Police reform advocates scrutinize police unions, calling them obstacles to reform

Activists in the growing movement for police reform in the U.S. have for months targeted large police budgets as a central impediment to change, flooding streets and municipal Zoom meetings with demands to “defund the police.”

But for years behind the scenes, other reform advocates have pinpointed another roadblock to progress: police unions and the influence they wield.

Now, two prominent organizations — the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and Campaign Zero — have each launched online campaigns challenging police union contracts in big cities like Los Angeles and state laws that have cemented union-backed protections in California and elsewhere.

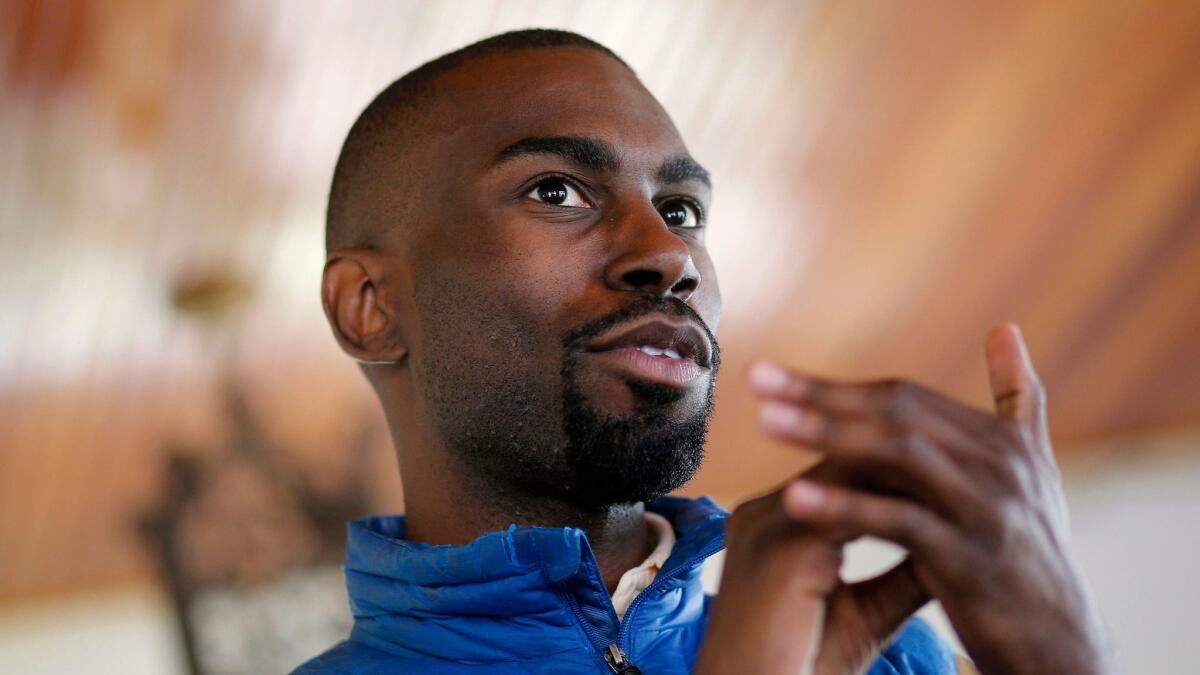

DeRay Mckesson, an activist with Campaign Zero, said his group first began researching police union contracts and Officers Bill of Rights laws in 2015, and quickly came to realize that they are “one of the key levers that block the transformative change that people have demanded.”

In many cities, the big budget cuts sought by defund activists will only be possible if union contracts that control staffing levels and other personnel decisions — which constitute the bulk of police budgets — are discarded, Mckesson said.

His hope is the new campaign will encourage more community activists across the country to study police union provisions in their own cities and push elected officials to revisit the ones that block reform whenever the contracts are next negotiated.

NAACP LDF President Sherrilyn Ifill, in her own statement challenging police unions last week, said her organization supports due process protections for public employees but not contracts that bolster “a regime of impunity” for cops who are guilty of misconduct.

“Understanding how police officers are shielded from accountability for misconduct requires an examination of police union contracts, which often contain provisions that preclude the prompt and thorough investigation of unconstitutional police misconduct,” Ifill said.

Police unions and their collective bargaining agreements with cities have long shaped policing policy, with elected officials under pressure to provide public safety and keen on securing police endorsements agreeing in the past to wide-ranging provisions that limit how, when and whether officers can be investigated and disciplined.

The new campaigns by LDF and Campaign Zero reflect a growing frustration among activists with that influence. They also follow widespread protests across the country over police brutality, and a recent poll that found a majority of Californians — 61% — favored limiting the power of police unions by reducing their collective bargaining rights.

Even with budget cuts, police spending in Los Angeles will reach about $3 billion a year. How did the LAPD come to consume to much of the city’s ‘unrestricted’ money?

Both LDF and Campaign Zero raised concerns about policies that limit the time frame under which misconduct investigations can occur, arguing they can block officers who are guilty of misconduct from being held accountable. In Los Angeles, that limit for LAPD officers is one year.

The groups also raised concerns about policies that prevent city officials and police leaders from firing certain officers who have been found guilty of misconduct. In Los Angeles, LAPD Chief Michel Moore recently expressed frustration with his inability to fire officers who disciplinary boards allowed to remain on the force.

L.A.’s contract with the union that represents LAPD officers — which dismissed the latest critiques as misguided — is in force until summer 2022.

Campaign Zero, which has dubbed its new campaign “Nix The Six” for the six union influences it says should be dismantled, has collected and posted hundreds of union contracts from across the country, analyzing them for common provisions that they believe block accountability.

Often, those contracts were implemented with little input from the community members who are most impacted by police misconduct, said Sam Sinyangwe, Mckesson’s partner at Campaign Zero.

“Nix The Six is about directly taking on the power of the police unions and holding them accountable for the many ways in which they have sort of rigged the system in favor of officers who have committed misconduct,” Sinyangwe said.

The campaign criticizes Bill of Rights laws for blocking transparency, police union influence in politics and the negotiation of union contracts without public input. It challenges the destruction of disciplinary records by some departments, as well as rules that delay or restrict interrogations of officers who have been accused of misconduct.

It also challenges the idea that taxpayers should foot the bill for officer misconduct when municipalities are sued for it.

The Nix The Six effort follows another by Campaign Zero, known as “Eight Can’t Wait,” which encouraged jurisdictions to implement eight policy changes to reduce the use of force by officers, among other things. That campaign helped shift policy nationwide and in Los Angeles, where the L.A. Board of Police Commissioners recently adopted a new use of force policy with some of the provisions the Campaign Zero initiative recommended.

The Police Commission said it continues to consider policy proposals from reform organizations, including about union influence.

“There are many excellent reform ideas that are being proposed by national and local organizations,” the board said in a statement to The Times. “The Board, with the assistance of its newly instituted advisory board, is evaluating all current reform proposals for potential implementation.”

It said the composition of disciplinary boards is one issue currently under review.

Josh Rubenstein, an LAPD spokesman, said the department follows state laws regarding discipline.

The board of the Los Angeles Police Protective League, the union that represents rank-and-file LAPD officers, said the LAPD is a “national model when it comes to police officer accountability,” and the league “is a partner in building and improving that model.”

It challenged whether certain provisions should be changed, including the time limit on investigations into misconduct, saying there are statutes of limitation for all crimes and “the administrative system is no different.” It backed the current model, under which a panel of civilians mete out final discipline for guilty officers, not Moore, calling it a progressive model.

The league also dismissed the “Nix The Six” platform as “a poorly disguised attack on organized labor,” saying it targets standard provisions used in union contracts for all sorts of public employees, not just police.

“If they were truly interested in improving police and community outcomes, they would be joining us in our push for increased training on issues such as crisis intervention and implicit bias and hiring the most qualified officers,” the league’s board said in a statement. “The fact that they’re not advocating for those initiatives is telling.”

Campaign Zero has also taken heat of late from community organizations that back the defunding of police, who say the group’s focused reforms are distractions that help officials avoid more substantive changes.

Mckesson and Sinyangwe said the reforms they’ve helped drive forward have made police more accountable, and hope the new campaign will do the same.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.