Mail-in ballots are pouring in by the millions to election offices across the country, getting stacked and prepared for processing. But before the count comes the signature test.

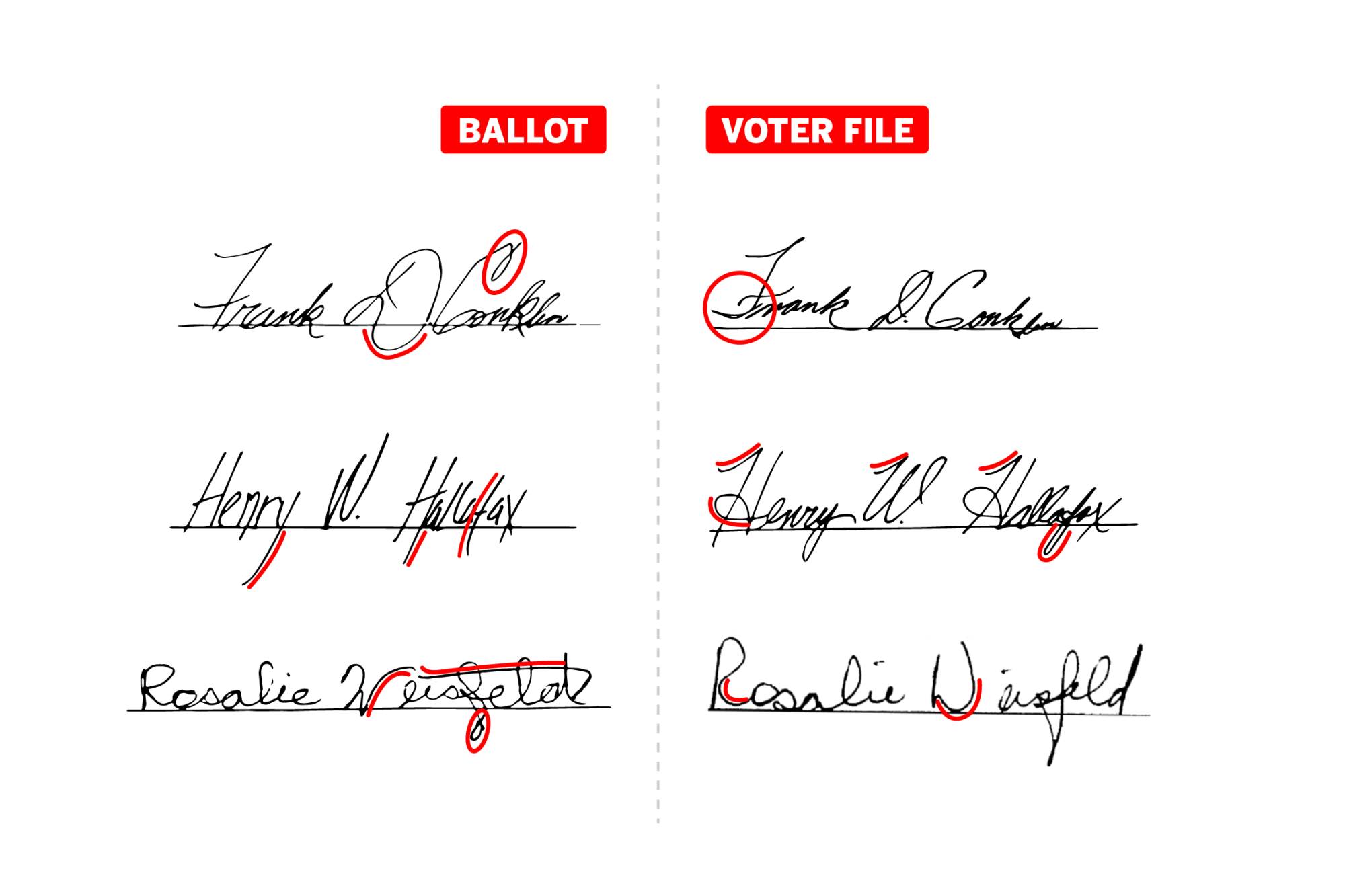

Election workers eyeball voter signatures on ballots one by one, comparing the loop of an “L” or the squiggle of an “S” against other samples of that person’s writing.

When performed by professionals in criminal cases or legal proceedings, signature verification can take hours. But election employees in many states must do the job in as little as five seconds.

In an election marked by uncertainty amid the pandemic, the signature verification process represents one of the biggest unknowns: whether a system riddled with vulnerabilities will work on such a massive scale.

In 2016, mismatched signatures were the most common reason that mail ballots were rejected, according to federal officials. With record numbers of people voting by mail this cycle, ballots thrown out for signature problems and other issues have the potential to decide races where the margin of victory is slim.

Candidates could mount legal battles over the verification process to challenge election outcomes. President Trump has repeatedly asserted, with no evidence, that mail-in voting is rife with fraud.

Rejected mail-in ballots have been a significant factor in recent elections.

This year a New York congresswoman won a primary by 3,200 votes, a margin smaller than the number of mail-in ballots disqualified in that election. In 2018 in Florida, the number of mail ballots tossed was greater than the 10,033 votes that secured one candidate a U.S. Senate seat.

More than 45 million Americans have already returned mail ballots, according to the U.S. Elections Project. That includes nearly 5 million voters in the battlefield states of Texas, Michigan and Pennsylvania, where elections workers will have to verify, process and count ballots in a matter of days.

More than 25 states have taken steps to broaden access to mail voting during the pandemic, including investing in technology and staff.

Some also have created processes for voters to fix signature problems if their ballots are challenged — which should lead to a lower rate of rejection, experts say.

But experts say mail voters are far more likely to be disenfranchised than those who vote in person.

That’s particularly true for young people, who are more likely to experiment with various handwriting styles; the elderly, whose signatures sometimes change with age; people with disabilities; and those voting by mail for the first time — a category that this year includes millions of Americans.

People tasked with verifying signatures often receive little or no instruction. According to one study, those without formal training are more likely to flag a genuine signature as a fake rather than identify false signatures as real.

“It is just ripe for error,” said Linton Mohammed, a forensic document examiner in California who has been an expert witness in lawsuits over ballot signature rules.

Voters whose ballots are rejected aren’t always given the opportunity to correct, or cure, the issue. In states like Mississippi, West Virginia and Wisconsin, ballots aren’t counted until the day of the election, so voters there will have little, if any, time to correct errors.

Voters in Pennsylvania are not guaranteed a chance to fix a perceived signature mismatch. Officials there aren’t allowed to reject ballots on the basis of a signature problem alone, but a signature discrepancy paired with another problem, like a wrong address, could trigger a review.

In Texas, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals recently ruled that officials can exclude mail ballots with signature discrepancies, and do not have to notify voters of the decision until after the election.

Here’s how signature verification works in many states: An election employee scans the barcode on the ballot envelope, which pulls up the voter’s file on a computer screen. That may include a single signature from a driver’s license or voter registration card, or several signatures that the state has collected over time.

The election worker compares the signatures and makes a decision in as little as five seconds.

If the worker determines the signatures match, the ballot moves on to be counted. If not, the ballot is set aside for further review.

In some populous areas, like Los Angeles County and Clark County, Nev., a computer program takes the first pass at ballots, scanning for possible handwriting mismatches. If a discrepancy is found, the signature is given a second, and sometimes third, look by humans.

But in smaller counties with fewer resources, and in states where mail-in voting wasn’t widespread until this year, election workers rely on their own eyes.

In Texas’ Hidalgo County, the process is so low-tech that election workers use a paper clip to attach a copy of each voter’s ballot application to the ballot envelope, so that employees can glance at the two signatures.

In Detroit, employees from across City Hall are being reassigned to process an estimated 200,000 mail-in votes.

“It’s more on-the-job training,” said Gerrid Uzarski, the elections director in Kent County, Mich., home to Grand Rapids. “Someone starts off, someone who’s done this before shows them what they’re looking for.”

A forensic-level analysis isn’t the goal, many election officials said. Instead, workers check to see if signatures look similar enough to be counted, and don’t reflect the wrong name or diverge drastically from the one in the voter’s file.

“We are not real picky as long as it looks similar,” said Jennie Aines, elections director for Franklin County, Pa. She said her staff does not receive any type of instruction in signature analysis.

“There’s no training,” she said. “We are all just office workers trying to get stuff done in here.”

If vote margins are close, the verification signature process could become the “hanging chad” of the election, experts say, as differences in how counties handle the process could open the door to legal challenges.

Until this year, many states did not require elections officials to notify voters of issues or give them a chance to fix them. But a series of court rulings have held almost unanimously that discarding a vote without notice is a violation of a voter’s due process rights.

Rules and timelines for curing signature issues, however, vary widely by state.

Rosalie Weisfeld, a 64-year-old who has voted in every election for the last 30 years, said she was never given the chance to fix her ballot after it was rejected in a McAllen, Texas, election in 2019.

“I truly believe that my voice is heard through my vote,” Weisfeld said. “All it would have taken is a quick phone call to me.”

Without a cure process, rejecting ballots for handwriting issues isn’t fair to voters, said Thomas Vastrick, a forensic document examiner who has taught signature verification classes for Florida election workers.

Vastrick suggests multiple layers of review, including a check by a supervisor with more training and an inspection by a bipartisan panel of elected officials or outside experts.

“We always err on the side of the voter,” said Robert Rodriguez, a spokesman for the Miami-Dade County Elections Department.

Only election workers who have been trained and passed a test are allowed to verify signatures, Rodriguez said. Of the county’s 105 permanent election workers, 80 do verifications. The county is also hiring 2,000 temporary workers to process ballots, some of whom do signature work, Rodriguez said.

Elections workers contact voters with flagged signatures and ask them to fill out an affidavit. Disputed signatures will be sent to county canvassing boards for a final decision — the same group in the national spotlight after the 2000 election that scrutinized hanging chads and other imperfections on discarded ballots.

Signatures that don’t match do not always signal fraud.

In addition to the young and the elderly, voters whose first language is written right to left — such as Arabic or Urdu — are less likely to have a consistent signature in English, experts say.

Medication can also affect one’s handwriting, as can fine motor skills issues, disabilities and injuries.

North Dakota resident Maria Romo didn’t learn until this year that her vote in the 2018 midterm election had been rejected due to a perceived signature mismatch.

Romo said her already messy handwriting has gotten worse since she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Her hands sometimes go numb and she struggles to grip a pen. Sitting down, standing up or resting her arm on a chair can change the look of her writing — all of which she would have told elections officials, she said, had they asked.

“I was surprised to learn that they could just throw the ballot away, and I was wondering why I was never told, or given the chance to explain,” Romo said.

She joined a lawsuit against North Dakota this year that led to a requirement that election officials notify voters of issues with their ballots and give them a chance to fix them.

Emily Will, a forensic document examiner in North Carolina, said she’s troubled by the idea that workers may be comparing ballot signatures to just one, or even a few, samples from the voter’s file. She said she likes to have at least 20 examples of a voter’s past signature when she performs a verification, with several having been written recently.

“Think about signing a credit card receipt as opposed to your will or your mortgage papers,” she said. “Some people might consider their ballot signature very important, but some might think this is just nothing and they just scrawl it out.”

Amy Campbell of Philadelphia said she thinks she signed her ballot correctly in the June primary but election officials canceled her vote, claiming they “could not obtain” her signature.

The 26-year-old, who voted by mail due to concerns of COVID-19, said she was angry that she was not given the chance to cure her ballot.

“I thought I had done what I was supposed to do to vote and make sure I was doing my part to keep my city safe,” Campbell said. “It was frustrating that some minor clerical issue disqualified my vote.”

The interactive questions included in this story are hypothetical ballot scenarios using real matching and non-matching signatures from a variety of sources.

Times staff writers Priya Krishnakumar and Swetha Kannan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.