Hours after shooting of deputies, law enforcement clears L.A. protest encampment

Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies shut down a months-old protest encampment in downtown L.A.’s Grand Park early Sunday in a move that activists criticized as retaliation for recent protests of a deputy-involved shooting.

The encampment first appeared in Grand Park across from City Hall in June amid protests over the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis. It was cleared out around 3 a.m. after deputies declared an unlawful assembly in the area, the Sheriff’s Department said in a statement.

Authorities said the action was taken because of “deteriorating conditions” in the park. They denied it was connected to the shooting of two deputies in Compton late Saturday or recent demonstrations against the department in South L.A. after deputies shot and killed bicyclist Dijon Kizzee. On Friday, deputies in riot gear surrounded a peaceful news conference held by some of the same demonstrators.

Protests near the South L.A. sheriff’s station over Kizzee’s killing have drawn hundreds of demonstrators, including those affiliated with Black Unity L.A., the protest group that had also been running the encampment.

In its statement, the Sheriff’s Department alleged that “illegal narcotic activity, vandalism and graffiti” had become an issue near the encampment. About 25 protesters and 11 homeless people were in the encampment when it was cleared. One person was arrested for trespassing, the Sheriff’s Department said. The park will be closed for an undetermined period of time.

Several activists remained in the area for several hours to protest the dismantling of the encampment. Sean Beckner-Carmitchel, 34, an activist who sometimes livestreams from protest scenes, said deputies blocked him and another reporter at a barricade from getting close enough to film the eviction of the protest site. He stayed near Spring and 1st streets for several hours until, he claims, LAPD officers began chasing him without warning and tackled him to the ground.

“They started grabbing me by the shoulder and sort of violently dragging me across the street — at which point the pain became extreme,” said Beckner-Carmitchel, who told officers that he had a torso injury from an earlier protest.

Beckner-Carmitchel lost consciousness and was later hospitalized. Officer Mike Lopez, an LAPD spokesman, said two protesters were arrested for failing to disperse but could not confirm details of Beckner-Carmitchel’s injuries.

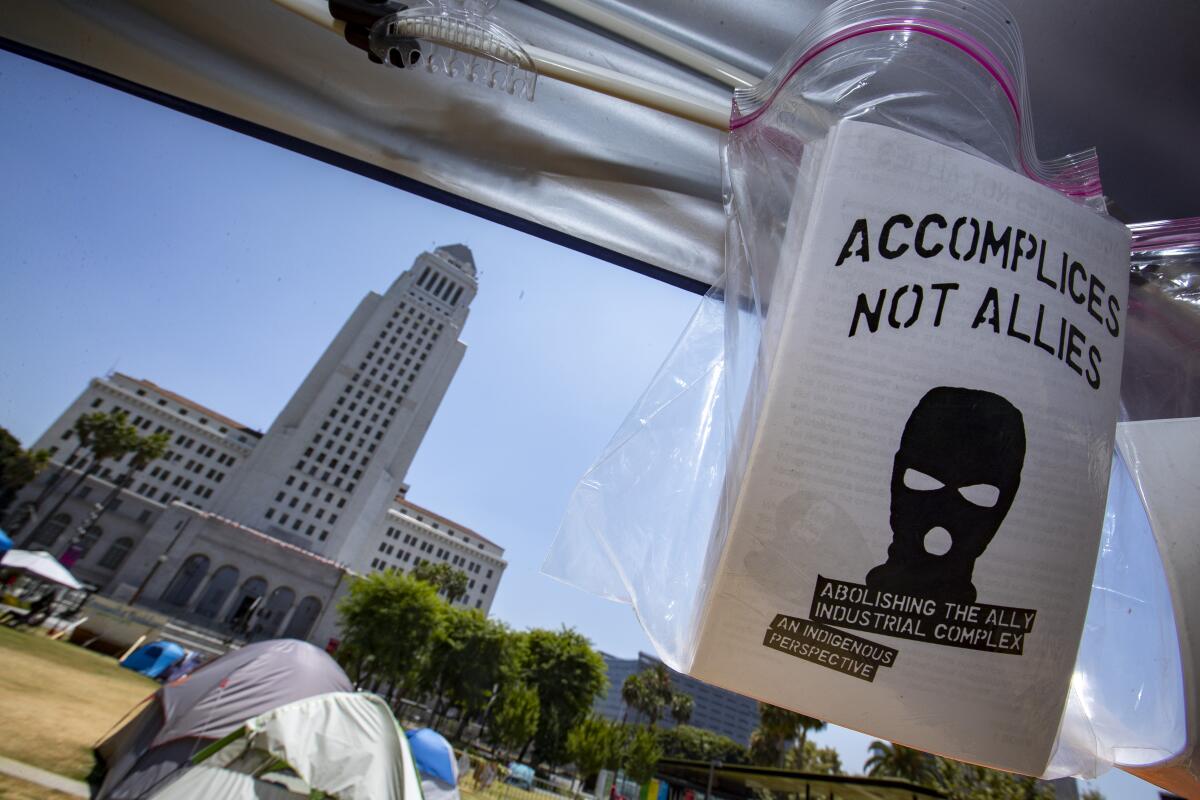

For months, the group had been occupying a fenced-off section of Grand Park, hosting movie nights, training seminars for medical aid during protests and other educational events.

The group’s demands included an end to the practice of qualified immunity for police, which shields officers from civil liability for some of their actions; eliminating the L.A. Unified School District’s campus police; increasing deescalation training for law enforcement; and opening all police discipline records to the public.

In August, organizers with the group said about 30 people were directly involved with the site, with about 15 spending their nights there. The encampment had its own kitchen and a donated library, as well as lounges erected inside the area it had fortified with barricades and wooden palettes. Members could often be seen giving food to nearby homeless people and had also organized visits to skid row to provide services.

The area surrounding the encampment, however, had become increasingly filled with homeless men and women over the summer, and had begun drawing the ire of community leaders. The downtown L.A. Neighborhood Council expressed frustration with the encampment, and some local residents grew worried after Los Angeles police responded to a reported sexual assault in a public restroom near Spring Street earlier this summer.

Around the same time, signs warning that the encampment was illegal were posted near Grand Park at the direction of the Sheriff’s Department.

By late Sunday morning, the park had been fenced off completely. With the exception of a few collapsed tents and remaining garbage, most signs of the encampment had been taken away.

Roxanne McQueen, a Black Unity L.A. activist who has been there for months, said she awoke around 3 a.m. to someone shaking her tent and looked out to find at least 20 deputies in riot gear standing near the entrance to the park.

She said the protesters were given 15 minutes to gather all their belongings before deputies moved in. McQueen said deputies seized anything left behind, which included stores of water and food that Black Unity has shared with nearby homeless men and women in the past, as well as the community library. A Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman did not respond to questions about what was done with belongings or perishables left in the park.

For protesters who had been living in the park since its establishment, the rushed eviction meant they lost virtually all that they owned.

“We have people who have nothing now because they’ve taken it all, either thrown it away or confiscated it,” said a Black Unity L.A. member who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisals from police. “It makes no sense to give people 15 minutes to pack up their life’s belongings, and if they don’t, then you’re going to arrest them. That just seems cruel.”

Roxanne Allen, 29, scoffed at allegations of drug use or poor conditions. She said the encampment had been a positive place that fell victim to “retaliation” from the Sheriff’s Department’s over the protests following Kizzee’s death.

“It was supposed to be a centralized kind of point for everyone to come together and give back to our own community and be there for our own community,” Allen said. “It was retaliation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.