Some healthcare workers refuse to take COVID-19 vaccine, even with priority access

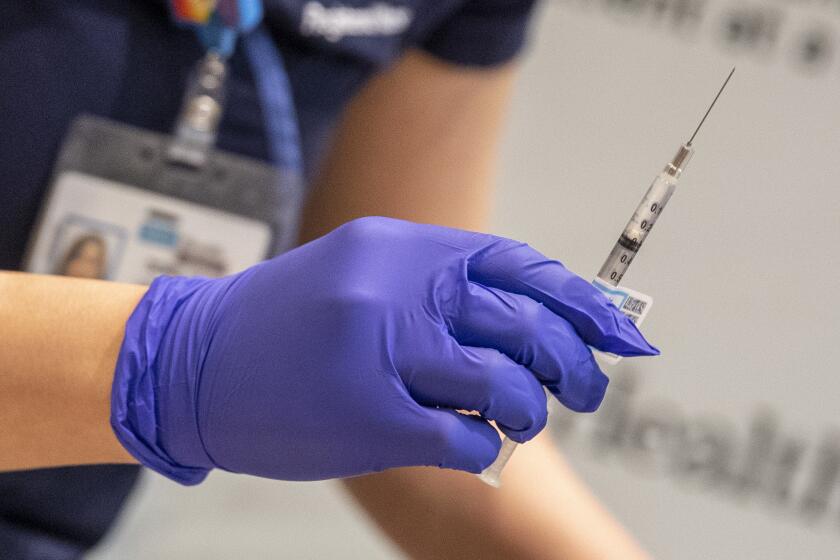

They are frontline workers with top-priority access to the COVID-19 vaccine, but they are refusing to take it.

At St. Elizabeth Community Hospital in Tehama County, fewer than half of the 700 hospital workers eligible for the vaccine were willing to take the shot when it was first offered. At Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, one in five frontline nurses and doctors have declined the shot. Roughly 20% to 40% of L.A. County’s frontline workers who were offered the vaccine did the same, according to county public health officials.

So many frontline workers in Riverside County have refused the vaccine — an estimated 50% — that hospital and public officials met to strategize how best to distribute the unused doses, Public Health Director Kim Saruwatari said.

The vaccine doubts swirling among healthcare workers across the country come as a surprise to researchers, who assumed hospital staff would be among those most in tune with the scientific data backing the vaccines.

The scientific evidence is clear regarding the safety and efficacy of the vaccines after trials involving tens of thousands of participants, including elderly people and those with chronic health conditions. The shots are recommended for everyone except those who have had a severe allergic reaction to any of the ingredients.

Still, skepticism remains.

April Lu, a 31-year-old nurse at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center, said she refused to take the vaccine because she was not convinced it was safe for pregnant women. She is six months pregnant.

Clinical trials have yet to be conducted on pregnant women who take the vaccine, but experts believe the vaccine is unlikely to pose a specific risk, according to the Centers for Disease Control. The agency says pregnant women may choose to be vaccinated.

“I’m choosing the risk — the risk of having COVID, or the risk of the unknown of the vaccine,” Lu said. “I think I’m choosing the risk of COVID. I can control that and prevent it a little by wearing masks, although not 100% for sure.”

Some of her co-workers have also declined to take the vaccine because they’ve gone months without contracting the virus and believe they have a good chance of surviving it, she said. “I feel people think, ‘I can still make it until this ends without getting the vaccine,’” she said.

The extent to which healthcare workers are refusing the vaccine is unclear, but reports of lower-than-expected participation rates are emerging around the country, raising concerns for epidemiologists who say the public health implications could be disastrous.

A recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 29% of healthcare workers were “vaccine hesitant,” a figure slightly higher than the percentage of the general population, 27%.

“Even the name, Operation Warp Speed, draws some concern for people about the rush to push it through,” said Dr. Medell Briggs-Malonson, an emergency medicine physician at UCLA Health who has received the vaccine. Still, she urged her colleagues to do the same.

“It’s certainly disappointing,” said Sal Rosselli, the president of the National Union of Healthcare Workers. “But it’s not shocking, given what the federal administration has done over the past 10 months. ... Trust science. It’s about science, and reality, and what’s right.”

The consequences are potentially dire: If too few people are vaccinated, the pandemic will stretch on indefinitely, leading to future surges, excessive strain on the healthcare system and ongoing economic fallout.

“Our ability as a society to get back to a higher level of functioning depends on having as many people protected as possible,” said Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch.

Respondents to the Kaiser Family Foundation survey who said they probably wouldn’t get the vaccine said they worried about side effects; they lacked trust in the government to ensure the vaccines were safe; they had concerns about the role of politics in the development of the vaccines; or they believed the dangers of COVID-19 had been exaggerated.

In online forums, some healthcare workers throughout the country have expressed frustration over going first — a status some have associated with experimentation.

Nicholas Ruiz, an office assistant at Natividad Medical Center in Salinas, Calif., said healthcare workers wrestled with the same doubts, fears and misinformation about the disease as the public. Though he interacts with nurses who treat COVID-19 patients, he’s not taking it and knows many others who aren’t.

“I feel like the perception of the public with healthcare workers is incorrect. They might think we’re all informed of all of this. They might think that because we work in this environment,” Ruiz said. “But I know there’s a lot of people that have the same mentality as the public where they’re still afraid of getting it.”

In Fresno County, interim Public Health Officer Dr. Rais Vohra said Tuesday that some “people who are qualified to get the vaccine are not ready to get it.” Such healthcare workers, including those who are pregnant or want to become pregnant, have been hesitant as questions about the long-term effects arise.

To persuade reluctant workers, many hospitals are using instructional videos and interactive webinars showing staff getting vaccinated. At an Orange County hospital, Anthony Wilkinson, an intensive care nurse who cares for coronavirus patients, said he had co-workers who had “lost faith in big pharma and even the CDC.”

Wilkinson made a Facebook video about the science behind the vaccine and was updating friends and family on his progress after receiving it. “People are scared for me,” he said. “I can understand why. It’s new and no one wants to be the first.”

The first allocations of the vaccine made by Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech arrived last week in Tehama County, home to 65,000 people.

Dr. Richard Wickenheiser, the Tehama County health officer, said 495 doses were first made available to healthcare workers at St. Elizabeth Community Hospital in Red Bluff, but the hospital “basically returned 200 back to us.”

“They gave us those vaccines back, and we quickly started moving it out and using it,” Wickenheiser said. “I don’t want to be accused of having it in the freezer while we wait for people to make up their mind.”

At Laguna Honda Hospital in San Francisco, about 10% of the nursing staff has opted out of the vaccine, said spokeswoman Zoe Harris.

As of Tuesday, UCLA Health had vaccinated 7,300 personnel out of more than 37,000, though it wasn’t clear how many people had been offered the vaccine because the hospital didn’t release that information. Officials acknowledged that “there may be vaccine hesitancy in our workforce.”

“We are not asking personnel to decide immediately whether to receive the vaccine. We want to give those offered vaccines adequate time to make a decision, and we hope that personnel will continue to understand that the benefits of vaccination clearly outweigh the risks,” the hospital said in a statement.

The uncertainty is shared among staff inside nursing homes, which account for roughly 35% of the more than 25,000 COVID-19 deaths in California.

But about a quarter of the staffers have voiced reluctance to take the vaccine, said nursing home administrators and employees interviewed by The Times.

“They’re scared of the side effects, they don’t know what is going to happen or if it will really protect them,” said a licensed vocational nurse at a Los Angeles nursing home who asked that her name not be used because she was not authorized to speak to the media. “It has become so political.”

She was reluctant to take the vaccine herself until the 95-bed facility she works in, which had been virus-free for months, was hit by the rapid community spread. “We have 16 new cases in just three days,” she said. “It’s so fast, we don’t even know how it happens.”

“Reluctance? No question, there’s a lot of reluctance,” said Dr. Michael Wasserman, medical director of the Eisenberg Village nursing home in Reseda and past president of the California Assn. of Long Term Care Medicine, which represents doctors, nurses and others working in nursing homes.

“Because there was no transparency or clarity from the federal government with the rollout, the states and the counties often didn’t know what was happening until the last minute,” he said. “That makes the vaccine reluctance even worse.”

It’s unclear what happens when a hospital ends up with extra doses. State guidance allows hospitals to offer the vaccine to lower-priority people if frontline workers have already been offered the vaccine.

In Tehama County, unused doses at hospitals are being distributed to the next group of people who are eligible: staff and residents of assisted living and skilled nursing facilities.

Meanwhile, the county’s health department is fielding daily phone calls about access, said Wickenheiser, the Tehama County health officer, adding, “The public is asking on a daily basis: ‘When are we going to get it?’”

Times staff writers Laura Newberry and Jaclyn Cosgrove and staff photojournalist Francine Orr contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.