Diane Norman lost her memory twice.

The first time, it disappeared in bits and pieces. She forgot where she left her purse, searching for it dozens of times a day. She forgot how to cook and how to pay the bills. She forgot people who were fixtures in her life.

Then, last year, she lost it again when the pandemic kept her away from her husband — the keeper of her memories.

“Today is our wedding anniversary,” Gordon Norman said, as he sat in the living room beside the chair his wife once occupied in their Glendora home. It was Feb. 17, a Wednesday, and they were celebrating 54 years of marriage — over FaceTime.

“No,” she exclaimed.

“Yes,” he told her. “Do you remember you had all that rice in your hair and you had a bun on and we shook rice out of your hair for days?”

“Do you remember the beautiful dress you had when you got married and how handsome I was?”

Do you remember?

Diane, who could once answer every question on “Wheel of Fortune” and “Jeopardy!,” didn’t have the answers this time. Her husband knew the details of her life better than she did.

Almost a year has passed since Gordon last saw Diane in person. The 80-year-old woman — diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease nearly four years ago — went into an assisted living home last April, during a nationwide shutdown.

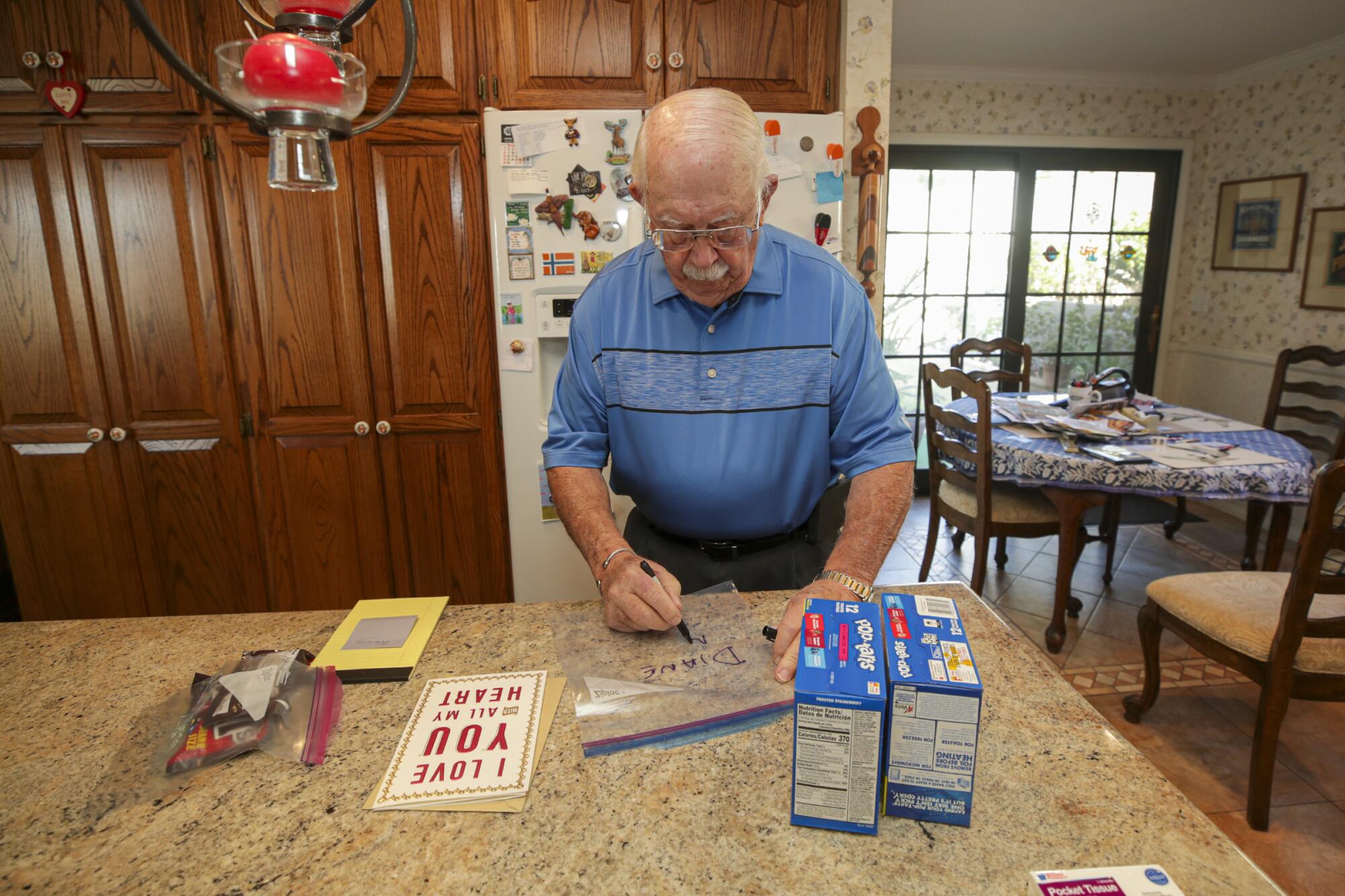

The closest Gordon gets to her now is the front step of the small residential home in the San Gabriel Valley, where he drops off medicine, diapers, Pop-Tarts and cards addressed to his “Princess Di.” He fears that being so close but separated from her by a pane of glass would only confuse her.

Throughout the country, family members have gone nearly a year without seeing loved ones who are in care facilities. In an effort to contain the pandemic, most such places do not allow visitors. It’s a constant topic of conversation in the Alzheimer’s Assn. support groups.

The disease, which steals memory and has no cure, already upends lives; coronavirus precautions only make difficult lives harder.

Like many other spouses and family members, Gordon gets by on the hope he’ll be reunited with the woman he loves in the post-vaccine world.

“When are you coming home?” Diane asked, her hair pulled back like the day they wed. Back then, it was short and dark blond, her face smooth. Now, her hair has turned gray and hangs past her shoulders. Age had made lines flow across her cheeks like tributaries.

Gordon’s words betrayed the uncertainty of the world around them.

“Some day real soon, maybe in the next month, when we all have the vaccine in our body and are safe, I’m going to possibly have the opportunity to come into the house and see you in person.”

Her face broke into a wide grin.

“When you marry, you never know what’s down the road,” Gordon said later. “You take it, good or bad.”

Gordon was a band director at Glendale High School. Diane was married to the school’s head football coach; they had two small children. Diane was widowed soon after the school year ended in 1966, when a woman ran a traffic light and crashed into her and her husband’s Volkswagen Beetle.

It wasn’t until months later, after Gordon invited his niece and Diane’s daughter to do a baton-twirling number during one of the school’s halftime shows, that the two got to know each other better.

Diane, Gordon recalled, “was drop-dead gorgeous.”

“They say when the right one comes along, it hits you like a freight train,” Gordon said with a chuckle. “I guess that’s what happened.”

Within months, he proposed.

They were married on Feb. 17, 1967, a Friday. Her dress was pink, his tuxedo maroon. Her bridesmaids were her younger sisters, Linda and Patsy, and Gordon’s younger sister, Sandra. A photo of that day, of the smiling newlyweds holding hands, hangs in the house where they raised their three children.

They were always a team. First, when Gordon worked as a band director at Glendora High School and later Cal State Long Beach, and his students were selected to perform in the Rose Parade a handful of times. Then later, when they opened up a travel agency, specializing in accommodations for bands and musical groups. The couple worked 70 to 80 hours a week.

“The whole time, she was right there by him,” said Bob Kuhn, a former mayor of Glendora and the executor of the family’s estate. “He couldn’t have done it without her and she couldn’t have done it without him.”

They were pillars of the community. She served as president of the PTA council and of the Kiwanis Club, and served on the Glendora Planning Commission. He was past president of the Rotary Club, served on the Parks and Recreation Committee and was the co-founder and president of Glendora’s Sister Cities program with Moka, Japan.

A wall in their home is a testament to their service. A plaque touts them as Glendora’s “2008 Citizens of the Year.” Hundreds of people came to the banquet in their honor.

In a profile of the couple, the Glendoran Magazine quoted residents who described Diane as the “behind the scenes person, always there to help make sure Gordie has what he needs, no matter what project he has undertaken.”

Gordon first noticed Diane’s memory slips while on a weeklong trip to his hometown of Fosston, Minn. Diane kept forgetting her purse and wallet and was quiet among people she knew.

“I just sort of watched the progression go down,” Gordon recalled. In June 2017, her doctor referred her to a specialist for evaluation. They had planned a trip that summer, but the next month the neurologist recommended she cancel, “because of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Then, a year ago, Gordon watched everything slide further. Diane sat in a chair rambling to herself. Sometimes she swore at him.

He grew scared one day when he came home and she wasn’t there. For the next hour, he called everyone he could think of. She had walked a mile to the pharmacy in downtown Glendora.

“But she came home,” he said. “That was a blessing.”

In March of last year, Gordon saw his world shift twice. First, as the pandemic prompted local leaders and the governor to declare a state of emergency and begin locking down. Then, a second time, when Gordon sat down with his two sons and made the difficult decision to put Diane into a care facility.

They placed her in a home on a Tuesday morning; by the next day the staff told Gordon he had to pick her up. They told him she was “disruptive and abusive.” He brought her back home.

“I did everything in the world to try to calm her down,” he said. Nothing worked. At one point, Diane pushed a shoe box down the hall with her nose.

Scared, Gordon called 911, and his wife was placed in a behavioral health hospital for three weeks.

The last time he saw her in person was April 3. That same month, she was transferred into a home that cares for elderly residents with dementia. No one was allowed in or out, which kept the virus at bay.

For Gordon, the first three months were the hardest.

He tried to keep busy, cleaning out the house and donating to the secondhand store. His former Glendora band students looked after him, bringing him food and baked goods.

“It took me a lot of mental training to not wonder what she was doing each minute,” Gordon said. “I go to bed every night knowing she’s in a safe place, that there’s a good staff and she’s being taken care of.”

But the pandemic only deepened Gordon’s pain and loneliness.

On Valentine’s Day, he shuffled across the driveway, his back stooped with age. In one hand he carried a bouquet of roses, a box of chocolates and an envelope that read “Princess Di.” In the other was a pack of Assurance diapers.

He laid them carefully beside the welcome mat, which was at odds with the sign tacked up beside the front door: “To protect our residents, staff, and communities we serve, we are requesting no visitors during this time (COVID-19).”

From there, he drove 50 feet up the street and called the home like he did every week.

“Yes, good morning, this is Mr. Norman,” he said. “It’s a Happy Valentine’s Day … there’s a delivery outside the door.”

Back home, seated in the kitchen, Gordon reminded his wife what day it was. Diane, once a beautiful dresser, wore a red Christmas sweater with snowflakes and a snowman. Over the last year she had lost about 10 pounds and the lines in her face had grown more pronounced.

“Give me a smile, give me a smile,” Gordon coaxed. “Valentine’s Day, we say, ‘I love you.’”

It now cost to see a smile from Diane. He didn’t get one that day. But before they hung up, she said the words he hoped to hear: “I love you, babe.”

He tries to FaceTime her at least every other day. Sometimes it’s a one-sided conversation or the seconds pass in silence. She didn’t register when Gordon told her a friend had passed away. She couldn’t celebrate when her daughter’s scans showed no sign of cancer.

On their anniversary, he told her about their grandkids. Taylor had gotten so tall. They were struggling with online school. He asked if she’d heard from their daughter, if Diane knew who she was.

He reminded her again who he was: “Gordon. My name is Gordon.”

Despite it all, he held on to the hope of being with her soon. He had recently gotten his second vaccine dose. She would get hers the day after their anniversary.

Then, last week, Gordon got a call.

His wife had fallen at the home and fractured her hip. The hospital called and asked — if her heart stopped in surgery, should they resuscitate? Instead of a reunion, he was thinking about whether his wife would die on the table.

They had decided a decade ago that they wanted “no heroics.”

“We’ve had enough life experiences to know we don’t want to have anyone have to agonize over making the decision,” Gordon said. But when he brought her advance directive — with a do-not-resuscitate order — to the hospital, he was devastated.

It was days before Gordon was able to FaceTime and comfort Diane. She had to be moved to a rehab center for at least a week. When she returned to the home, she would need to be quarantined for two more weeks.

“They keep kicking the ball farther down the road every day,” he said.

Still, he holds on to the hope that he’ll get to see her, the woman he fell in love with over half a century ago. Even if she doesn’t know who he is, that’s OK. He’ll know who she is.

His Princess Di.

Times staff photographer Irfan Khan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.