Shooting of L.A. County deputies new flashpoint in a ‘tinderbox moment’

The video showed a shooting that shocked the conscience: a cold-blooded attempt to kill two Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies at close range in Compton. Immediately, unequivocal condemnations flooded in from law enforcement officials, city leaders and the nation’s most prominent politicians.

President Trump called for the unknown shooter to receive the death penalty. Trump’s opponent in the November presidential election, former Vice President Joe Biden, called for the gunman to face “the full brunt of the law.”

Najee Ali, a longtime South L.A. activist, understood the anger and joined in condemning the shooting. But he also questioned why such swift calls for justice don’t come when it is the police who cause the injuries.

There were police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, which helped spark weeks of demonstrations and unrest around the nation this summer. And Ali also cited several controversial shootings by sheriff’s deputies that have given rise to recent protests.

“I don’t agree with the shooting of anyone that’s unjustified, including deputies but also civilians,” he said Sunday, adding that he plans to join other Black leaders this week to “stand in full solidarity in condemning these actions.”

With the issues of racism, policing and public safety emerging as key issues in the upcoming presidential election, it was little surprise that the attack on the L.A. County deputies immediately became a flashpoint in the roiling debate.

Nothing in policing occurs in a vacuum in 2020 — even incidents that elicit tremendous sympathy for the police, and especially in a troubled agency like the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, where deputies have been accused of running their own gangs and the sheriff has been accused of harassment and mismanagement. It didn’t help when deputies arrested a reporter outside the hospital where the deputies were being treated.

An extended video and radio calls offer a clearer picture of how two Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies sitting in their car Saturday night were shot by a gunman.

Within hours of the shooting, a small group of protesters had gathered there, enraging officials and law enforcement supporters. Across Los Angeles and the nation, the shooting was swiftly transformed into a political talking point, with speculation swirling as to the possible motivation of the gunman — and whether it had anything to do with the anti-police messaging of recent protests.

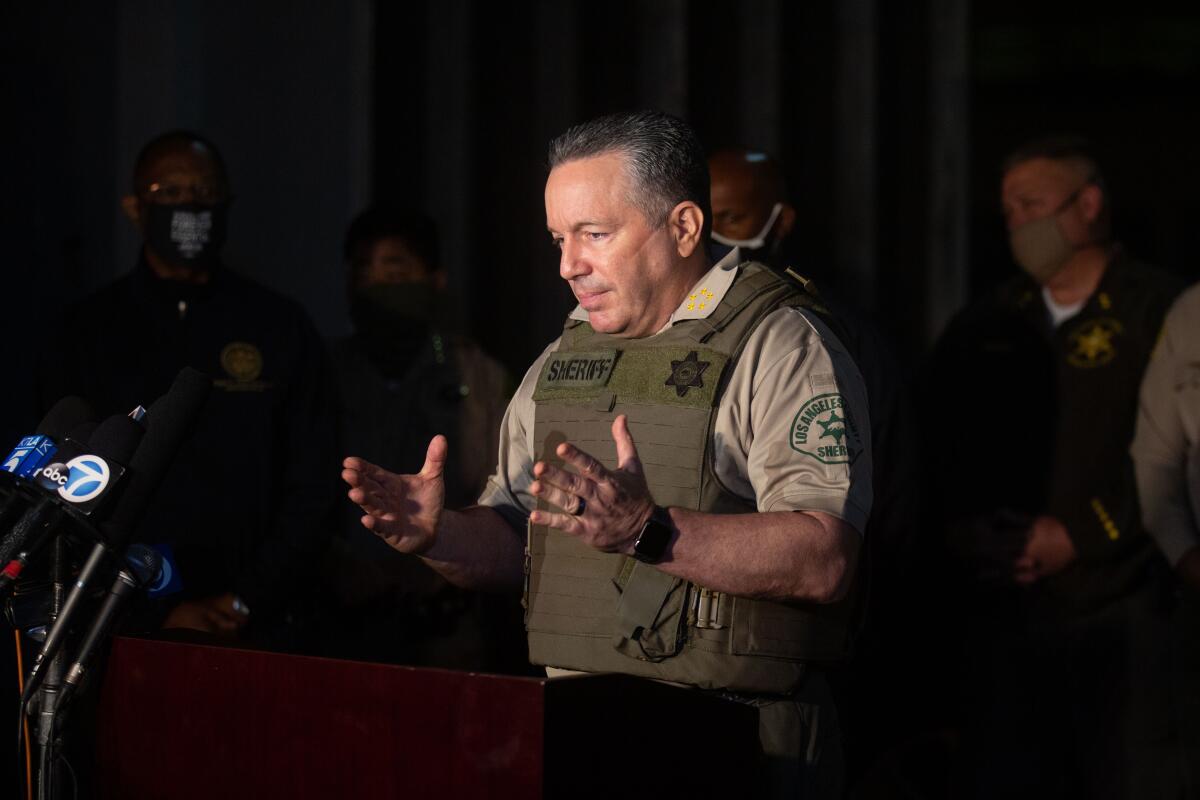

“Words have consequences,” Sheriff Alex Villanueva said, apparently stoking that idea even though his department has not named a suspect or offered any motive for the attack.

Experts said the reactions were unsurprising but worthy of careful consideration, given their potential implications.

According to Dr. Sarah Vinson, a forensic psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry at Morehouse School of Medicine, “all of us have confirmation bias,” and people often contextualize a major event by applying to it their own preexisting ideas about a broader social issue.

That can exacerbate rifts between people in fraught situations. It can also be dangerous, she said, because it can lead to incorrect conclusions — like that a single person deciding to shoot two deputies means people should stop protesting other shootings by law enforcement.

“That’s a really, really important thing to point out, because you absolutely will get people who will spin this into meaning that these protests are causing problems,” Vinson said.

In reality, she said, the protests are a response to the problem, not the cause: “If there wasn’t injustice in the system, they wouldn’t be out in the streets.”

Erin Kerrison, an assistant professor at UC Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare who has studied police officers’ feelings about the job and their perception in the communities they serve, said there is a correlation between officers’ perceptions and how they operate in the street.

The less they feel like the community respects their authority, the more likely they are to use force and to buck department policies, according to her research. And because of that, she worries the shooting of the deputies, in a “tinderbox moment” of growing distrust in institutions, will make officers feel as if they have a “green light” to use more deadly force to protect themselves.

“It’s the precursor to the very behaviors that we as a collective want to put a stop to, which is police violence,” she said. “I foresee some real tensions between on-the-ground officers and on-the-ground folks who question them.”

Chuck Wexler, president of the Police Executive Research Forum, a Washington-based law enforcement think tank that works closely with police agencies nationwide, said that when he learned of what happened to the deputies, he immediately thought back to a similar incident in 2014, when two New York Police Department officers were fatally shot in their vehicle.

At the time, New York had been experiencing intense protests over the police killing of Eric Garner. In the aftermath, the social media accounts of the shooter were picked apart for clues as to his motivations, and some seized on posts in which he referenced Garner and foreshadowed the shooting as proof that he’d been motivated by the broader protest movement.

Many in law enforcement today want to know what motivated the L.A. shooter, too, Wexler said. But they also have broader questions.

At recent protests, the “level of vitriol” toward police is much greater than in past years, and police are worried that will translate into more violence toward officers. This incident didn’t create that fear, but it will exacerbate it, Wexler said.

At the same time, there is growing recognition among police that the preservation of life, which they have always stressed when it comes to their fellow officers, also must be applied to the individuals they are arresting and confronting on the street. In that way, they have some common ground with protesters, he said.

“There’s legitimate concerns that everybody has, on both sides, for the sanctity of human life,” Wexler said. “It used to be that police would say, ‘It’s important that the police officers go home at night.’ In changing the culture, it’s more important that everybody go home safe at night.”

Laura E. Gómez, director of the Critical Race Studies Program at UCLA School of Law, said that when she heard Villanueva say “words have consequences,” it struck her that activists had used similar language after it came out that a white teenager charged with shooting and killing two protesters in Kenosha, Wis., had a history of praising Trump — who has been accused of stoking tensions between police and protesters through his rhetoric.

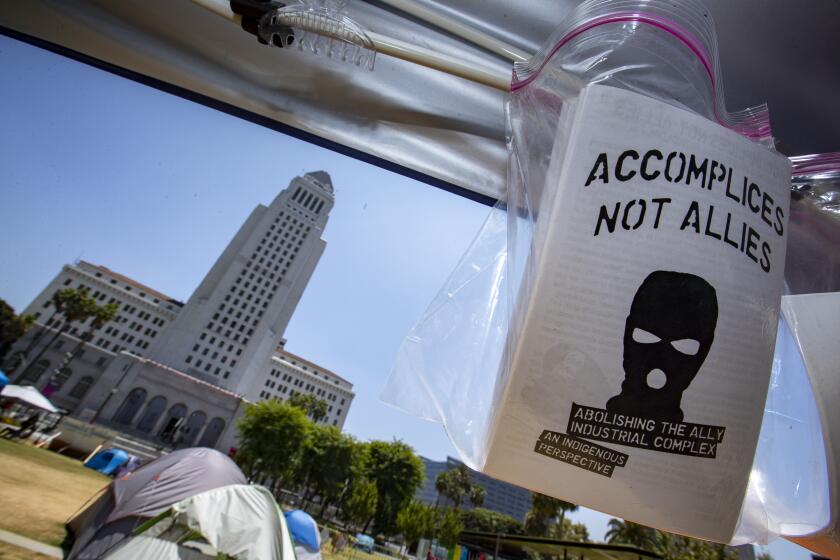

The encampment had been in Grand Park since June. Activists said it was cleared because of ‘misdirected anger’ over the recent shooting of two sheriff’s deputies.

“Since words do matter,” Gómez said, “maybe all of us need to take a breath and consider the context a little bit more before we weigh in to inflame folks, to inflame our allies.”

Ali, the South L.A. activist, said he rejected those who had protested outside the hospital where the deputies were being treated. (At least one protester was heard on video saying, “I hope they … die,” a phrase that was criticized through the day in conservative media and became a trending topic on Twitter.)

But he wonders why there was not more mainstream condemnation in the cases of Andres Guardado, an 18-year-old Latino security guard who was fatally shot by a sheriff’s deputy in June, and Dijon Kizzee, a Black bicyclist who was killed while fleeing deputies last month.

Like the deputies who were shot while sitting in their patrol car, Ali saw Guardado and Kizzee as “innocent targets of an unprovoked shooting,” he said. Both of those shootings are under investigation.

Ali said he would continue to advocate for protesters and the families of those killed by law enforcement officers in the region and to condemn the shooting of the deputies.

There’s no reason why both can’t be done at once, he said — and anyone who suggests otherwise should not have their voices amplified.

“Cooler heads need to prevail and be listened to in this moment of crisis in L.A. County,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.