As more L.A. County Black and Latino men get the COVID-19 vaccine, distrust lingers

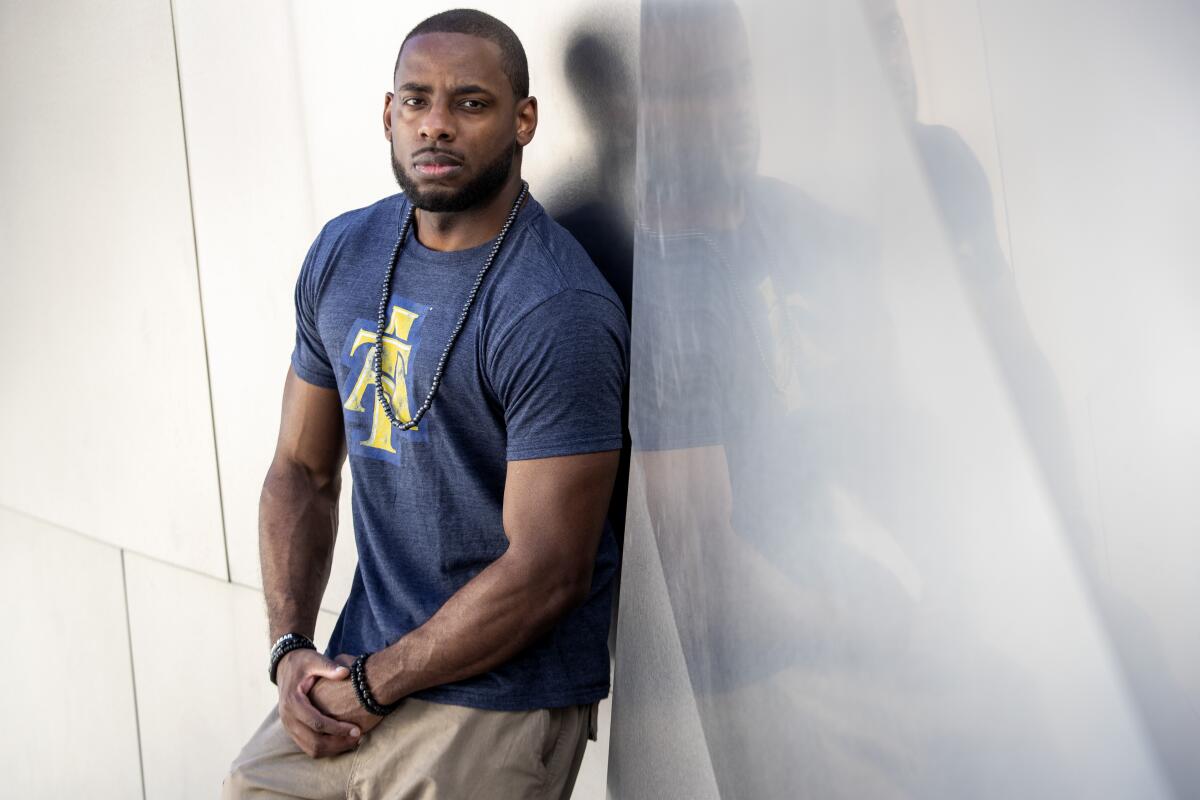

Drew Bullock has heard the same concerns over and over from men unsure about COVID-19 vaccines.

Concerns about possible risk to their immune systems and over how fast the vaccines were developed. Concerns referencing the Tuskegee experiment, when treatment for syphilis was withheld from hundreds of Black men in Alabama.

“I think when it comes to specifically Black men and our distrust in the medical industry, by not getting vaccinated we’re causing a Tuskegee 2.0,” Bullock said.

Aiming to be “funny but accurate,” he decided to combat the misinformation and outright falsehoods that he found so alarming on social media by turning his YouTube page — which has 26,000 subscribers — into a source for vaccine skeptics.

After an extremely slow start, Los Angeles County in recent months has made significant progress in vaccination rates among Black and Latino males age 12 and older. Between May 9 and Oct. 24, the most recent data available, the percentage of vaccinated Black males in those age groups rose from 36% to 54% and from 39% to 60.8% among Latinos in the same groups.

Black males continue to have the lowest vaccination rate in the county across race and gender. Just 39% in the 18-29 age group have had at least one dose of the vaccine; for Latino men the figure is 52%.

The situation is becoming more urgent as public health officials anticipate yet another coronavirus surge when racial and ethnic disparities often worsen.

Public health workers fear Black and Latino men will continue waiting to get vaccinated until they almost die from COVID-19 or watch people they know die. Men of color say this mistrust arises from their frustration that they only get public health officials’ attention in times of crisis.

“It’s a sad state of affairs where the government agencies that are really responsible for helping us all be safe cannot be trusted,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said in a news briefing last week. “We all have to own part of the reason why that feeling is so prevalent, and the best way to do that is to go about fixing it, and being present and making sure that people do have the resources they need to be healthy.”

That means answering people’s questions as long as it takes, Ferrer said, as well as setting up convenient vaccine sites, knocking on doors and working with trusted community organizations.

County and community workers have gone to swap meets, produce markets, churches, soccer fields, Home Depot and auto parts stores. Men of color who are doctors or public health workers have also been present to address concerns about whether the vaccine can affect virility and fertility.

The county has moved vaccine clinics and informational events to after-work hours and stopped assuming everyone has a primary care doctor they can speak with about the vaccine.

Tracey Veal, a public health worker with the county who focuses on community vaccine distribution, said some men of color are uncomfortable in traditional healthcare or governmental settings because of how they may be perceived, be it for their tattoos or because they once were incarcerated.

The information and misinformation some men are receiving is often from family and friends. Veal said “vaccine warriors on the ground” are essential.

“If one of the leaders in that pack gets questions answered to a sufficient degree, it’s kind of like a pack mentality,” Veal said.

Veal said she has seen people show up to the county’s events with lists of home regimens they say are helping them ward off COVID-19, such as taking vitamin C gummies, Emergen-C powder packets, vitamin D, zinc, cannabidiol oil, known as CBD, coconut oil or the herb echinacea.

“The fact that people have bought into the idea that vitamins are like medicine, that they actually equate it … to a vaccine, tells me that there’s not enough information” being shared in the community, Veal said. “The fact that people think they’re healthy enough, that doing that is sufficient, it’s actually frightening to me in some ways.”

Keith Parker said he got vaccinated months ago because he “wouldn’t be able to live with himself” if he passed on the virus to his 82-year-old mother. But even as director of Project Fatherhood — an initiative supporting dads in Los Angeles — he doesn’t want to pressure men in the group to get vaccinated.

The organization has brought in public health experts to address concerns men have about the short period of time it took to create the vaccines, the side effects and what’s in them.

“It takes time to build trust in our communities; you can’t only come to us when you need something from us,” Parker said. “You have to listen to what our needs are.”

Bullock said he was initially motivated to get vaccinated to protect himself and his parents, who are in their mid-60s. He also wanted to go back to the clubs, parties and his alma mater North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University‘s homecoming, branded online as the “greatest homecoming on Earth.”

“Even with the conversation I’ve had on Clubhouse to get people understanding about how the vaccine works, they say, ‘Yo, I’ve never had anyone explain it to me like that. OK, I’m going to get it,’” Bullock said.

He has posted YouTube videos on why he got vaccinated, the long-term effects of COVID-19 and a response to unvaccinated NBA players. He also shares videos and responds to questions on Twitter.

Bullock said he has lost count of how many people have tweeted or sent him messages saying they or their children got vaccinated after seeing his videos.

But he remembers the two times he had an asthma attack and couldn’t breathe. Hearing how COVID-19 affects breathing made Bullock realize the virus was unlike the flu or common cold. Most of his friends received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, but several others are still unvaccinated.

“I’m a regular dude from around the way who did research,” Bullock said. “I’m able to understand what the fear and struggles are and sometimes it’s a good conversation to have and say, ‘Nah, this is what it is, bro.’ I think it really takes understanding how dangerous this virus is, particularly to us as Black men.”

Dr. Efrain Talamantes, chief operating officer of AltaMed Health Services, which runs community clinics throughout Los Angeles and Orange counties, said many of the young men he’s spoken with about vaccines “do not see COVID-19 as an immediate threat to their lives.”

Some still think it’s fatal mostly for older adults or people with chronic health issues, he said, and health workers need to find better ways to describe to young men what COVID-19 is capable of without seeming to stigmatize or blame them.

“There is an [idea of] masculinity that in some ways healthcare has perpetuated, but I do know that in talking to some of our patients that are young men, they want to have a place in knowing that they can come to healthcare and it’s not like a surprise or a bad thing,” Talamantes said. “They want to be included in a more holistic, healthy approach similar to what we do with women, and I’m not sure we’ve done enough.”

In Koreatown, Jose De Leon and his wife stopped going out with their three children when COVID-19 hit last year except for food and walks outside with masks on. Back in the car everyone uses hand sanitizer, and when they return home they remove their clothes and put them in a bag until they can be washed.

But De Leon does not want to get vaccinated.

“You still have the chance of getting it, it doesn’t matter if you’re vaccinated or not,” De Leon said. “I think it’s how you take care of yourself and how safe you are and careful you are around others.”

His wife got COVID-19 after being vaccinated for her job. He has had multiple friends get COVID-19. A friend’s stepfather died from the virus. He remembered when his mother and aunt got COVID-19 and all the family could do was drop off Pedialyte and protein milkshakes at their doorstep for two weeks.

But amid being “kind of scared” of needles, his distrust in the vaccine, fear of experiencing vaccine-related complications and seeing other people recover from COVID-19, De Leon said he does not plan to get the vaccine until required.

“I’ve been around people who had COVID and I haven’t gotten it,” De Leon said. “When I do get [COVID], I’ll get it. I’m not scared.”

While the vaccine does not guarantee someone will not get COVID-19, county public health experts recently noted unvaccinated people are seven times more likely to get infected and 27 times more likely to be hospitalized than those who have gotten the shot.

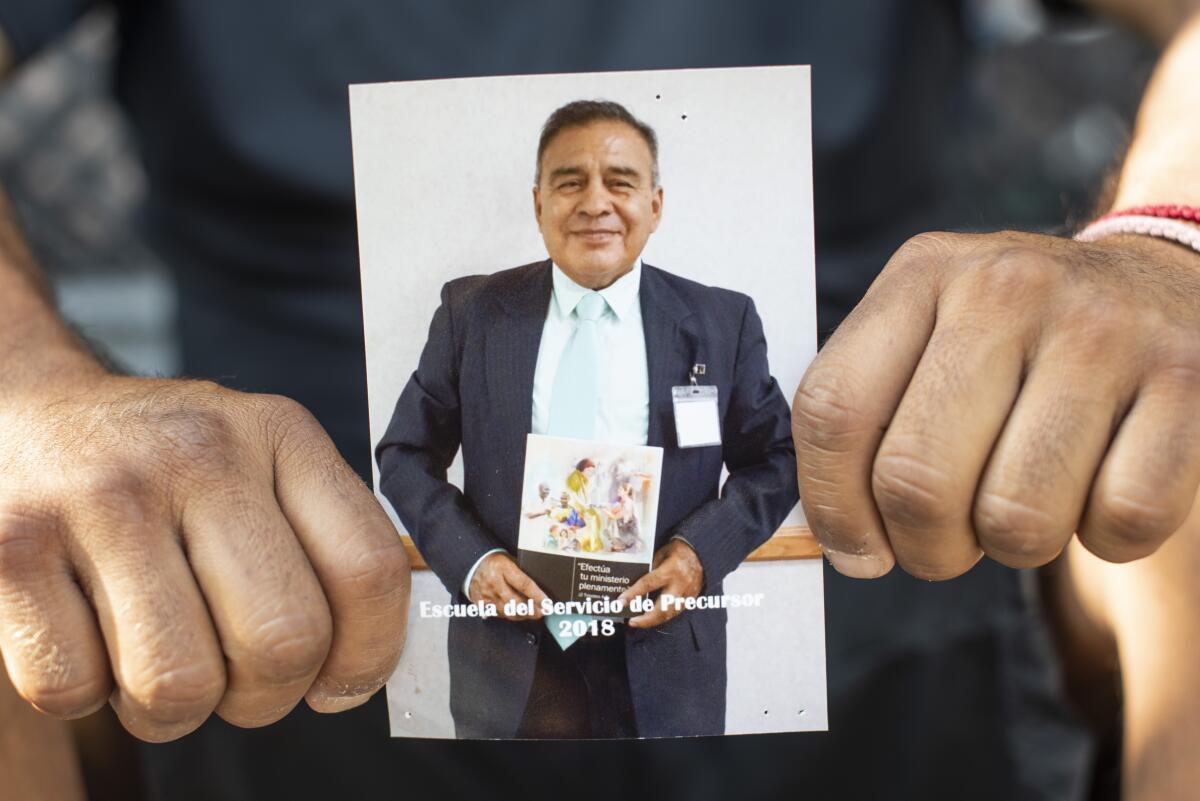

When Jaime Samano received his first dose in March, he thought about his father.

Samano’s parents, both diabetic, had mostly stayed home since early in the pandemic, washing their hands and wearing masks. His father, born in Mexico, was a caring man and “an example of a dad anybody can ask for.” He was looking forward to getting vaccinated, Samano said, but died two weeks after getting COVID-19, on Jan. 2. He was 70.

For Samano, he asked himself: If the vaccine was going to help him even a little bit, why not get it?

“I was thinking in a way what happened to my dad, and me working out in the field too, I’m a high risk and exposed to getting [COVID-19] so I do want to get it as soon as I can,” Samano said.

Samano said talking to Talamantes, who is his doctor, and his wife, who also works in the healthcare industry, reassured him about the vaccine’s safety. Most of his family, including his brothers and his mother, are vaccinated too. When talking to friends, he encourages them to do the same.

He still hears from unvaccinated people who say they’re not going to get it until their job requires it, they don’t know what’s in the vaccine and even that it’s a trick from the government.

“I never thought, ‘Well, if it’s a trick, the government is going to control me,’” Samano said. “To me, that’s a bunch of nonsense.”

Times staff writer Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.