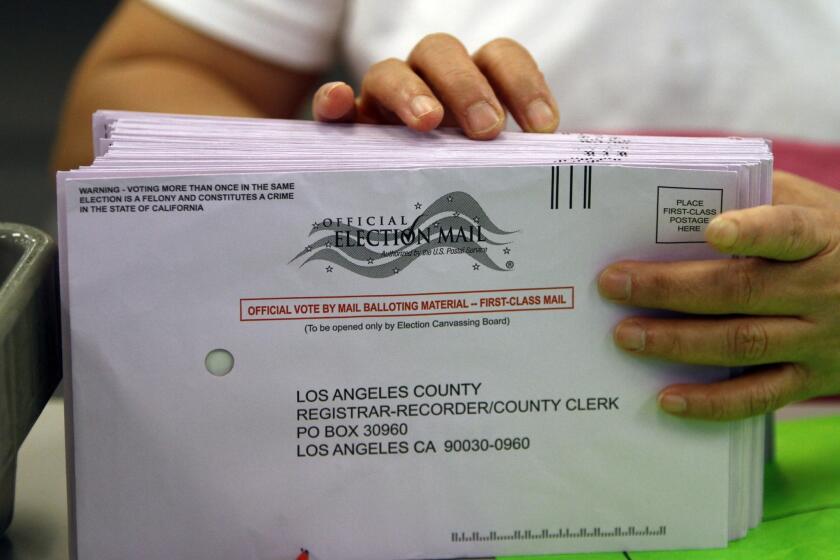

Mail-in ballots flagged for rejection hit 21,000; Black, Latino voters rejected at higher rate

In Nevada, about 4,000 votes cast by mail so far won’t be counted unless voters can explain discrepancies between their ballot signatures and registration forms.

In Florida, the same is true for nearly 4,000 voters in three populous counties.

And in North Carolina, nearly 8,000 mail-in ballots have been flagged for rejection, many because they lack a witness signature.

As electoral workers begin processing votes across the country this election day, more than 60 million will be mail-in ballots that can be rejected if they have not been properly submitted. The rejection rate reached 1.4% in the 2018 general election and 1% in 2016, which proved decisive in some close races.

An early snapshot of rejection rates reported thus far in Nevada, Florida, North Carolina and other battleground states show a mixed picture: Although overall rejection rates are generally lower than in past elections, the votes of Black people and Latinos are being rejected at higher rates than those of white Americans.

Election 2020: These states will probably decide if Joe Biden or President Trump wins the race. And their absentee ballot laws could determine when we find out.

The mail-in voting system has never been tested on such a massive scale, leaving open the possibility that some mail-in voters could be disenfranchised because of mistakes on their ballots. Those errors can include failing to sign the ballot, or signing in a style that doesn’t match what’s on the voter’s registration forms or driver’s license. In some competitive races, those challenged votes could play a deciding role.

More than 21,000 mail-in ballots thus far have been slated for disqualification in battleground states that have begun processing and reporting ballots, according to a Los Angeles Times analysis of data from election officials and the U.S. Elections Project.

The data on disqualified ballots is incomplete and could change as voters correct, or “cure,” ballots slated for rejection. In six of the eight swing states analyzed by The Times, the law requires elections officials to notify voters of perceived errors and give them a chance to cure their ballots.

There is one positive sign in the early ballot data: The rate of ballots that have been challenged or disqualified by elections officials so far this year is lower — in some places, significantly — than in the 2018 midterms or the 2016 presidential election, according to the Times’ analysis.

“By and large, voting is proceeding smoothly,” said Bob Bauer, a legal advisor for former Vice President Joe Biden’s presidential campaign. “The rejection rates of ballots are falling well below what many believed would be the case.”

Early numbers from North Carolina and Georgia show Black and Latino voters are roughly three times as likely to have their ballots rejected as white voters, according to data from the U.S. Elections Project.

That aligns with a disturbing pattern from past elections where Black and Latino voters’ mail-in votes were disqualified at higher rates. A study of the 2018 general election in Florida found ballots cast by Black, Latino and other non-white voters were discarded at more than twice the rate of their white peers.

Three generations of a Las Vegas family tell how it feels to be a Black man in America in a season of protest.

The screening of mail-in ballots in many states can be prone to human error. That’s because election officials have to verify that the signature on a ballot envelope matches the one on a voter’s driver license or voter registration card. In some jurisdictions, workers with little to no training in handwriting analysis use their own eyes to verify a signature in as little as five seconds.

In the 2016 presidential election, mismatched signatures were the leading cause of rejection for mail-in ballots, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, which surveys voting municipalities to document elections.

Rejection rates vary widely by state, with New York, Arkansas and Kentucky leading the nation in 2018. California was in the middle of the pack. About 161,000 out of its 8.2 million mail ballots were rejected in 2018, or 2%.

Until recently, voters in many states didn’t have the opportunity to cure ballots. But a wave of new laws and legal settlements over the last two years have created new processes in a dozen states, including Florida, Virginia, Michigan and North Dakota, to notify voters of problems and give them a chance to correct them.

In California, voters have the chance to correct problems with their signatures until Dec. 1, the latest deadline in the country.

Palms resident Sydney Ganon, 31, and her husband put their ballots in an official drop box almost a month ago. Then she checked the status of the ballots online and saw that his had been accepted, but hers had not.

An election official told her that the ballot had been flagged for a perceived signature mismatch. It was the first time she had voted by mail, she said, and she didn’t know that they would check her ballot envelope signature against her driver’s license.

“I did a very careful, legible signature, which must have set off a red flag somewhere,” Ganon said. “My normal writing is pretty scribbly.”

Thankfully, she said, the process to correct the problem was simple: She filled out a one-page affidavit and returned it by email.

That opportunity to correct ballots doesn’t exist in many states, including a handful of battleground states where President Trump narrowly eked out victories in 2016. They include Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where the bulk of the ballot processing cannot begin until election day, and where officials are not required to provide a cure process.

Rejection rates have been far higher than the national average in large counties in swing states North Carolina and Pennsylvania. In the Philadelphia suburb of Montgomery County, for example, some 8% of mail ballots have been rejected so far. Wake County, N.C., home to the capital, Raleigh, has a 4% rejection rate.

Miami-Dade County, the biggest county in Florida, has received nearly 490,000 mail-in ballots and has put aside almost 2,600 with missing signatures, mismatched signatures and other issues, said Roberto Rodriguez, spokesman for the county supervisor of elections. More than 2,500 voters have also corrected issues with their ballots, meaning their votes will be counted, he said.

In Hillsborough County, the fourth-biggest county in Florida and home to Tampa, a team of elections workers are working to contact the 1,009 voters whose mail-in ballots have already been flagged for a perceived signature mismatch, said Gerri Kramer, a spokeswoman for the supervisor of elections.

A little more than half of the flagged signatures have been cured and will be counted, Kramer said. The remaining 463 voters whose ballots were flagged have until 5 p.m. Nov. 5 to fix the issue, she said.

Each voter will receive a letter notifying them of a problem with their ballot, Kramer said. Elections workers are calling and emailing voters if they have provided that contact information, she said.

Election 2020: When will we know if Biden or Trump wins? What happens if Trump says he won while votes are still being counted? What’s a ‘red mirage’?

In Washoe County, Nev., the elections office is “busting at the seams,” with one of its conference rooms stuffed with 300 boxes of voting materials, said Heather Carmen, the assistant registrar of voters.

But Carmen said she was confident that the 650 or so voters whose ballots had signature mismatches in her county would get a chance to prove their identities. In addition to alerting voters by mail, election workers are calling and sending emails to voters to notify them of any problems with their ballots. Voters are then required to send in a photocopy of a government-issued ID by Nov. 12.

The county, home to Reno, has received 118,000 mail-in ballots, with 84,000 already tabulated.

“We are definitely working long hours to get them all processed,” she said.

Times staff writer Evan Halper contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.