buying the houses they wanted in the neighborhoods they wanted to live in.

After the 1965 Watts riots, The Times began looking more seriously at the realities for Black Angelenos, how they lived, and where. A Page One article in 1968 was headlined: “Negroes in White Suburbia: Few Problems Once Over the Barrier: Valley Negroes in Suburbia Finding Acceptance.” “Some 300 negro families,” the Fair Housing Council noted, have moved into middle-class white neighborhoods with “some early difficulties, but little outward hostility, no lowered real estate values or ostracizing of the negroes by their neighbors.”

In southeast L.A. County, white-flight fears after the Watts riots, and the disruptions from building the Century Freeway, altered the racial makeup of towns like Lynwood, Maywood and Huntington Park, where young Nat Law had once seen those racist signs. Unencumbered at last by restrictive covenants, Black people and Latinos bought and rented in neighborhoods that had once prohibited them. By 1972, the theretofore white town of Compton was 71% Black.

An unnamed retired white industrial worker in Compton told The Times then that white people were “in a sweat” to sell and move out — not because of Latinos, he made a point of saying, but because of Black people.

Restrictive covenants kept a kind of power — as a tripwire. President Reagan found out the hard way, publicly, a month before election day 1984 — that some property he’d once owned in the Hollywood Hills during World War II carried fine-print language declaring that “no persons of any race other than the Caucasian race” could use or occupy that property, except as servants.

In 1994, Sen. Dianne Feinstein was embarrassed in her reelection. Hours after she accused her opponent of having restricted-covenant language in property he’d owned, she learned that her own property was saddled with the same language dating to 1909.

Restrictive covenants still have a long and shadowy reach in Los Angeles. The city was and in many places is still deeply and de facto segregated.

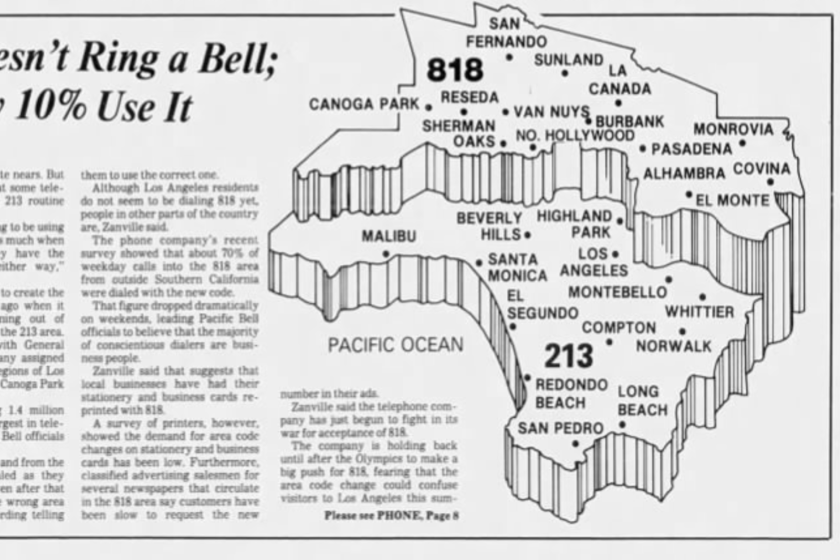

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

For me, an incident that revealed that clearly — and ultimately violently — was this:

In May 1974, when the Black leader of the radical revolutionary Symbionese Liberation Army group brought his white “soldiers” and his hostage-or-follower, the heiress Patricia Hearst, to Los Angeles, he made the basic, fatal error of not doing his recon.

In the SLA’s old Bay Area stomping grounds, his group of mixed-race men and women moving around in a working-class neighborhood would likely not have been remarked on.

But the comings and goings of six or eight young white women and men in a Black neighborhood of South L.A. — especially white people with guns — got the locals’ attention.

The Los Angeles Police Department found out where the SLA was hiding when a woman went up to a traffic cop and asked whether the police “were looking for the white people with the bullets and guns.”

They were in her daughter’s house on East 54th Street. The hours-long gunfight that followed was broadcast live on TV, and it ended with six dead SLA members in the little house that burned down to the crawl space.

Judging by the wisdom of the internet, where that house once stood is now a pretty duplex fronted by a thicket of semitropical plants. Also judging by the internet, the place one or two doors down, another apartment, has a price tag floating around three-quarters of a million.

Maybe equity is the best revenge.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.